How four summer camps in Maine prevented COVID-19 outbreaks

Testing and “bubbles” were behind the successful efforts

Measures to limit the spread of the coronavirus, like wearing masks, grouping kids together in cohorts and social distancing, helped protect more than 1,000 kids and staff members at summer camps in Maine from getting infected.

Jupiterimages/Creatas/Getty Images Plus

- More than 2 years ago

Read another version of this article at Science News Explores

As the coronavirus hit communities across the United States over the summer, four overnight camps in Maine successfully kept the virus at bay.

Of 1,022 people who attended the summer camps, which included campers and staff members, only three people tested positive for COVID-19, researchers report August 26 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. That’s because the people who came to Maine from 41 U.S. states, Puerto Rico, Bermuda and five other countries diligently followed public health measures put in place to stop transmission, the team says.

The camps’ success, as well as others including child care programs in Rhode Island that limited coronavirus transmission, could point to a path forward for places like schools that are reopening with in-person classes in the face of the ongoing pandemic, though challenges remain.

At the camps, a combination of testing, social bubbles, social distancing, masks, quarantine and isolation prevented outbreaks.

Before arriving at camp, officials told all 642 children and 380 staff members to quarantine with their households for 10 to 14 days. Attendees were also tested for COVID-19 five to seven days prior to arrival — with the exception of 12 people who had already been previously diagnosed. Four people tested positive for the virus and isolated for 10 days at home before heading off to one of the camps, which were in session at different times from mid-June to mid-August. (Three of the four camps ran for less than 50 days and the other went on for 62 days.)

Once on site, the campers and staff participated in daily symptom checks and activities held largely outdoors. They also hung out in small “bubbles,” or cohorts, that ranged from five to 44 people in size and became like family during the weeks at camp, the researchers say. If people interacted with anyone outside their group, masks and social distancing were required.

“We wanted to give the kids the ability to have a family unit at camp that they didn’t need to be masked or social distanced from,” says Laura Blaisdell, a pediatrician at Maine Medical Center Research Institute in Scarborough who worked on the new report.

Attendees came to Maine via car, bus and plane, and could have been exposed to the virus after their initial test, so officials retested the 1,006 attendees who had never had COVID-19 four to nine days after their arrival.

In that round of testing, two staff members and one camper from three different camps tested positive but never developed symptoms. Their cohorts were quarantined for two weeks, but still “were able to have a camp experience … and continue to have fun and play together,” Blaisdell says. The three positive cases didn’t transmit the virus to anyone else before they were identified. They each remained isolated until they had two negative test results.

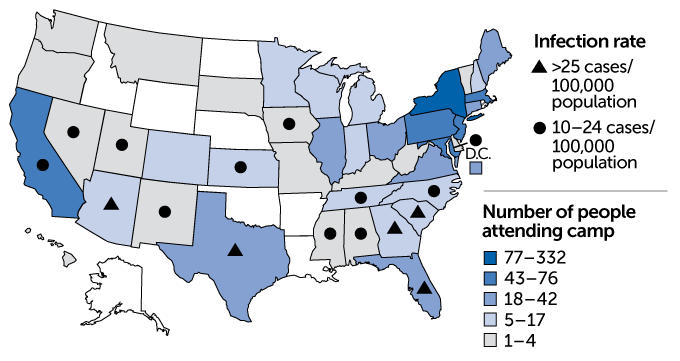

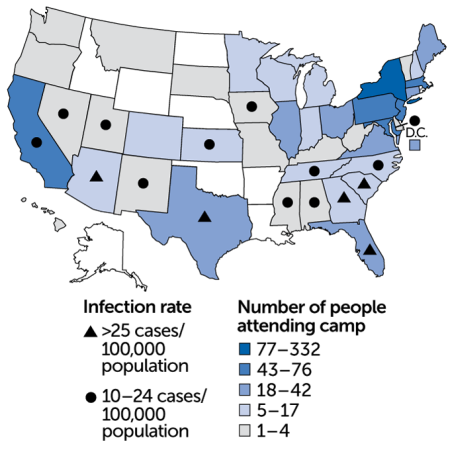

Off to camp

More than 1,000 people from 41 U.S. states, as well as Puerto Rico, Bermuda and several other countries, attended summer camps in Maine from mid-June to mid-August. The map shown here indicates which states campers and staff members came from. (No one attended from states colored white.) A fair number of people traveled from states like Texas and Florida that were hit hard over the summer (seven-day daily average rate of coronavirus infection as calculated on July 1, shown), but the camps’ public health measures prevented outbreaks. States with less than 10 cases per 100,000 population are not designated.

Camp population, by home state, and states’ COVID-19 infection rates

Some people traveled to Maine from areas where COVID-19 cases were surging over the summer, including Texas, Arizona and Florida. But rigorous testing quickly identified potential spreaders, and small cohorts allowed officials to quickly identify those most at risk of catching the virus.

In that way, “cohorting is an unsung hero of public health intervention,” Blaisdell says.

While interventions like cohorts, social distancing and wearing masks can help reduce coronavirus transmission on their own to some extent, each method has limitations. Combining such strategies into a layered approach where people follow multiple guidelines to curb the virus’ spread, like the Maine camps did, can further protect the members of a community.

“Every public health layer is like a layer of Swiss cheese with a hole in it,” Blaisdell says. It’s the stacking of “multiple layers of cheese on top of each other that close those holes and makes for a robust [infectious] disease plan.”

By contrast, a summer camp in Georgia faced an outbreak of the virus even after requiring attendees to provide proof of a negative test before arrival. But there, campers were not required to wear masks, weren’t tested after they arrived at camp and participated in both indoor and outdoor activities (SN: 7/31/20).

Still, the isolated nature of the summer camps in Maine likely made creating a relatively COVID-19–free bubble much easier than it might be at K–12 schools or universities around the country, where people come and go and may not live on site (SN: 8/4/20). There were some staff members at the four camps in Maine who went home every day, but those people were required to wear masks at all times and social distance from other attendees. It also likely helped that the amount of coronavirus circulating in Maine was quite low while the camps were running.

What’s more, the larger the school, the harder it will probably be to make sure that public health interventions are being adhered to. “If you follow the rules, then this can absolutely be successful,” says Brian Nichols, a virologist at Seton Hall University in South Orange, N.J. But, “when you scale it up and start looking at public schools and universities, you just have to plan on the fact that some people aren’t going to follow the rules.”

Nevertheless, the success in Maine hints that containing the virus is possible with a targeted, layered approach, Blaisdell says. “As schools and colleges begin to consider opening, they need to look at their community as a bubble,” she says. “We all need to be making contracts with each other about the behaviors that we’re going to do.”

Trustworthy journalism comes at a price.

Scientists and journalists share a core belief in questioning, observing and verifying to reach the truth. Science News reports on crucial research and discovery across science disciplines. We need your financial support to make it happen – every contribution makes a difference.