Kilauea, a volcano on the Big Island of Hawaii, has been erupting for more than 22 years. That marathon eruption is just one of the features that make this tropical peak stand out in the volcanic crowd. Kilauea’s lavas, which often wend their way to the sea, where they create towering plumes of steam are richer in iron than those from most other volcanoes. Also, Kilauea’s locale is odd. The majority of volcanoes lie near an edge of one of Earth’s tectonic plates, but Kilauea sits far out in the North Pacific, more than 3,000 kilometers from the nearest plate boundary.

There are geographical idiosyncrasies all around Kilauea too. It shares the Big Island with four other volcanoes, only one of which is considered active. Other islands and submerged seamounts in the Hawaiian archipelago, all formed by volcanoes long dormant or extinct, stretch in a tight line toward the northwest for 3,500 km. There, the single file of seamounts makes a 60° dogleg to the north. The farther the islands and seamounts are from Kilauea, the older their rocks.

The apparent chronology of this picket fence of volcanoes and seamounts, along with evidence culled from the chemistry of their respective lavas, led some scientists decades ago to speculate that the islands were formed as the ocean crust supporting them inched northwest over an abnormally hot spot in Earth’s mantle.

As these geologists saw it, that hot spot, now under Kilauea, is generated by an upwelling zone of hot rock, called a mantle plume, that intermittently pierces Earth’s crust blowtorch style. When that happens, new volcanoes form. As the mobile crust carries active volcanoes away from the underlying plume’s largely stationary source of molten rock, or magma, the volcanic features fall dormant. Meanwhile, the moving tectonic plate brings a previously unaffected area of crust atop the plume, and a fresh zone of volcanic activity springs forth there to build new islands.

Because hot spots lie deep within Earth, researchers who developed the mantle-plume hypothesis had a tough time convincing skeptical colleagues. To be sure, plumes may not explain every volcanic island and seamount (see “Bend and Stretch,” below). Now, however, researchers are performing sophisticated analyses of seismic waves that have traveled deep within the mantle beneath Hawaii as well as within some other volcanically active regions. The result is strong evidence that plumes are major actors in sculpting Earth’s volcanoes.

Detailed mathematical models of how magma might flow deep within Earth suggest that plumes can take many shapes, not just the mushroom blobs that most researchers had envisioned. Also, the simulations show that zones of plume material that have distinct chemical compositions can remain intact during their long, slow journey to Earth’s surface—a finding bolstered by recent analyses of lavas that have erupted from Hawaiian volcanoes during the past 3 million years.

Deep down

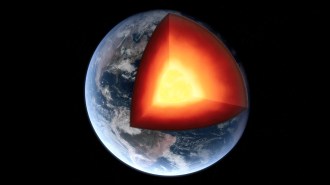

Most of our planet’s 1,500-or-so active volcanoes are located near subduction zones, where one of Earth’s tectonic plates scrapes beneath another and heads down into the upper layer of the mantle. That layer, where molten rock slowly oozes under pressures millions of times as great as those exerted by the atmosphere at sea level, lies just beneath Earth’s 5-to-70-km-thick crust. When the subducting slab reaches a depth of several dozen kilometers, some of its constituents melt, expand to become less dense, and then percolate through cracks or other weaknesses in the overlying slab of crust. When that molten rock pierces the surface, voilà, a volcano erupts.

Volcanoes from mantle plumes develop differently than their subduction-zone brethren do. Instead of rising from the upper reaches of the mantle, the molten rock that fuels them comes from the boundary between Earth’s mantle and the layer of molten iron that lies beneath it. This boundary sits at a depth of about 2,900 km—approximately the distance between New York and Denver.

Convection in the mantle slowly transports to Earth’s surface immense amounts of heat from the core, which may measure up to 5,000°C. Think of a spherical, planetsize lava lamp with its heat source at the center.

As magma in the lower mantle warms, its properties change, says Scott D. King, a geophysicist at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind. The material expands, becoming less dense, and flows more readily.

Buoyant plumes of hotter-than-average material rise through the mantle at speeds of just a few centimeters per year. When a plume reaches the ceiling formed by Earth’s crust, it becomes a hot spot and fuels volcanic activity.

The density difference between a rising mantle plume and the cooler material that surrounds it enables scientists to distinguish the two. For instance, seismic waves slow down when they travel through low-density rocks, says Raffaella Montelli, a geophysicist at Princeton University. She and her colleagues use the vibrations spawned by large earthquakes to probe Earth’s interior, much the way doctors use ultrasound to investigate a patient’s inner tissues.

By analyzing patterns of seismic waves that travel through rock as pressure pulses, which seismologists call P-waves, Montelli’s group identified 32 broad regions in the mantle worldwide where seismic waves travel more slowly than average. The scientists concluded that these zones of low-density magma are mantle plumes.

Six of those regions—those that lie beneath Ascension Island in the South Atlantic, the Azores and Canary Islands in the North Atlantic, and Easter Island, Tahiti, and Samoa in the Pacific—clearly extend all the way to the core-mantle boundary. P-wave-based images of other alleged plumes, such as those beneath Cook Island in the Pacific, the island of Kerguelen in the Indian Ocean, and the Cape Verde Islands in the Atlantic, become fuzzier with increasing depth.

Geologists then turned to S-waves—a type of seismic vibration that travels more slowly and transmits shear forces through rocks. The analyses revealed that those plumes also extend to the core-mantle boundary, Montelli reported last December in San Francisco at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

The gallery of seismic wave–based mantle images suggests, surprisingly, that some individual plumes fuel volcanic activity at several locales on Earth’s surface, says Montelli. An offshoot of the plume that purportedly created Ascension Island long ago also stoked volcanoes on the island of St. Helena—where Napoleon spent 6 years in exile—about 1,200 km to the southeast. Similarly, the plumes that now fuel volcanic activity in the Azores and the Canary Islands—archipelagoes in the North Atlantic that lie about 1,600 km apart—apparently branch from a single trunk at a mantle depth of 1,450 km.

In several regions, such as south of the Indonesian island of Java or in the Coral Sea northeast of Australia, P-wave and S-wave images show broad, plumelike features rising from the base of the mantle but extending only halfway to Earth’s surface. These features may be hot spots in the making, subterranean harbingers of volcanoes yet to be, says Montelli.

Hard evidence

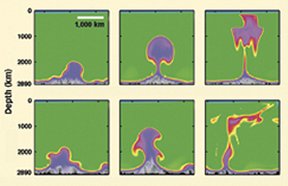

In the 1960s, scientists first conceived of mantle plumes as long cylinders of buoyant rock that gradually flatten and spread into mushroom shapes as the molten masses rise through the mantle. However, new computer simulations suggest that plumes can take on a variety of contours.

In most previous models of mantle plumes, the molten rock’s viscosity and buoyancy depended only on changes in temperature, says Cinzia G. Farnetani of the Paris Geophysical Institute. But she and her colleague Henri Samuel of Yale University recently developed a model that also adjusts a plume’s density according to its chemical composition. That’s important because as plumes rise through the mantle, the pressure around them decreases. The plume’s minerals can then crystallize. This changes the molten mixture’s density and viscosity, releasing or absorbing heat in the process.

In their simulation of an ocean basin–size chunk of Earth’s mantle, Farnetani and Samuel tracked the motion of plumes rising beneath a tectonic plate that slogged along at a velocity of 6 centimeters per year. In some cases, large regions of molten rock at the base of their simulated mantle formed 600-km-wide blobs that bubbled up to the overlying tectonic plate, where they proceeded to melt holes in the crust and trigger massive volcanic activity.

In other cases, the simulated plume’s buoyancy wasn’t strong enough to overcome the mineralogical changes that took place inside the plume as the molten rock ascended. So, much of the plume stalled in the middle layers of the mantle, and the small finger that eventually ascended to the crust was narrow and created only a weak hot spot. The researchers describe their findings in the April 16 Geophysical Research Letters.

Previously, scientists had speculated that the inner zone of a plume consists of molten rock from the lowermost mantle and that the outer layers include material dragged along from higher mantle regions as the plume ascended. This could explain how plume-fueled volcanoes located near one another could spew lavas with different chemical compositions.

But results of simulations using Farnetani and Samuel’s new model suggest that such differences can instead arise because of chemical heterogeneities in the broad mass of material bubbling up from the base of the mantle. Individual globs of viscous material swept into the plume at these lower depths would stretch upward like pulled taffy as the plume rises but wouldn’t mix with neighboring globs, says Farnetani.

Samples of old and new lava recently drilled from Hawaiian volcanoes offer real-world examples of magma streams within plumes that didn’t mix as they rose to Earth’s surface. Two to 3 million years ago, the Hawaiian hot spot began fueling two closely spaced but parallel chains of volcanoes, which scientists have dubbed the Kea and the Loa chains.

High-precision analyses have now shown that the two chains of volcanoes spew not chemically similar lavas but rather, lavas with significantly different ratios of various lead isotopes, says Mark D. Feigenson, a geologist at Rutgers University in Piscataway, N.J. That suggests that the Loa and Kea chains of volcanoes are venting material that originated in different chunks of the lower mantle.

Within each individual chain of volcanoes, however, the isotope ratios in the lava remain remarkably consistent through time. For example, the ratios of lead isotopes and those of neodymium isotopes for lavas emitted by Mauna Kea 300,000 years ago are indistinguishable from those flowing from Kilauea today, Feigenson and his colleagues report in the April 14 Nature.

That makes sense, Feigenson notes, because 300,000 years ago Mauna Kea was directly above the same hot spot that now underlies Kilauea. In the intervening era, motion of the Pacific tectonic plate carried Mauna Kea about 65 km to the northwest.

Farnetani says that these results are “very exciting” and that they confirm that the mantle-plume models that she and Samuel have developed reflect the conditions recorded in modern and ancient lavas.

Together, she notes, the plume models, lava chemistry, and seismic images that show the large zones of buoyant rock underlying many volcanic provinces are “convincing people now more than ever that mantle plumes indeed exist.”

Bend and Stretch

Mantle plumes may not have created all Pacific seamounts

The Pacific tectonic plate lies over the hot spot that fuels the volcanic activity that formed—and is still forming—the Hawaiian Islands. That plate moves slowly but steadily toward the northwest in a motion chronicled by the 3,500-kilometer-long line of islands and the dozens of submerged seamounts northwest of Hawaii. But at a point about halfway to Japan, there’s a 60° bend in the chain of seamounts, and the line of the even older seamounts points toward the east coast of Russia. This orientation indicates that the Pacific plate previously moved almost directly north.

The ages of rock samples collected from seamounts located near that kink suggest that the plate suddenly veered onto its current path about 47 million years ago.

Several seamount chains in the South Pacific are roughly parallel to the Hawaiian chain of seamounts, and they, too, show 60° bends. Because these South Pacific chains, as their Hawaiian counterparts do, lie on the Pacific tectonic plate, many scientists have speculated that underlying hot spots created all these seamounts. However, analyses of ancient lava samples dredged from undersea peaks cast doubt on that theory, says Hubert Staudigel, a geophysicist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, Calif.

Staudigel and his colleague Anthony A.P. Koppers used the ratio of two argon isotopes in the samples to estimate the age of rocks in two lines of South Pacific seamounts. The ocean crust beneath the Gilbert Ridge and Tokelau seamounts, which lie northeast of Australia, is about 100 million years old. In contrast, the volcanic peaks that lie at the corner of the bend in the Gilbert Ridge chain are about 67 million years old, and those near the kink in the Tokelau line were formed about 57 million years ago.

Neither of those ages matches the 47-million-year age for the bend in the Hawaiian seamount trail—a sign that a sudden swerve by the Pacific tectonic plate didn’t simultaneously cause the bends in the Hawaiian and South Pacific chains, says Staudigel.

What’s more, it’s unlikely that moving hot spots caused the two South Pacific seamount trails. Ages of lava samples from the Gilbert Ridge seamounts suggest that the underlying plume would have had to move through the viscous mantle at the unheard-of rate of 13 centimeters per year, as compared to the 1 cm per year estimated for the plume beneath the Hawaiian chain.

Also, the plumes, which lie just a few hundred kilometers apart, would have had to move in synchrony for millions of years but then decelerate and lose steam at different times. That’s improbable, says Staudigel.

Instead, he and Koppers speculated in the Feb. 11 Science that forces pulling on the southwestern portion of the Pacific tectonic plate might have stretched the ocean crust thin there, creating weak spots that were susceptible to volcanism.

Staudigel admits that there isn’t much evidence to support any specific theory about how the Gilbert Ridge and Tokelau seamounts formed. However, he notes, “the value of this research is … to show that mantle plumes aren’t the explanation.”