How making a COVID-19 vaccine confronts thorny ethical issues

A shot at COVID-19 vaccine development shows the ethical issues behind commonly used cell lines

A COVID-19 vaccine comes with many ethical questions. Even before we ask who should get it, some are questioning how they should be developed.

Manjurul/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Ethical concerns abound in the race to develop a COVID-19 vaccine. How do we ethically test it in people? Can people be forced to get the vaccine if they don’t want it? Who should get it first?

Tackling those questions demands that a vaccine exist. But a slew of other ethical questions arise long before anything is loaded into a syringe. In particular, some Catholic leaders in the United States and Canada are concerned about COVID-19 vaccine candidates made using cells derived from human fetuses aborted electively in the 1970s and 1980s. The group wrote a letter to the commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in April, expressing concern that several vaccines involving these cell lines were selected for Operation Warp Speed — a multibillion-dollar U.S. government partnership aimed at delivering a COVID-19 vaccine by January 2021.

The group urged the FDA to instead provide incentives for COVID-19 vaccines that do not use fetal cell lines. But, as virologist Angela Rasmussen of Columbia University pointed out on Twitter, those other vaccines are being developed with scientific input from research using HeLA cells — which come with their own thorny ethical issues of consent.

Here’s how scientists and bioethicists are thinking about the cell lines they use as they develop COVID-19 vaccines.

What are cell lines, and what is their connection to vaccine research and development?

Cell lines are cultures of human or other animal cells that can be grown for long periods of time in the lab. Some of these cultures are known as immortalized cell lines because the cells never stop dividing. Most cells can’t perform this trick — they eventually stop splitting and die. Immortal cell lines have cheated death. Some are more than 50 years old.

Cell lines can be manipulated to become immortal. Or sometimes, immortality arises by chance. “Whenever people make primary cell cultures from different organs of different animals, every so often you just get … lucky, and some cultures just won’t die,” explains Matthew Koci, a viral immunologist at North Carolina State University in Raleigh. Such long-lasting cell lines go on to get studied, and studied some more. Some end up being used in labs around the world.

Immortalized cell lines are crucial for many different types of biomedical research, not just vaccines. They’ve been used to study diabetes, hypertension, Alzheimer’s and much more. Some are human cells, but many also come from animal models. For example, many COVID-19 studies — beyond just those related to vaccines — are using Vero cells, a cell line derived from the kidney of an African green monkey, Rasmussen says.

Two common immortalized cell lines go by the monikers HEK-293 and HeLa. HEK-293 is a cell line isolated from a human embryo that was electively aborted in the Netherlands in 1973. Catholic leaders and other antiabortion groups have objected to the use of HEK-293 in the development of some COVID-19 vaccine candidates. Cells derived from elective abortions, including HEK-293, have been used to develop vaccines, including rubella, hepatitis A, chickenpox and more. Other fetal cell lines, such as the proprietary cell line PER.C6, are also used in vaccine development, including for COVID-19.

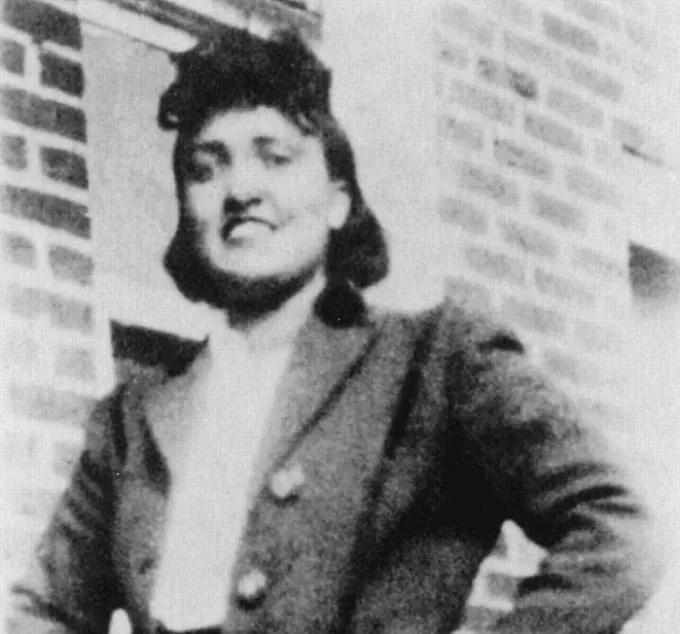

HeLa cells are named after Henrietta Lacks, a Black tobacco farmer and mother of five from Virginia who was diagnosed with cervical cancer in 1951. That cell line comes from a sample taken from her cervix by researchers at Johns Hopkins University when she was undergoing treatment there. These cells have been used in development of vaccines including the polio and human papilloma virus, or HPV, vaccines. They’ve even contributed to our understanding of the human genome.

Are human immortalized cell lines necessary to make COVID-19 vaccines?

More than 125 candidate vaccines against COVID-19 are under development around the world. As of July 2, 14 were in human trials.

Those vaccines can be divided into a few different types. Some, such as RNA vaccines made by companies like Moderna (SN: 5/18/20), do not require a live cell, and thus, no cell line. But other types do require live cells during their production. That includes candidates that use the old-school method for developing vaccines: attenuation. This is “what Pasteur did” when he made the first vaccines against anthrax and rabies, explains Mark Davis, a virologist at Stanford University. “You grow a virus,” and over time the virus loses potency. “It’s still alive, but for some reason, it typically loses its more dramatic clinical effects.”

In another type of vaccine under development called viral-vector, the viral genes to produce immunity to the coronavirus are placed in another, harmless virus. That new combined virus is then grown in cells.

In vaccine development in general, “if we’ve got a virus that has to go through its life cycle, that happens in cell lines,” Koci says.

Many current vaccines, such as those for influenza, hepatitis B and HPV, are grown in nonhuman cell lines and even chicken eggs, bacteria or yeast. But human cell lines are especially useful when working with a new virus, Koci explains. “We don’t know what’s really important” yet in how the coronavirus replicates, he says. There’s no guarantee that a nonhuman cell line will work immediately. Over a few years of work, Koci says, a COVID-19 vaccine might be developed that could be grown in yeast or chicken eggs. But we don’t have years. “We want to make [the system] look as [much like] a human cell as we can.”

This is where immortal cell lines come in.

HEK-293 cells, for example, are especially useful for vaccine work, Rasmussen explains. It’s easy to put new viral genes in them, she says, and once they have the genes inside, HEK-293 cells can pump out large amounts of viral protein — exactly what’s needed to help people develop an immune response.

HeLa are also relatively easy to work with. They can be used to analyze how the coronavirus enters cells to hijack their machinery, for example. “It’s great to have them in the arsenal,” Rasmussen says. But, she says, it’s important to “think about their origins.”

What are some of the moral or ethical issues associated with cell lines such as HEK-293 and HeLa?

No matter what cell line is used, ethical questions will need to be answered. Cell lines derived from animals have all the ethical complications associated with animal research. But in the case of fetal cells, some anti-abortion groups are opposed to using anything that involves fetal cell lines anywhere in its development. The basis for the objection comes down to the idea that if you use anything derived from an abortion, you are in some small way complicit in the abortion itself.

Fetal cell lines have been widely used in basic science and clinical medicine for decades, says Nicholas Evans, a bioethicist at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. “Chances are if you have had a medical intervention in this country or pretty much any other country, you have benefited from the use of these cell lines in some way.”

Catholics got permission in 2005 and 2017 from the Vatican’s Pontifical Academy for Life to get vaccines that use historical fetal cell lines, if no alternatives are available. “The reason is that the risk to public health, if one chooses not to vaccinate, outweighs the legitimate concerns about the origins of the vaccine,” Evans explains. Of course, many people who are anti-abortion are not Catholic, and not all Catholics agree.

In the case of HeLa cells, the ethical problems began the day the cells were taken from Lacks, who was never told that her cells might be used for experimentation. “There was no informed consent. She wasn’t aware, and her family wasn’t aware,” says Yolonda Wilson, a bioethicist at Howard University in Washington, D.C. “The use of this Black woman’s body has I think contributed to a kind of cultural memory of mistrusting health institutions among Black folks,” she says. “It’s not this one-off … it’s a larger narrative of disrespecting Black patients, using Black people and Black bodies in experiments.”

In 2010, science writer Rebecca Skloot wrote a book about Lacks’ story. Since then, Wilson says, “Johns Hopkins University, at least, seems to recognize the ethical issues involved and [is] taking steps to repair some of the damage that has been done.” The university has worked closely with members of Lacks’ family to create scholarships, awards and symposiums about medical ethics. The university will also be constructing a building to be named in Lacks’ honor. But Wilson notes that damage still remains in the broader Black community.

How should those ethical issues be taken into account in COVID-19 vaccine development?

There’s no avoiding immortal cell lines. “Certainly I would expect they would be involved in some of the work, directly or not” in any vaccine that comes out, Rasmussen says. Even though HeLa cells or HEK-293 cells might not be used in the production of a particular COVID-19 vaccine, they are being used as scientists work to understand the virus. Some knowledge gained from those cell lines will go into a vaccine, at the very least.

But for HeLa cells in particular, Wilson says, there’s an opportunity for restorative justice. Given the disproportionate effects of the virus among Black people in the United States due to underlying health conditions and jobs that may expose them more to the virus (SN: 4/10/20), “special effort should be made to ensure that Black people are vaccinated once we know that this is safe,” she says. Latino people have been similarly hard-hit by COVID-19.

Wilson also notes that it’s an opportunity to help researchers think more about the history and context of their work. “It’s important not to act as though the science that happens is divorced from the communities in which it happens.”

The world is waiting anxiously for a COVID-19 vaccine. But as work to make a vaccine goes on, scientists need to think about the materials they use and why, Rasmussen says. “I think probably more [scientists] think about HeLa cells in this way,” she explains. “Many of us have read Skloot’s excellent book.” But that doesn’t mean that scientists could, or should, stop using HeLa cells entirely. In the end, she says, “you’re going to use the cell type that’s right for the experiment.”

Wilson agrees. Ethical considerations are not about weighing an ethical approach against the need to save lives. “That’s false framing,” she says. “It’s not: Be ethical or save lives. Ethics should guide us in thinking how to save lives.”

Trustworthy journalism comes at a price.

Scientists and journalists share a core belief in questioning, observing and verifying to reach the truth. Science News reports on crucial research and discovery across science disciplines. We need your financial support to make it happen – every contribution makes a difference.