American whiskeys leave unique ‘webs’ when evaporated

Different types of bourbon leave behind signature weblike designs

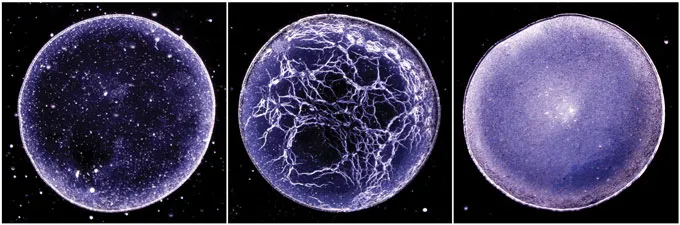

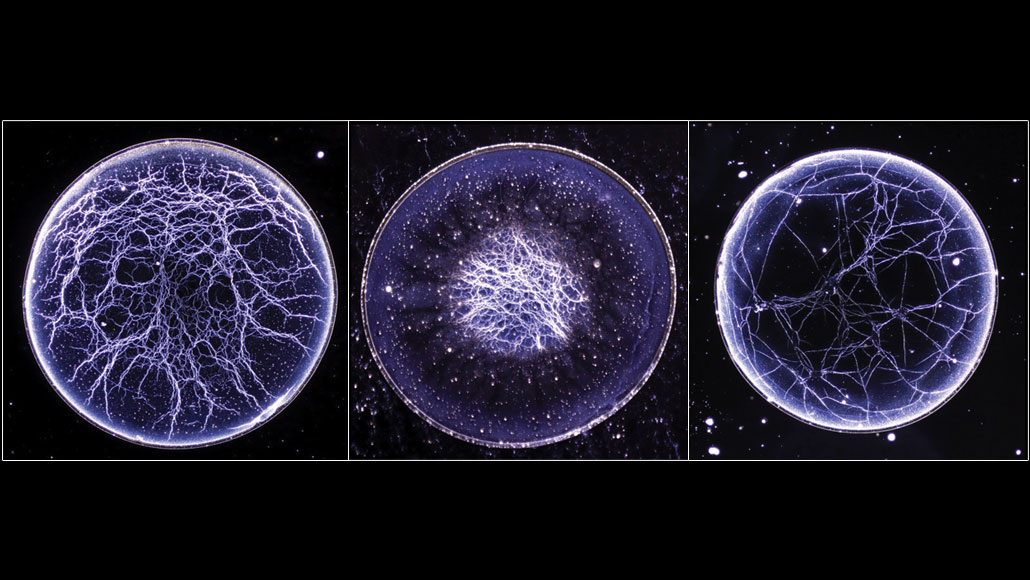

When evaporated, droplets of different American whiskeys (left to right: Maker's Mark, Pappy Van Winkle’s and Jack Daniel’s) leave behind unique, weblike residues not seen in Scotch whiskies or other liquors.

S.J. Williams, M.J. Brown, VI and A.D. Carrithers/Physical Review Fluids 2019