INTO THE DARK AGAIN This composite image shows the eclipsed sun on August 21, 2017, the last total solar eclipse. The faint disk of the moon is visible in the center, and the pale wisps of the solar corona surround it. On July 2, scientists will observe another eclipse over parts of South America.

Solar Wind Sherpas project, P. Horálek, ESO

Two years ago, scientists towed telescopes and other equipment into fields and up mountains across the United States for a celestial spectacle: the 2017 Great American Eclipse.

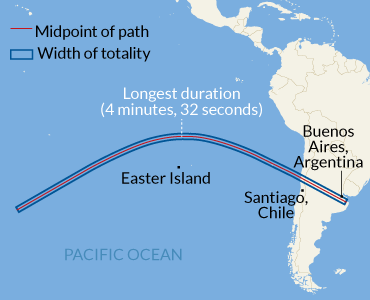

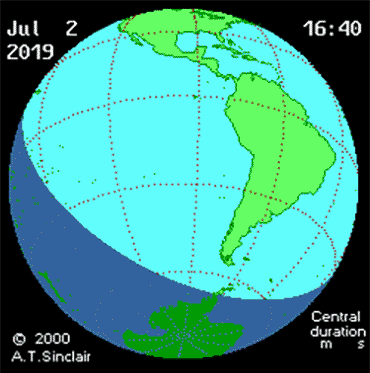

Now, they’re at it again. On July 2, the next total solar eclipse will be visible shortly before sunset from the Pacific Ocean and parts of Chile and Argentina.

Eclipse watchers hope to study some of the same solar mysteries as last time, including the nature of our star’s magnetic field and how heat moves through the sun’s wispy outer atmosphere, known as the corona (SN Online: 8/11/17). But every eclipse is different, and this year’s event offers its own unique opportunities and challenges.

“There are all sorts of outside things you have to be lucky about” in watching an eclipse, says astronomer Jay Pasachoff of Williams College in Williamstown, Mass., who will be near La Higuera, Chile, to view his 35th total solar eclipse. Here are some of the challenges, and potential rewards, facing astronomers.

1. The sun is in a period of low solar activity.

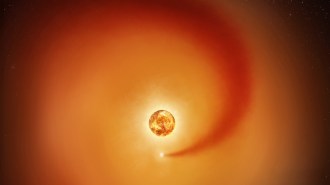

One of the main reasons, scientifically speaking, to observe a total solar eclipse is to catch a glimpse of the corona, whose wisps and tendrils of plasma are visible only when the sun’s bright disk is blocked. This region could hold the key to predicting the sun’s volatile outbursts, including giant burps of plasma called coronal mass ejections that can wreak havoc with satellites and power grids if they hit Earth (SN Online: 4/9/12). But the corona is one of the least well-understood parts of our nearest star.

Still, “some of the science we can do is contingent on what’s happening on the sun at that particular time,” says solar physicist Paul Bryans of the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo.

In every eclipse, the corona looks different, thanks partly to the sun’s 11-year magnetic activity cycle. Magnetic fields in the corona guide the motions of its wisps and whorls, and determine when the sun gives off more powerful bursts like flares or the mass ejections. Scientists have never measured the corona’s magnetic fields directly (SN Online: 8/16/17), but they keep trying.

In 2017, the sun was in a period of low magnetic activity (SN Online: 8/19/17), showing a pitiful number of sunspots, flares and coronal mass ejections. This year, it’s even quieter. “We are in the minimum of the sunspot cycle,” Pasachoff says. “If you look at an image of the sun today, it’s entirely blank.”

That’s both lucky and unlucky. Low solar activity means certain features in the corona, such as plasma plumes that stream away from the sun’s poles, will be more visible now than when the sun is more active. Catching a glimpse of those magnetically controlled plumes could give relatively rare insights into how the corona behaves.

But low activity also means that scientists are less likely to catch a fleeing coronal mass ejection, like those detected by Adalbert Ding of the Institute for Optics and Atomic Physics in Berlin and colleagues in 2015 and 2017 (SN Online: 5/29/18).

Although such an eruption is unlikely, it’s not impossible. The sun “does produce explosive events during this quiet phase,” Bryans says. “Part of the reason we’re doing these experiments is to predict when events like these happen.”

Scientists are getting ever closer to measuring the corona’s magnetic field. In 2017, solar physicist Jenna Samra of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and her colleagues spotted a particular wavelength of infrared light in the corona for the first time (SN Online: 5/29/18). This wavelength, emitted by iron molecules that have lost several electrons to the corona’s extreme heat, is particularly sensitive to magnetic fields. Future observatories that focus on it could reveal more about coronal magnetism.

This year, Samra’s team will be looking again, in hopes of confirming that 2017 detection. She plans to fly an aircraft in the shadow of the sun with a special spectrometer aimed out the window. Over the last two years, she and her colleagues have improved the instrument’s sensitivity by a factor of 20, meaning the corona will look 20 times as bright as it did in 2017.

“We want to understand which of our emission lines are useful for future measurements of the magnetic field,” she says.

2. Less of the total eclipse will cross land.

Most of 2017’s total eclipse was visible from land, covering about 4,600 kilometers from near Salem, Ore., to Charleston, S.C. That gave scientists a comparatively long time in the dark — about an hour and a half from coast to coast. Comparing the corona’s appearance from west to east let researchers measure how the corona changed over that period.

This year, the path of totality covers a chunk of the southern Pacific Ocean and a narrower swath of land, roughly 2,000 kilometers from western Chile to eastern Argentina. A partial eclipse will visible across other parts of the two countries as well as Paraguay, Uruguay, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador and parts of Brazil, Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica and Nicaragua.

The moon is also closer to Earth this time. So the spot with the longest duration of totality will see four minutes and 32 seconds of darkness, but unfortunately, that spot is in the middle of the southern Pacific Ocean. (In 2017, the same period was about two and a half minutes.)

Back in Chile, scientists can expect about two and a half minutes of totality. Because totality will happen a few hours before sunset, around 4:39 p.m. local time, many researchers are heading as far west in the country as possible to catch the maximum amount of obscured daylight.

Some groups still hope to get a longer stretch of corona watching time. Solar physicist Shadia Habbal of the University of Hawaii in Honolulu is leading a team that will spread out over three sites, one at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in northern Chile and two in Argentina, giving the team a total of about seven minutes in totality.

Other scientists are turning to the air. Astronomer Glenn Schneider of Steward Observatory at the University of Arizona in Tucson will chase the moon’s shadow in an airplane for nearly eight minutes of totality near Easter Island. And an hour later, totality will reach Pasachoff on the ground in Chile, giving the pair roughly the same total amount of time in totality as Pasachoff’s team got in 2017.

With all those sets of observations, “we’ll be able to see what might be changing and measure velocities of things in the solar corona,” Pasachoff says.

3. The sun will be low in the sky.

That sunset eclipse might be beautiful to view. But it makes the science more difficult. By the time totality begins, the sun will be just 13 degrees above the horizon. Scientists will have to look through more of the Earth’s atmosphere to see the corona, leading to blurrier images.

Pasachoff expects the blur to be bad enough that he’s not bothering with one measurement he did in 2017. Then, his team looked for rapid oscillations in a particular wavelength of light to measure the corona’s temperature, and test why it’s so much hotter than the solar surface (SN Online: 8/20/17).

“We’re not working on that question this time,” he says. “We’ll do it next time.”

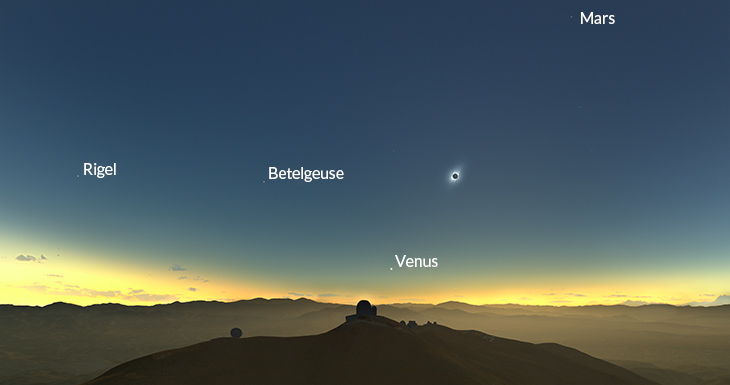

4. Observatories offer good viewing spots, but the telescopes themselves are largely useless.

The path of the eclipse’s totality crossing over South America has another big advantage: It will pass right over several of the world’s most powerful observatories, built on sites chosen partly for the clear, dry mountain weather. Those conditions improve chances of seeing totality and not getting clouded out.

But none of the telescopes at Cerro Tololo or the European Southern Observatory’s La Silla site will actually be able to aim at the eclipse. Designed to collect as much light as possible from the night sky, they could catch fire if they observed the sun directly.

“You think, the eclipse is passing over these big observatories, they already have big telescopes in place, we can just use them!” Bryans says. “Turns out the only real advantage from the observatories is the nice location.”

Editor’s note: This story was updated July 1, 2019, to correct astronomer Jay Pasachoff’s location. While some of his team members will be at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in northern Chile, he will be near La Higuera, Chile.