A hunt for fungi might bring this orchid back from the brink

If the work is a success, scientists could possibly regrow the species in the wild

Cooper’s black orchid, a rare, critically endangered species found only in New Zealand, relies on fungi for the nutrients it needs to sprout. Scientists are working to identify the fungi to prevent the flowers from dying out.

Kathy Warburton/inaturalist (CC BY 4.0)

If you ever come across a Cooper’s black orchid in the wild, you probably would mistake it for a stick — or perhaps an odd potato if you dig a little underneath it. Unlike many others of its kind, this delicate flower is devoid of lush green leaves and flashy petals. Its stem lies on the floor of New Zealand’s broadleaf forests for most of the year, only popping up during the summer months to blossom with pendulous brown and white blooms. And rather than growing a tangle of roots, the orchid sprouts a pale brown tuber.

But the chances of encountering a Cooper’s black orchid (Gastrodia cooperae) are getting slimmer. Fewer than 250 adult plants have been found since botanist Carlos Lehnebach identified the species in 2016, and they live in only three sites across New Zealand. To make matters worse, feral pigs, rabbits and other animals like to nosh on the tubers. And the forests where the orchid grows are being cleared for farmland (SN: 12/21/20). In 2018, New Zealand’s Department of Conservation classified the orchid as nationally critical, emphasizing its high risk of extinction.

At the Lions Ōtari Plant Conservation Laboratory in Wellington — part of the country’s only botanical garden focused on native plants — Lehnebach and colleagues are working to bring Cooper’s black orchid back from the brink (SN: 9/6/18).

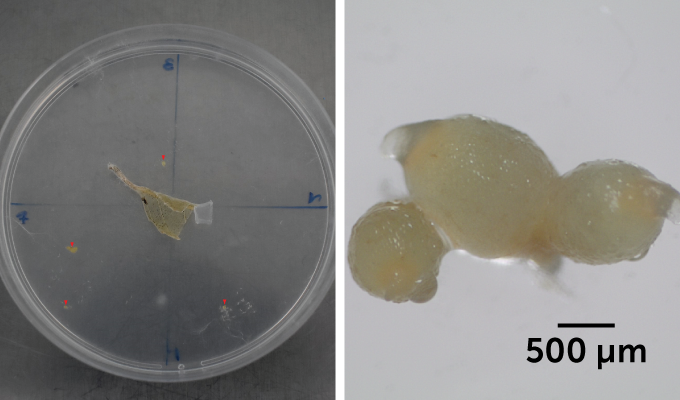

From one of the lab’s three fridge-sized incubators, conservationist Jennifer Alderton-Moss pulls out dozens of petri dishes containing the orchids’ speck-sized seeds and root-emanating tubers.

The researchers dissect the roots under a microscope to look for fungi that could help the seeds germinate. Early in life, most orchids rely on fungi for essential nutrients and minerals. To conserve Cooper’s black orchids, the team needs to identify exactly which fungal species supplies the plant with nutrients. DNA testing helps the team rule out known orchid pathogens. Potential candidates are then extracted from roots and grown on petri dishes. Once they’re mature enough, fungi get paired up with seeds on another dish.

“We’re working with a rare species, so we can’t just [take] hundreds of seeds,” says conservationist Karin van der Walt. The team first tested its methods on Gastrodia sesamoides, a common orchid that also grows tubers. “If we get it wrong, at least we’re not causing extinction,” she says.

It took the researchers about a year of trial-and-error to find the right germination method for Cooper’s black orchid. Once they did, they had to wait another two to four months for the seeds to sprout.

Alderton-Moss removes a dish from a resealable bag and points out a fungus, an orchid leaf for the fungus to feed on and a few seeds that have now developed into light brown tuberlike grains. Cooper’s black orchid may have finally found its perfect match in Resinicium bicolor.

Commonly known as white-rot fungus, R. bicolor is a scourge on Douglas fir trees — a farmed nonnative tree in New Zealand — but seems to provide Cooper’s black orchid seeds with the nutrients and minerals they need to germinate. The next step is to grow Cooper’s black orchid plants from seedlings. That will reveal whether the fungus that helps seeds germinate is the same one that sustains the adult plant.

In the meantime, seeds and fungi are kept in a chilly slumber in one of the lab’s sterile rooms. Seeds are stored inside an incubator at –18° Celsius, while fungi are stored inside a cryogenic container with liquid nitrogen at –200° C. “If we lose [the orchid entirely], we have seeds banked in the lab,” van der Walt says. “We can at least grow them back — we know we can get that far.”

To test the viability of banked seeds and fungi, the team plans to thaw them at quarterly intervals to see how much they’ll grow.

Ultimately, researchers want to seed wild areas with this plant-fungi pair to boost the population — without all the lab steps. Though there are still other factors to work out to make wild growth a reality, the lab technique is “a powerful way to prevent extinction,” van der Walt says, not only for the Cooper’s black orchid but other endangered species, too.