Better Labeling of Major Food Allergens

One in 25 people—roughly 11 million U.S. residents—suffers from food allergies, according to a telephone survey reported earlier this year at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology annual meeting. In affected individuals, ingestion or contact with certain foods can trigger a potentially life-threatening reaction. However, avoiding the proteins, or allergens, typically responsible for food allergies and other reactions has proven a challenge because food labels often disguise ingredients’ presence, often identifying them only by a chemical name that’s unfamiliar to most people.

Currently, there’s no federal or state requirement that product labels address food allergies. However, Congress has stepped in to remedy the situation.

On July 15, the House of Representatives passed a bill intended to reduce consumers’ confusion over which goods contain proteins from the eight most common foods causing allergies: milk, egg, finfish, shellfish, tree nuts (such as almonds, pecans, and walnuts), wheat, peanuts (a legume), and soybeans. The Senate already passed the bill, S-741, on Feb. 18. Having cleared both houses of Congress, the legislation now needs only the President’s signature to become law. That’s expected to happen soon.

The Congressional Budget Office anticipates that implementing the plain-English food-labeling provisions of the pending law would cost the federal government an estimated $50 million over the next 5 years. Of that, perhaps $41 million would fund Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) studies of the prevalence of food allergies, the incidence of life-threatening allergic reactions, treatments available, and prevention strategies.

The bill doesn’t cover alcoholic beverages, but the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, which was mainly responsible for the bill in the House, has told the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau that it “expects” the bureau to require alcohol labeling to include major food allergens.

Whey to go

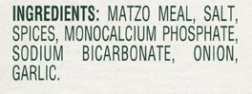

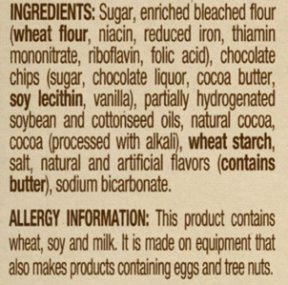

The new food-labeling rules would mandate that products containing or likely to contain allergens from any of the eight potentially dangerous food groups list those allergy sources in “plain English,” as approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Congress has offered FDA two approaches. If a product contained semolina, whey, and natural peanut flavorings, for instance, its label could list the product as having “wheat, milk, and peanuts.” Alternatively, it could list its ingredients as “semolina (wheat), whey (milk), and natural flavorings (peanut).” In cases in which two or more products from the same allergen category occur—for example whey and casein, which is milk protein—only one need be identified as coming from a given allergy-causing food group.

Congress expects the new rules to go into effect for foods entering the marketplace by Jan. 1, 2006. The new law would also instruct FDA to extend the new rules to foods currently exempted from labeling laws—specifically, spices, flavorings, and incidental additives.

The pending law would also require the Department of Health and Human Services, FDA’s parent agency, to investigate the extent to which foods become unintentionally tainted with food allergens during manufacturing. The department would also have to inspect food manufacturing, processing, and packing plants to ensure that allergen contamination is being kept to a minimum.

Finally, the new bill calls for federal guidelines to help restaurants, bakeries, delis, and other food-preparation facilities offer “allergenfree” foods. The rules would describe, for instance, how a restaurant could qualify to advertise gluten-free foods. Gluten is a protein in wheat, barley, rye, and oats that can trigger a serious immune reaction in people with celiac disease (see On Wheat and Weaning).

The new bill notes that there may be products that contain such highly refined elements of a listed item—such as peanuts—that its allergens are eliminated. That’s certainly true for most refined, bleached, and deodorized oils. As such, they wouldn’t have to identify peanuts as their source under the pending law. The legislation would also exempt from allergen labeling, any products backed by scientific data showing that ingestion won’t cause an allergic response—presumably because the original food’s allergens have been altered or otherwise detoxified.

Bill wins broad support

Each year 29,000 people in the United States are hospitalized—and 150 die—from food allergies, according to the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a food-safety group. The bill closes “a major loophole” that now lets ingredients in natural flavorings, natural colorings, and spices go undisclosed, the group notes.

“Under this law, the industry will provide consumers with clear, easily understandable alerts to the eight foods that account for 90 percent of all allergic reactions,” notes Tim Hammonds, president of the Food Marketing Institute, which represents food retailers and wholesalers. “Since there are no cures for food allergens,” he says, “the only effective measure is to help susceptible consumers avoid such foods in the first place.”

John R. Cady, president of the National Food Processors Association, notes that a coalition of industry groups worked closely on this bill, and “urged its passage.”

“Individuals with food allergies or celiac disease must navigate a minefield every time they eat,” notes Rep. Nita Lowey (D–N.Y.). “One mislabeled or unclear item could lead to illness or even death.” Because labels are often incomplete and have often been “written for scientists instead of consumers,” she says, many people suffer needless life-threatening exposures. Even young children with milk allergy, she notes, have had to learn to recognize whey, casein, and lactoglobulin as terms on current food labels for milk or milk derivatives.

“Children shouldn’t have to be scientists to determine if a product is safe for them; there is too much at stake to expect a child to crack a code with everything they eat,” said Lowey. With the passage of this bill, she says, they no longer will have to.

As helpful as the new labeling will be, it offers far-from-foolproof protection from exposure to dangerous food allergens—even in people who are super-vigilant.

For instance, different plants sometimes make proteins so similar to each other that an allergy to one will trigger a reaction to the other. In one reported study, women in India who were allergic to chickpeas—legumes—developed life-threatening allergic reactions when they ate fenugreek, a spice made from seeds of another legume (see The Mango That Thought it Was Poison Ivy). Also, people are sometimes exposed to allergens in the most indirect ways. One can unwittingly inhale allergens from foods being cooked a room or more away (see A Whiff, a Sniff—Then Asthma). And then there are those problematic pecks on the cheek. People with peanut allergy have developed wheezing and hives—sometimes requiring emergency room visits—after being kissed by people who had eaten nuts up to several hours earlier (SN: 7/20/02, p. 40: A Rash of Kisses).