Year in review: Zika virus devastates Brazil and spreads fear across Americas

The virus, little-known until this year, led to an upsurge in birth defects in Brazil

ZIKA'S INFLUENCE A young woman holds her daughter, born with microcephaly, outside their home in Recife, Brazil. Researchers this year linked the upsurge in microcephaly cases in Brazil to the mosquito-borne Zika virus.

Felipe Dana/AP Photo

![]() A Brazilian mother cradles her baby girl under a bruised purple sky. The baby’s face is scrunched up, mouth open wide — like any other crying child. But her head is smaller than normal, as if her skull has collapsed above her eyebrows.

A Brazilian mother cradles her baby girl under a bruised purple sky. The baby’s face is scrunched up, mouth open wide — like any other crying child. But her head is smaller than normal, as if her skull has collapsed above her eyebrows.

A week earlier, not far away, a doctor wrapped a measuring tape around the forehead of a 1-month-old boy, held in the arms of his grandmother. This baby too has a shrunken head, a birth defect whose name — microcephaly — has now become seared into the public consciousness.

These images and many more told a harrowing story that case reports alone couldn’t convey: A little-known mosquito-borne virus called Zika appeared to be taking a terrible toll on women and babies, and their families. The world got a gut-wrenching view of microcephaly in 2016, along with a mountain of evidence convincing scientists that Zika bears much of the blame for the dramatic increase in cases.

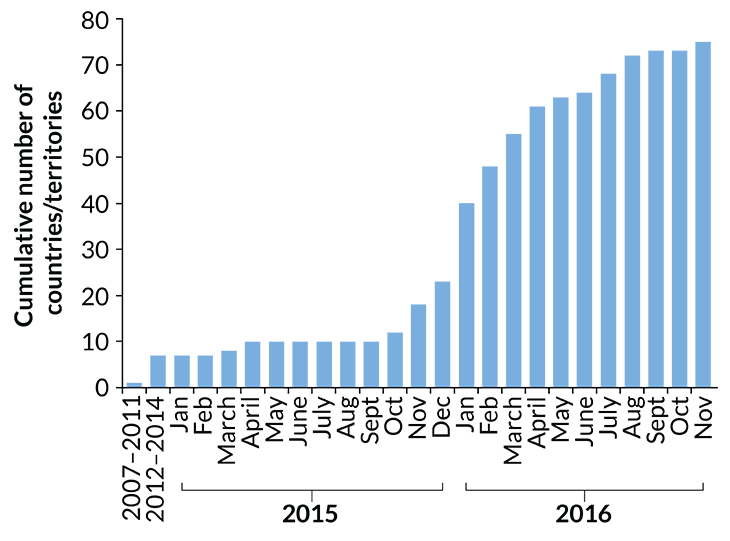

“Once you’ve seen those pictures from Brazil, you realize what a huge impact this kind of outbreak can have,” says Sonja Rasmussen, a pediatrician at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. Brazil logged its first cases of Zika in 2015, but infections there peaked this spring with perhaps up to 8,000 new infections per week. The virus crept northward and infiltrated many more countries including Panama, Haiti and Mexico. Now, the threat has come to the United States: Cases have been reported in every state except Alaska. They stem mostly from travelers infected abroad, but the virus has staked out new territory in Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa and Florida.

As of December 1, Puerto Rico had reported more than 34,000 people with Zika infections. More than 2,700 are pregnant women. And elsewhere in the United States, the CDC has reported well over 4,000 laboratory-confirmed cases of Zika. In these places and others, the images from Brazil have filled expectant mothers (and anyone considering having kids) with uncertainty and fear. “It’s really scary to be pregnant right now,” Rasmussen says. “We don’t know what to tell women.”

The threat to unborn babies wasn’t clear when Zika first hit Brazil, or in earlier, smaller outbreaks on Yap Island in the western Pacific and in French Polynesia. In fact, before 2016, not much was known about the virus at all. The majority of people infected don’t show any symptoms. But in the last year, scientists have thrown themselves at Zika, publishing more than 1,500 papers on different facets of the virus, from what species of mosquito it hides in to what cells it invades.

“We’re learning something new every day,” says obstetrician/gynecologist Catherine Spong, deputy director of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development in Bethesda, Md.

The studies have scrubbed away some of Zika’s mystery — in particular, what the virus does in the womb. Scientists have found traces of Zika in the brains of human fetuses and confirmed that the virus can infect and kill brain cells in the lab. “This is the year that people became convinced that this mosquito-borne virus could cause birth defects,” Rasmussen says.

Though there was no smoking gun — no single piece of evidence that clinched Zika as the culprit — little clues began adding up, beginning with the conspicuous timing of Brazil’s microcephaly upsurge (SN: 4/2/16, p. 26). In January the CDC first issued a warning to pregnant women to postpone travel to Zika-affected regions. On April 13, a day that may be forever etched into Rasmussen’s memory, she and colleagues reported “a causal relationship” between Zika and microcephaly, along with other birth defects, in a study published online in the New England Journal of Medicine. Since then, Rasmussen says, “The data have become absolutely overwhelming.”

In May, a mouse study offered the first direct proof in animals that in utero Zika infection can lead to microcephaly (SN Online: 5/11/16). In September, researchers reported that a pregnant pigtailed macaque infected with Zika in the third trimester then gave birth to a baby whose brain had stopped growing. In human babies, the range of disorders linked to Zika has ballooned to include problems with the eyes, ears and joints, as well as seizures and extreme irritability (SN: 10/29/16, p. 14). At a workshop in North Bethesda, Md., this fall, a room crowded with doctors and scientists watched videos of inconsolable infants jerking erratically, arms and legs unnaturally stiff. “Heartbreaking,” Rasmussen says.

In December, researchers reported a surge in babies with microcephaly in Colombia (SN Online: 12/9/16), further evidence for Zika’s role in birth defects.

Zika isn’t the first virus to harm babies in the womb. Cytomegalovirus can also cause microcephaly, for example, and rubella, known as “German measles,” can leave babies with hearing, vision and heart problems. Even among these viruses, though, Zika stands out. “It’s such a precedent-setting thing,” Rasmussen says. “Never before has there been a mosquito-borne virus known to cause birth defects.”

Despite what scientists have learned in 2016, there’s little consolation for families already affected by microcephaly. And huge questions remain for expectant mothers. In particular, says Spong, it’s not clear just how risky Zika infection during pregnancy really is. One study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in July estimated that the risk of bearing a child with microcephaly increases to somewhere between 1 and 13 percent for women infected in their first trimester.

Spong hopes that a new study will clarify things. It’s called the Zika in Infants and Pregnancy Cohort Study, or ZIP, and the plan is to enroll 10,000 women in their first trimester. They’ll come from Puerto Rico, as well as Brazil and other countries, Spong says, and include both infected and uninfected women.

Tracking these women through pregnancy, birth and their baby’s first year of life could fill in some answers, like whether an infected pregnant woman who doesn’t have symptoms is better off than one who does. It’s also possible that some type of cofactor, like environmental toxins or other infections, is working with Zika to cause birth defects.

“You’re supposed to avoid stress when you’re pregnant,” Rasmussen says. “How do you avoid stress when you’re thinking that your baby could have these problems related to Zika?”

In the best-case scenario, a Zika vaccine could still be a few years away. And though infection rates may be winding down in some places, in areas with seasonally high temperatures and rainfall, such as Puerto Rico, Zika could become a local fixture. Still, any scrap of new information might help. Results from ZIP and other studies won’t erase the damage, but they could offer a pinprick of light following a year darkened by disease.