COVID-19 can affect the brain. New clues hint at how

Researchers are sifting through symptoms to figure out what the virus does to the brain

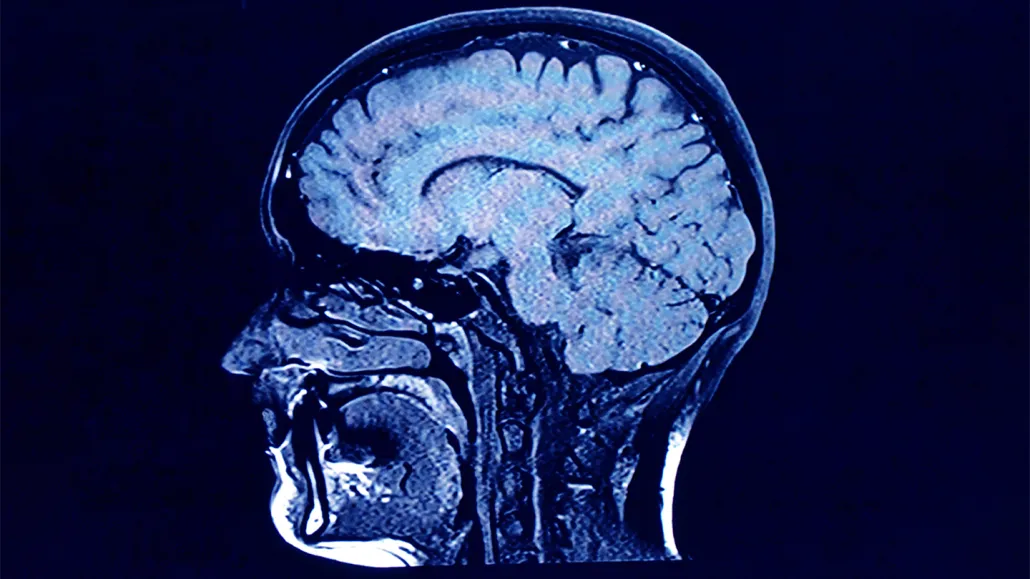

COVID-19 can come with brain-related problems, but just how the virus exerts its effects isn’t clear.

Roxana Wegner/Moment/Getty Images

For more than a year now, scientists have been racing to understand how the mysterious new virus that causes COVID-19 damages not only our bodies, but also our brains.

Early in the pandemic, some infected people noticed a curious symptom: the loss of smell. Reports of other brain-related symptoms followed: headaches, confusion, hallucinations and delirium. Some infections were accompanied by depression, anxiety and sleep problems.

Recent studies suggest that leaky blood vessels and inflammation are somehow involved in these symptoms. But many basic questions remain unanswered about the virus, which has infected more than 145 million people worldwide. Researchers are still trying to figure out how many people experience these psychiatric or neurological problems, who is most at risk, and how long such symptoms might last. And details remain unclear about how the pandemic-causing virus, called SARS-CoV-2, exerts its effects.

“We still haven’t established what this virus does in the brain,” says Elyse Singer, a neurologist at the University of California, Los Angeles. There are probably many answers, she says. “It’s going to take us years to tease this apart.”

Getting the numbers

For now, some scientists are focusing on the basics, including how many people experience these sorts of brain-related problems after COVID-19.

A recent study of electronic health records reported an alarming answer: In the six months after an infection, one in three people had experienced a psychiatric or neurological diagnosis. That result, published April 6 in Lancet Psychiatry, came from the health records of more than 236,000 COVID-19 survivors. Researchers counted diagnoses of 14 disorders, ranging from mental illnesses such as anxiety or depression to neurological events such as strokes or brain bleeds, in the six months after COVID-19 infection.

“We didn’t expect it to be such a high number,” says study coauthor Maxime Taquet of the University of Oxford in England. One in three “might sound scary,” he says. But it’s not clear whether the virus itself causes these disorders directly.

The vast majority of those diagnoses were depression and anxiety, “disorders that are extremely common in the general population already,” points out Jonathan Rogers, a psychiatrist at University College London. What’s more, depression and anxiety are on the rise among everyone during the pandemic, not just people infected with the virus.

Mental health disorders are “extremely important things to address,” says Allison Navis, a neurologist at the post-COVID clinic at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. “But they’re very different than a stroke or dementia,” she says.

About 1 in 50 people with COVID-19 had a stroke, Taquet and colleagues found. Among people with severe infections that came with delirium or other altered mental states, though, the incidence was much higher — 1 in 11 had strokes.

Taquet’s study comes with caveats. It was a look back at diagnosis codes, often entered by hurried clinicians. Those aren’t always reliable. And the study finds a relationship, but can’t conclude that COVID-19 caused any of the diagnoses. Still, the results hint at how COVID-19 affects the brain.

Blood vessels scrutinized

Early on in the pandemic, the loss of smell suggested that the virus might be able to attack nerve cells directly. Perhaps SARS-CoV-2 could breach the skull by climbing along the olfactory nerve, which carries smells from the nose directly to the brain, some researchers thought.

That frightening scenario doesn’t seem to happen much. Most studies so far have failed to turn up much virus in the brain, if any, says Avindra Nath, a neurologist who studies central nervous system infections at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md. Nath and his colleagues expected to see signs of the virus in brains of people with COVID-19 but didn’t find it. “I kept telling our folks, ‘Let’s go look again,’” Nath says.

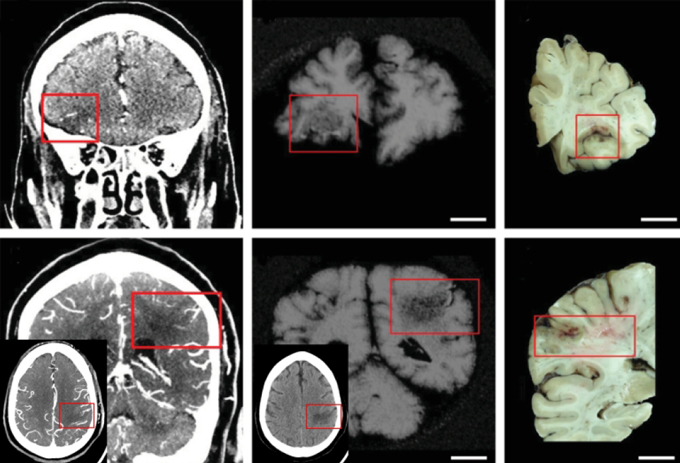

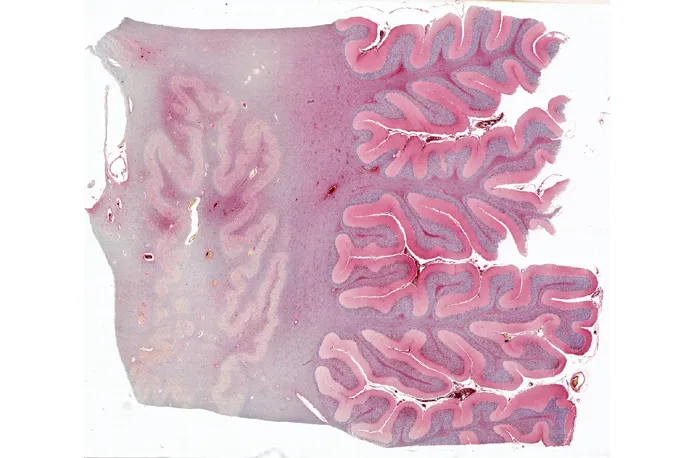

That absence suggests that the virus is affecting the brain in other ways, possibly involving blood vessels. So Nath and his team scanned blood vessels in post-mortem brains of people who had been infected with the virus with an MRI machine so powerful that it’s not approved for clinical use in living people. “We were able to look at the blood vessels in a way that nobody could,” he says.

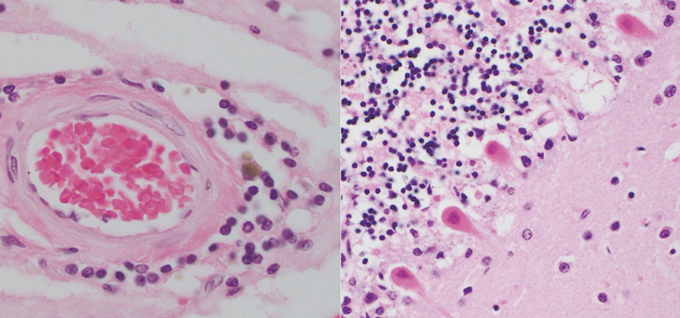

Damage abounded, the team reported February 4 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Small clots sat in blood vessels. The walls of some vessels were unusually thick and inflamed. And blood was leaking out of the vessels into the surrounding brain tissue. “You can see all three things happening at the same time,” Nath says.

Those results suggest that clots, inflamed linings and leaks in the barriers that normally keep blood and other harmful substances out of the brain may all contribute to COVID-related brain damage.

But several unknowns prevent any definite conclusions about how these damaged blood vessels relate to people’s symptoms or outcomes. There’s not much clinical information available about the people in Nath’s study. Some likely died from causes other than COVID-19, and no one knows how the virus would have affected them had they not died.

Inflamed body and brain

Inflammation in the body can cause trouble in the brain, too, says Maura Boldrini, a psychiatrist at Columbia University in New York. Inflammatory signals released after injury can change the way the brain makes and uses chemical signaling molecules, called neurotransmitters, that help nerve cells communicate. Key communication molecules such as serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine can get scrambled when there’s lots of inflammation.

Neural messages can get interrupted in people who suffer traumatic brain injuries, for example; researchers have found a relationship between inflammation and mental illness in football players and others who experienced hits to the head.

Similar evidence comes from people with depression, says Emily Troyer, a psychiatrist at the University of California, San Diego. Some people with depression have high levels of inflammation, studies have found. “We don’t actually know that that’s going on in COVID,” she cautions. “We just know that COVID causes inflammation, and inflammation has the potential to disrupt neurotransmission, particularly in the case of depression.”

Among the cells that release inflammatory proteins in the brain are microglia, the brain’s version of the body’s disease-fighting immune system. Microglia may also be involved in the brain’s response to COVID-19. Microglia primed for action were found in about 43 percent of 184 COVID-19 patients, Singer and others reported in a review published February 4 in Free Neuropathology. Similar results come from a series of autopsies of COVID-19 patients’ brains; 34 of 41 brains contained activated microglia, researchers from Columbia University Irving Medical Center and New York Presbyterian Hospital reported April 15 in Brain.

With these findings, it’s not clear that SARS-CoV-2 affects people’s brains differently from other viruses, says Navis. In her post–COVID-19 clinic at Mount Sinai, she sees patients with fatigue, headaches, numbness and dizziness — symptoms that are known to follow other viral infections, too. “I’m hesitant to say this is unique to COVID,” Navis says. “We’re just not used to seeing so many people getting one specific infection, or knowing what the viral infection is.”

Teasing apart all the ways the brain can suffer amid this pandemic, and how that affects any given person, is impossible. Depression and anxiety are on the rise, surveys suggest. That rise might be especially sharp in people who endured stressful diagnoses, illnesses and isolation.

Just being in an intensive care unit can lead to confusion. Delirium affected 606 of 821 people — 74 percent — while patients were in intensive care units for respiratory failure and other serious emergencies, a 2013 study found. Post-traumatic stress disorder afflicted about a third of people who had been seriously sick with COVID-19 (SN: 3/12/21).

More specific aspects of treatment matter too. COVID-19 patients who spent long periods of time on their stomachs might have lingering nerve pain, not because the virus attacked the nerve, but because the prone position compressed the nerves. And people might feel mentally fuzzy, not because of the virus itself, but because a shortage of the anesthetic drug, propofol, meant they received an alternative sedative that can bring more aftereffects, says Rogers, the psychiatrist at University College London.

Lingering questions — what the virus actually does to the brain, who will suffer the most, and for how long — are still unanswered, and probably won’t be for a long time. The varied and damaging effects of lockdowns, the imprecision doctors and patients use for describing symptoms (such as the nonmedical term “brain fog”) and the indirect effects the virus can have on the brain all merge, creating a devilishly complex puzzle.

For now, doctors are busy focusing on ways in which they can help, even amid these mysteries, and designing larger, longer studies to better understand the effects of the virus on the brain. That information will be key to helping people move forward. “This isn’t going to be over soon, unfortunately,” Troyer says.

Sign up for our newsletter

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.