“The very thing!” exclaimed Professor Wogglebug, bounding into the air and upsetting his gold inkwell. “The very next idea!”

Devotees of L. Frank Baum’s classic children’s books would quickly recognize the above excerpt as the opening of the 15th book in the Oz series, The Royal Book of Oz. They might be harder pressed to say whether these lines were actually written by Baum. The book appeared with Baum’s name on the cover in 1921, which was 2 years after Baum’s death, and it was billed as the final work of the Royal Historian of Oz. For decades, however, fans and scholars have speculated that Ruth Plumly Thompson, who took over the series after Baum died, was the true author.

A few decades ago, literary detectives might have pinned their hopes of solving this mystery on finding the proverbial dusty manuscript in the attic trunk. Today, some scholars are tackling such problems with untraditional but more widely available tools: math formulas and computer programs.

Earlier this year, statistician José Binongo of the Collegiate School and Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond published the results of statistical tests making a compelling case that Thompson wrote The Royal Book of Oz. Binongo’s paper appeared in the spring Chance, in a special issue on stylometry–the science of measuring literary style.

Stylometry is now entering a golden era. In the past 15 years, researchers have developed an arsenal of mathematical tools, from statistical tests to artificial intelligence techniques, for use in determining authorship. They have started applying these tools to texts from a wide range of literary genres and time periods, including the Federalist Papers, Civil War letters, and Shakespeare’s plays.

“We can now pretty accurately identify authorship–under the right conditions,” says John Burrows, an emeritus English professor of the University of Newcastle in Australia.

What’s more, the tremendous growth of computer power and electronic archives of literary texts is allowing stylometrists to carry out mathematical analyses on a scale previously unimaginable.

“Stylometry has a tremendous untapped potential,” says Bernard Frischer, a classicist at the University of California, Los Angeles. He has used mathematical methods to study ancient Greek and Latin texts. “There are hundreds of insights waiting to be discovered by scholars who will take the time to learn statistics and computer programming,” he says.

Literary fingerprints

At first glance, it might appear that the way to pinpoint a writer’s style is to study the rarest, most striking features of his or her writing. After all, it’s the unexpected words and the unusual rhetorical flourishes that seem to mark a work as uniquely Shakespearean or Dickensian.

Yet the most venerable, commonly used approach of stylometrists does the opposite: It examines how writers use bread-and-butter words such as “to” and “with.” Although this approach seems counterintuitive, it’s based on sound logic.

“People’s unconscious use of everyday words comes out with a certain stamp,” says David Holmes, a stylometrist at the College of New Jersey in Ewing. Precisely because writers use these function words without thinking about them, they may offer more-reliable fingerprints of a writer’s style than unusual words do.

“Rare words are noticeable words, which someone else might pick up or echo unconsciously,” Burrows says. “It’s much harder for someone to imitate my frequency pattern of ‘but’ and ‘in’.”

In the early 1960s, statisticians Frederick Mosteller and David Wallace launched the use of function words to determine authorship. They analyzed the Federalist Papers, 85 essays published anonymously in 1787 and 1788 to persuade New Yorkers to adopt the new Constitution of the United States. Scholars have long known that Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay wrote the essays, but both Hamilton and Madison claimed authorship of 12 of the papers.

To determine who wrote the disputed papers, Mosteller and Wallace compared word usage in other writings by Hamilton and by Madison. They found, for instance, that Hamilton used the word “upon” about 10 times as often as Madison did. Armed with 30 such distinguishing words, Mosteller and Wallace considered each disputed paper.

Mosteller and Wallace started out by assuming that for each paper, the probability was equal that Madison or Hamilton was the author. They then used the frequencies of the 30 words, one word at a time, to improve this probability estimate. They ultimately assigned all 12 disputed papers to Madison, a conclusion that dovetails with the historians’ prevailing view.

Mosteller and Wallace’s landmark study was the first convincing demonstration that stylometry can ferret out the authorship of a text, Holmes says. Since that time, the Federalist Papers has been a favorite testing ground for researchers trying out new stylometric methods.

Many dimensions

Although Mosteller and Wallace’s study made a big splash, their techniques were not widely picked up, largely because of the shortage of computing power and machine-readable text at the time. By the late 1980s, that was changing. About this time, Burrows found a way to apply a statistical technique that has become, Holmes says, the “first port of call” for stylometrists.

Like Mosteller and Wallace, Burrows examined the frequency of function words. However, whereas Mosteller and Wallace incorporated information one word at a time, Burrows’ analyzed the information from all the words in one fell swoop. Researchers have now widely adopted Burrows’ technique, making various modifications along the way.

Binongo’s work on The Royal Book of Oz is a good example. He started by collecting other samples of Baum’s and Thompson’s writings and breaking the samples into 5,000-word chunks. He then found the 50 most frequently used words in the body of texts and counted how often each word appeared in each chunk. This process distilled each chunk to 50 numbers.

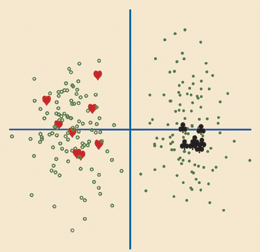

Just as two numbers specify a point in two-dimensional space, and three numbers a point in three-dimensional space, the 50 numbers associated with each chunk of text specify a point in 50-dimensional space. Any differences in the scatter of Baum’s and Thompson’s points could be potential clues to the writers’ different styles.

The problem is, people aren’t good at visualizing spaces with more than three dimensions. So, Binongo employed a tool called principal-components analysis (PCA) to squash all the different dimensions onto a flat plane. PCA finds the plane that captures as much as possible of the original variation in the scattered points.

There’s no guarantee that a pattern will show up in this plane. In the case of the Oz books, however, a pattern leaps out. The Baum texts cluster in one half of the plane, while the Thompson texts sit in the other half, showing what Binongo calls a clear “stylistic gulf.”

When chunks of The Royal Book of Oz are plotted in the same plane, they all land squarely in Thompson’s half.

“With this unerring consistency, we have confidence in our identification of Thompson as the author of the 15th book,” Binongo said in the spring issue of Chance.

In the same issue, Holmes reported using PCA and other function-word techniques to resolve another historical mystery, the authorship of the “Pickett letters.” This collection was supposedly written during the Civil War by Confederate General George Pickett to his fiancée, but she actually wrote the letters herself, Holmes concludes.

Artificial smarts

For decades, computers have supported the work of experts in stylometry. Now, computers are becoming experts in their own right, as some researchers apply artificial intelligence techniques to the question of authorship.

In 1993, Robert Matthews of Aston University in England and Thomas Merriam, an independent Shakespearean scholar in England, created a neural network that could distinguish between the plays of Shakespeare and of his contemporary Christopher Marlowe. A neural network is a computer architecture modeled on the human brain, consisting of nodes connected to each other by links of differing strengths.

Matthews and Merriam built such a network in which the links initially had random strengths. They then trained the network by presenting it with examples of undisputed texts by Shakespeare or Marlowe. Any time the network guessed the wrong author for one of the training texts, it adjusted the strength of its links. By the end of the training period, the network could accurately distinguish between the known Shakespeare and Marlowe texts.

When the technique was applied to the entire canon of Shakespeare plays, Henry VI, Part 3 was the only text that the network classified as written by Marlowe. This result lent support to the controversial view of some scholars that Shakespeare adapted the play from an earlier work of Marlowe. Several other early Shakespeare plays also showed strong Marlowe traits, although the network ultimately attributed them to Shakespeare.

The results support the idea that “in the early 1590s, Shakespeare made the transition from actor to the most accomplished playwright of his or anyone else’s era–by amending preexisting scripts by Marlowe,” Matthews says.

A couple of years later, Holmes and Richard Forsyth of the University of Luton in England used the Federalist Papers to test another artificial intelligence technique. They applied genetic algorithms, which use Darwinian principles of natural selection. The idea is to create a set of rules for determining authorship and then let the most useful, or fit, rules survive.

Holmes and Forsyth began by creating 100 rules. An example of a rule might be, “If but appears more than 1.7 times in every thousand words, then the text is by Madison.” Of course, that particular rule might do a terrible job.

Holmes and Forsyth tested each rule against known texts of Madison and Hamilton and gave it a fitness score on the basis of how many texts it assigned correctly. They then killed the 50 least-fit rules, introduced small mutations into the surviving rules to mimic evolution, and added 50 new rules.

They repeated this process again and again until, after 256 generations, the evolved rules attributed the texts correctly. When tested on the disputed papers, the rules attributed them all to Madison, in keeping with Mosteller and Wallace’s findings.

In contrast to Mosteller and Wallace’s work, the genetic algorithm’s final rules used only eight words. “It worked extremely well, and very efficiently,” Holmes says.

Yet another analysis of the Federalist Papers was presented at a computer science conference in October. Glenn Fung of Siemens Medical Solutions in Malvern, Pa., used one of artificial intelligence’s newest tools, a pattern-recognition technique called support-vector machines.

As does PCA, the new technique plots each chunk of text as a point in a high-dimensional space. It then searches for the best-fitting surface that divides the points belonging to one author from those of the other author. Fung’s analysis used only three characteristic words–to, upon, and would–to successfully attribute the disputed papers to Madison.

Habitual phrases

Although it’s risky to determine authorship using rare words, they can strengthen evidence of a match. “We shouldn’t dismiss the rare words, since they have as interesting a story to tell as the high-frequency words do,” Holmes says. “Ideally, these two things should work in harmony.”

For instance, in Shakespeare, Co-Author (Oxford University Press, 2003), Brian Vickers of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich uses common-word results, rare-word results, and historical information to argue that five of the plays usually included in the Shakespeare canon are in fact collaborations between Shakespeare and other dramatists.

Hugh Craig, a stylometrist at the University of Newcastle, has been pursuing an idea, which he calls “rare pairs.” He attributes it to MacDonald Jackson of the University of Auckland in New Zealand. Rare pairs are two words that, taken separately, are nothing special but which are seldom seen in close proximity.

Craig hopes that these pairs, by capturing something of an author’s favorite phrases, might provide a stronger clue to authorship than individual words do. “The idea is that authors have certain habits, maybe even laid down as neural pathways, that predispose them to pair one word with another,” he says. “Once one word comes into their mind, they’re primed to use a second word.”

As a test case, Craig has been studying a collection of scenes that were added by an anonymous author in 1602 to a play called The Spanish Tragedy, after its author, Thomas Kyd, was already dead. The added scenes are of high quality, Craig says, and some critics have speculated that Shakespeare wrote them.

Craig culled from an online database all the works by dramatists of the period–a collection containing nearly 17 million words. He defined a pair to be rare if it turns up at most 10 times in the database.

One example in The Spanish Tragedy additions is paint and wound, which appear in the line “Canst paint me a tear or a wound,/ A groan or a sigh?” In the entire database, Craig found only two other uses of this pair, one by an obscure author named Sir David Murray, and the other in Shakespeare’s 1594 poem “The Rape of Lucrece”: “And drop sweet balm in Priam’s painted wound.”

Of course, a single such congruence is evidence of nothing. The idea, Craig says, is to look at many examples and see whether they point towards a particular author. Craig is currently working out how large a database is necessary and how many rare-pair matches are needed to assert the authorship of a text with confidence.

For The Spanish Tragedy, Craig says, the 78 rare pairs he has tested so far put Shakespeare ahead of the other favored candidates. “More work needs to be done before [the scenes] are accepted as part of future editions of Shakespeare, but I think it’s quite possible they will appear there eventually,” he said in a September lecture at the Massachusetts Center for Renaissance Studies in Amherst.

Style limits

There will always be some authorship questions that stylometry can’t touch. For instance, most of the methods require the unknown text to contain at least 1,000 words. “You can’t do authorship attribution on one paragraph,” says Joseph Rudman, a stylometrist at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

It’s also essential to work with clean text that hasn’t been changed much over the years. Rudman notes, so stylometry can’t be applied to poems from the oral tradition. “They’re such a mishmash,” he says.

Stylometrists dream of a technique they could use to settle any attribution problem, regardless of genre, language, or time period. In the meantime, though, the methods at hand can provide fresh insight into many literary mysteries. “Stylometrics offers vast potential for new discoveries,” Frischer says. “It has a very bright future.”

****************

If you have a comment on this article that you would like considered for publication in Science News, send it to editors@sciencenews.org. Please include your name and location.

To subscribe to Science News (print), go to https://www.kable.com/pub/scnw/

subServices.asp.

To sign up for the free weekly e-LETTER from Science News, go to http://www.sciencenews.org/subscribe_form.asp.