Climate change helped some dinosaurs migrate to Greenland

A drop in CO2 levels helped massive plant eaters trek from South America to Greenland

Sauropodomorphs, such as this Plateosaurus (illustrated), walked about 10,000 kilometers from South America to Greenland when CO2 levels dropped in the atmosphere.

James Kuether/Science Source

A drop in carbon dioxide levels may have helped sauropodomorphs, early relatives of the largest animal to ever walk the earth, migrate thousands of kilometers north past once-forbidding deserts around 214 million years ago.

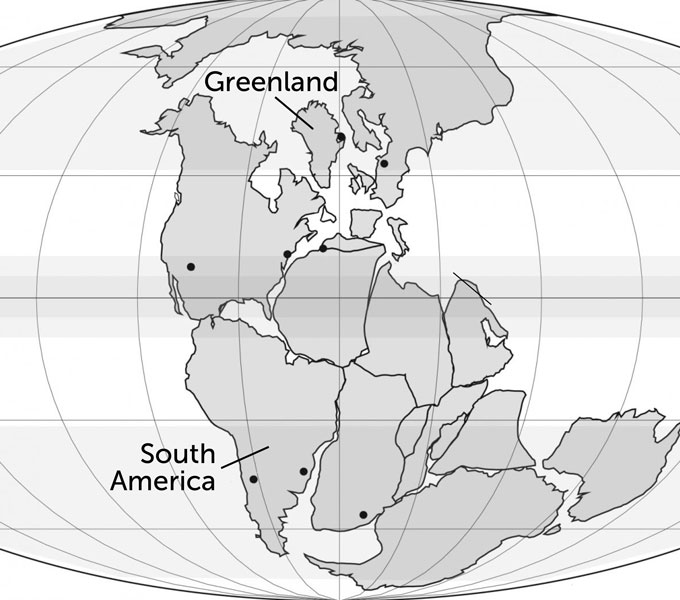

Scientists pinpointed the timing of the dinosaurs’ journey from South America to Greenland by correlating rock layers with sauropodomorph fossils to changes in Earth’s magnetic field. Using that timeline, the team found that the creatures’ northward push coincides with a dramatic decrease in CO2, which may have removed climate-related barriers, the team reports February 15 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The sauropodomorphs were a group of long-necked, plant-eating dinosaurs that included massive sauropods such as Seismosaurus as well as their smaller ancestors (SN: 11/17/20). About 230 million years ago, sauropodomorphs lived mainly in what is now northern Argentina and southern Brazil. But at some point, these early dinosaurs picked up and moved as far north as Greenland.

Exactly when they could have made that journey has been a puzzle, though. “In principle, you could’ve walked from where they were to the other hemisphere, which was something like 10,000 kilometers away,” says Dennis Kent, a geologist at Columbia University. Back then, Greenland and the Americas were smooshed together into the supercontinent Pangea. There were no oceans blocking the way, and mountains were easy to get around, he says. If the dinosaurs had walked at the slow pace of one to two kilometers per day, it would have taken them approximately 20 years to reach Greenland.

But during much of the Late Triassic Epoch, which spans 233 million to 215 million years ago, Earth’s carbon dioxide levels were incredibly high — as much as 4,000 parts per million. (In comparison, CO2 levels currently are about 415 parts per million.) Climate simulations have suggested that level of CO2 would have created hyper-arid deserts and severe climate fluctuations, which could have acted as a barrier to the giant beasts. With vast deserts stretching north and south of the equator, Kent says, there would have been few plants available for the herbivores to survive the journey north for much of that time period.

Previous estimates suggested that these dinosaurs migrated to Greenland around 225 million to 205 million years ago. To get a more precise date, Kent and his colleagues measured magnetic patterns in ancient rocks in South America, Arizona, New Jersey, Europe and Greenland — all locales where sauropodomorphs fossils have been discovered. These patterns record the orientation of Earth’s magnetic field at the time of the rock’s formation. By comparing those patterns with previously excavated rocks whose ages are known, the team found that sauropodomorphs showed up in Greenland around 214 million years ago.

That more precise date for the sauropodomorphs’ migration may explain why it took them so long to start the trek north — and how they survived journey: Earth’s climate was changing rapidly at that time.

Around the time that sauropodomorphs appeared in Greenland, carbon dioxide levels plummeted within a few million years to 2,000 parts per million, making the climate more travel-friendly to herbivores, the team reports. The reason for this drop in carbon dioxide — which appears in climate records from South America and Greenland — is unknown, but it allowed for an eventual migration northward.

“We have evidence for all of these events, but the confluence in timing is what is remarkable here,” says Morgan Schaller, a geochemist at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y., who was not involved with this study. These new findings, he says, also help solve the mystery of why plant eaters stayed put during a time that meat eaters roamed freely.

“This study reminds us that we can’t understand evolution without understanding climate and environment,” says Steve Brusatte, a vertebrate paleontologist and evolutionary biologist at the University of Edinburgh, also not involved with the study. “Even the biggest and most awesome creatures that ever lived were still kept in check by the whims of climate change.”