The appendix is implicated in Parkinson’s disease

Having an appendectomy lowered the risk of developing the neurodegenerative disease

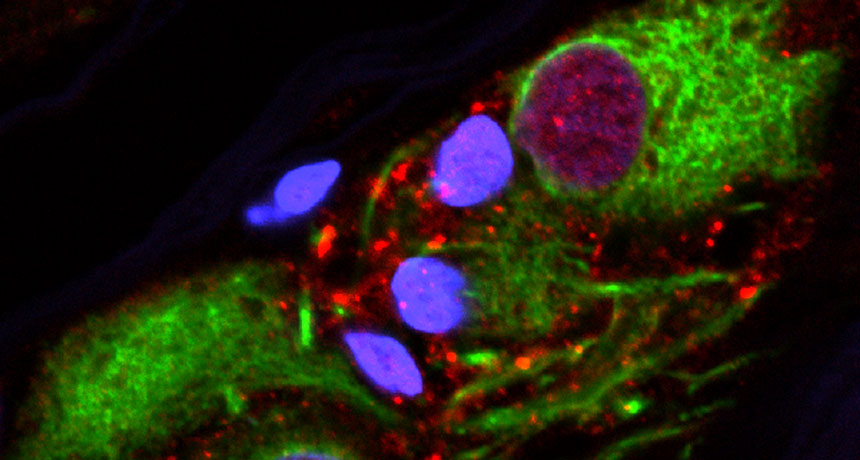

CLUMPS FOUND HERE Globs of alpha-synuclein protein (red) found in appendix tissue from healthy individuals add to evidence that the gut plays a role in the development of Parkinson’s disease.

V. Labrie/Van Andel Research Institute

The appendix, a once-dismissed organ now known to play a role in the immune system, may contribute to a person’s chances of developing Parkinson’s disease.

An analysis of data from nearly 1.7 million Swedes found that those who’d had their appendix removed had a lower overall risk of Parkinson’s disease. Also, samples of appendix tissue from healthy individuals revealed protein clumps similar to those found in the brains of Parkinson’s patients, researchers report online October 31 in Science Translational Medicine.

Together, the findings suggest that the appendix may play a role in the early events of Parkinson’s disease, Viviane Labrie, a neuroscientist at the Van Andel Research Institute in Grand Rapids, Mich., said at a news conference on October 30.

Parkinson’s, which affects more than 10 million people worldwide, is a neurodegenerative disease that leads to difficulty with movement, coordination and balance. It’s unknown what causes Parkinson’s, but one hallmark of the disease is the death of nerve cells, or neurons, in a brain region called the substantia nigra that helps control movement. Lewy bodies, which are mostly made of clumped bits of the protein alpha-synuclein (SN: 1/12/13, p. 13), also build up in those neurons but the connection between the cells’ death and the Lewy bodies isn’t clear yet.

Symptoms related to Parkinson’s can show up in the gut earlier than they do in the brain (SN: 12/10/16, p. 12). So Labrie and her colleagues turned their attention to the appendix, a thin tube around 10 centimeters long that protrudes from the large intestine on the lower right side of the abdomen. Often considered a “useless organ,” Labrie said, “the appendix is actually an immune tissue that’s responsible for sampling and monitoring pathogens.”

In the new study, Labrie’s team analyzed health records from a national registry of Swedish people, some of whom were followed for as many as 52 years. That long observation time was key: People have their appendix removed most often in their teens or 20s but, on average, don’t develop Parkinson’s disease until their 60s. More than half a million people in the registry had had an appendectomy, while a total of 2,252 people out of the 1.7 million developed Parkinson’s.

For people without an appendix, the incidence of Parkinson’s disease was 1.6 per 100,000 people per year compared with about 2 per 100,000 per year for those with the organ. Removing the appendix was associated with a 19 percent drop in the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease, the team reports.

Labrie and her colleagues also compared people in the registry from rural and urban areas. Past research has found that rural living comes with a higher chance of developing Parkinson’s, perhaps due to pesticide exposure (SN: 12/2/00, p. 360). Indeed, rural residents who’d had their appendix removed had a 25 percent lower risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. There wasn’t a benefit for city dwellers.

Surgical samples from a tissue bank of appendixes from 48 people without Parkinson’s provided another link to the disease. The team discovered alpha-synuclein clumps in 46 of the samples — from both old and young patients — similar to those seen in the brains of Parkinson’s patients. The clumped protein has been found in other areas of the gut, and past research suggests that it’s possible for the protein to travel along the main nerve that connects the gut to the brain (SN: 12/10/16, p. 12).

If the clumped protein in the appendix turns out to jump-start the disease, Labrie said, “preventing excessive alpha-synuclein clump formation in the appendix, and its departure from the gastrointestinal tract, could be a useful new form of therapy.”

Ongoing clinical trials are investigating different strategies to remove alpha-synuclein from the brain. If a new therapy could clear the protein from the brain, says John Trojanowski, a neuropathologist at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine who was not involved in the new study, perhaps it would do the same for the appendix. “Every facet of what contributes to Parkinson’s disease is important,” he says.