‘Deaths of despair’ are rising. It’s time to define despair

Scientists investigate whether despair is distinct from mental disorders

Researchers are developing ways to measure despair, distinct from any psychiatric ailment, that has contributed to deaths and mental suffering in the United States for several decades leading up to the current coronavirus pandemic.

Juanmonino/iStock/Getty Images Plus

As 2015 wound down, a foreboding but catchy phrase from a scientific paper blew across the cultural landscape with unexpected force.

The expression “deaths of despair” was born after Princeton University economist Anne Case and Angus Deaton — Case’s colleague, husband and a Nobel laureate in economics — dug into U.S. death statistics and found that, during the 1900s, people’s life spans had generally lengthened from roughly 50 years to nearly 80. But then, near the end of the century, one segment of the population took a U-turn. Since the 1990s, mortality had risen sharply among middle-aged, non-Hispanic white people, especially those without a college degree, Case and Deaton reported in December 2015 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The reason, to a large extent: White, working-class people ages 45 to 54 were drinking themselves to death with alcohol, accidentally overdosing on opioids and other drugs, and killing themselves, often by shooting or hanging. Vanishing jobs, disintegrating families and other social stressors had unleashed a rising tide of fatal despair, Case and Deaton concluded. This disturbing trend mirrored what had previously occurred among inner-city Black people in the 1970s and 1980s, Case and Deaton now say. As low-skilled jobs vanished and families broke apart, Black victims of crack cocaine and the AIDS epidemic represented an early wave of deaths of despair. Even today, mortality rates for Black people still exceed those of white people in the United States for a variety of reasons, with Black overdose deaths on the rise over the last few years.

“The most meaningful dividing line [for being at risk of deaths of despair] is whether or not you have a four-year college degree,” Deaton says.

But despair has no clear scientific or medical definition. Psychiatric disorders plausibly related to a sense of despair, such as major depression and anxiety disorders, have been studied for decades. Despair — derived from a Latin term meaning “down from hope” — might be just another way to describe these conditions.

Or it might be its own special form of suffering. Some researchers regard despair as a distinct psychological status — one that can potentially be traced back to early childhood and may pose a risk for suicide, illegal drug use and maybe even physical pain.

For that reason, mental health clinicians need to work to distinguish despair from depression, even if despair isn’t a disorder in psychiatry’s diagnostic manual, says psychiatrist Ronald Pies of the State University of New York’s Upstate Medical University in Syracuse. “An overreliance on what is sometimes called ‘the Bible of psychiatry’ is likely to be misleading or inadequate when assessing the risk of suicide and illicit drug use,” he contends.

What’s more, recognizing and measuring despair, or something like it, as a state of mind separate from depressive disorders might shed light on the uptick in mental distress reported by people of all backgrounds during the coronavirus pandemic, Pies says. Developing a despair scale may also provide insights into those individuals most likely to succumb to despair-related fatalities. Long-term trends in national mortality data suggest that such deaths will continue to climb, even long after the viral calamity ends.

Downhearted minds

Case and Deaton’s emphasis on escalating 21st century deaths of despair — further detailed in their 2020 book Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism — hit a nerve, especially among researchers studying groups of children as they grow into adults. These developmental scientists are in a prime position to uncover the roots of deadly despair and identify how some individuals nurture hope during difficult times while others experience a toxic brew of mental pain.

First, though, despair must be defined in a measurable way. In a study in the June JAMA Network Open, researchers described a preliminary assessment of a tool that can be used to estimate an individual’s level of despair. To develop the tool, psychologist William Copeland of the University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine in Burlington and colleagues focused on youngsters living in mostly rural parts of western North Carolina, a section of Appalachia that has been devastated by opioid overdoses and other deaths of despair. Known as the Great Smoky Mountains Study, the research was launched in 1992 and has assessed mental health in 1,266 individuals as many as 12 times, from ages 9 to 13 up to age 30.

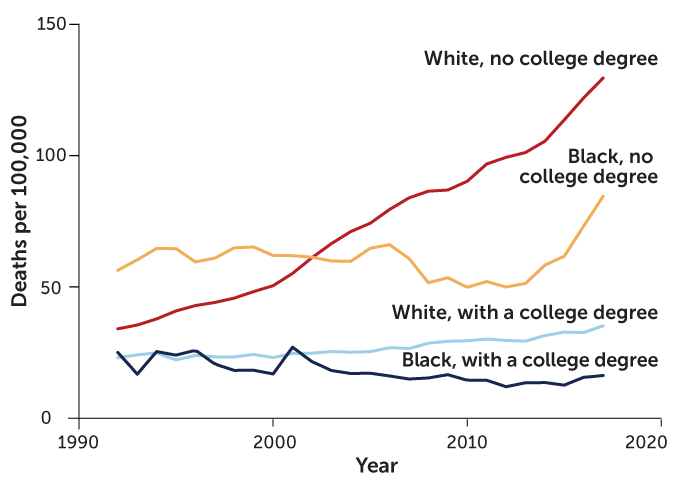

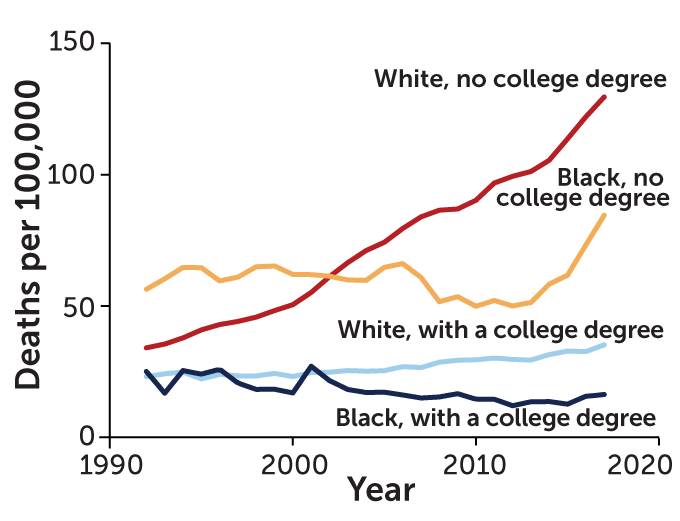

Rates of deaths of despair among middle-aged U.S. adults

An analysis of national data from 1992 to 2017 for adults ages 45 to 54 reveals an increasing risk of alcohol, drug and suicide mortality among those without college degrees, whether Black (orange line) or white (red line). For reasons that are not yet clear, Black college graduates (dark blue line) had the lowest rates of deaths of despair in this statistical comparison.

Source: A. Case and A. Deaton/Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism 2020

Inspired by Case and Deaton’s findings, Copeland’s team looked at how despair has been defined in recent scientific studies and then reexamined the North Carolina data from a new perspective, identifying seven indicators of despair.

Two indicators — feeling hopeless and having low self-esteem — are among the symptoms of persistent depressive disorder, a psychiatric condition consisting of a depressed mood that lasts for at least two years in adults. Another indicator — feeling unloved — is a symptom of major depression, a mental disorder characterized by bouts of overwhelming sadness and social isolation lasting at least two weeks. A fourth indicator — worrying frequently — contributes to what mental health clinicians call generalized anxiety disorder. The remaining three indicators — loneliness, helplessness and feeling sorry for oneself — are not symptoms of any psychiatric disorder.

Combining those seven indicators into a despair scale let the researchers compare levels of despair among youngsters. Between 1 and 5 percent of children and teens in the study experienced at least one symptom on the scale in the three months before being interviewed, Copeland’s group reported. Among 25- to 30-year-olds, about 20 percent reported one despair item, and 7.6 percent cited at least two despair items, in the previous three months. Few participants suffered from more than five of the seven despair indicators. Individuals who cited single despair items related to depression rarely qualified for a depressive disorder in psychiatry’s diagnostic manual.

Young adults’ despair scores were generally higher among people who didn’t get a college degree and among African Americans in general.

Overall, 25- to 30-year-olds became increasingly likely to think about or attempt suicide and to abuse illicit drugs, including opioids, as they scored higher on the despair scale. These trends were especially strong among participants who had elevated despair scores that traced back to childhood.

In contrast to Case and Deaton’s national findings indicating that alcoholism contributes to deaths of despair, despair scores among participants displayed no link with alcohol abuse. Alcoholism is more widespread than suicide and opioid abuse, suggesting that excessive alcohol drinking stems from a wider range of stressful situations and personal problems than the other two behaviors do, Copeland says. As a result, any influence of despair on alcohol abuse may be difficult to pick up statistically.

And though lower education levels were associated with higher despair scores, Copeland’s team failed to find an elevated tendency of less-educated participants to become suicidal or abuse drugs. That finding deserves closer scrutiny in a nationally representative sample of young adults, not just rural North Carolinians, Deaton says. Further research also needs to expand the current despair scale to include other potential indicators of despair, such as sadness, recklessness and declining immune function, Copeland adds.

Despair as measured by the new scale represents a downhearted state of mind, not a mental disorder, Copeland suspects. High despair scores predicted illicit drug abuse and suicidal thoughts and behaviors regardless of whether 25- to 30-year-olds qualified as depressed. Despair was not usually accompanied by depression, though depressed participants typically reported experiencing indicators of despair, such as being lonely.

Scores on this instrument highlight growing concerns that a sense of despair contributes to self-destructive but not necessarily lethal behavior among people on the cusp of adulthood. “We’re seeing a large effect of despair on [some] young adults,” Copeland says. “It makes their lives miserable.”

Big hurts

As for older adults, despair doesn’t just fuel deaths among less-educated Americans, it may also sucker-punch these people into a world of physical pain, a recent study from Case, Deaton and psychologist Arthur Stone of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles suggests.

By their own accounts, today’s midlife Americans in their 40s and 50s have already experienced more pain throughout life than today’s elderly Americans have over longer periods of time, the researchers report in the Oct. 6 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. And that trend has become increasingly pronounced over the last several decades among U.S. adults without college degrees. These findings come from four nationally representative samples and apply across racial and ethnic groups.

In samples of adults studied every year from 1997 to 2018, participants increasingly reported frequent and intense lower-back pain, the researchers found. Weight gain over that time statistically accounts for only about one-quarter of the reported rise in lower-back pain, the researchers say, and so can’t fully explain the pain.

In other wealthy countries, the prevalence of physical pain reported by adults without a college degree increased by 4 percent between those born in 1950 and those born in 1990. In the United States, the increase was 21 percent, an analysis of data on self-reported physical pain from several national and international surveys shows. Deaths of despair have also increased to a much greater extent in the United States than in other Western nations, the researchers say.

Like deaths of despair, reports of increasing pain by less-educated adults reflect a snowballing erosion of working-class life and rising levels of despair among those born after 1950, Case, Deaton and Stone speculate. In their new book, Case and Deaton present evidence for that argument based on trends in unemployment, losses of health insurance, out-of-wedlock births and other factors.

“The mind-body connection is incredibly important,” Case says. “Feeling excluded and socially isolated can trigger physical pain.”

Viral distress

Despair also deserves close scrutiny as an unfortunate consequence of the coronavirus pandemic, Pies says. No one doubts that emotional suffering has accompanied COVID-19. A U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention survey published August 14 found that U.S. adults reported substantially more symptoms of anxiety disorder and depressive disorder in June 2020 than in April through June 2019. Reported symptoms of stress and trauma, as well as thoughts about suicide, also rose this year. About 10 percent of 5,140 survey participants said that COVID-19 caused them to start or increase drug use.

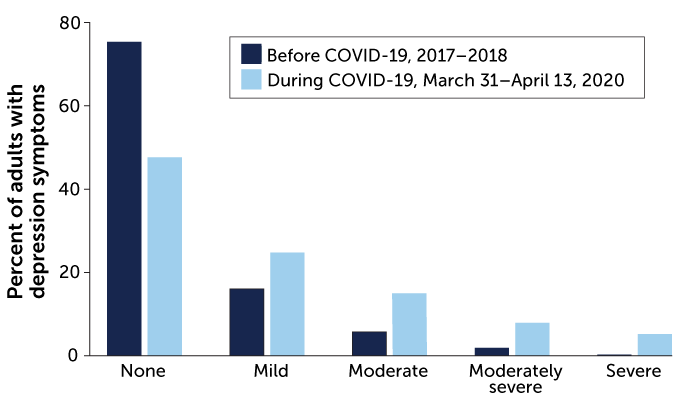

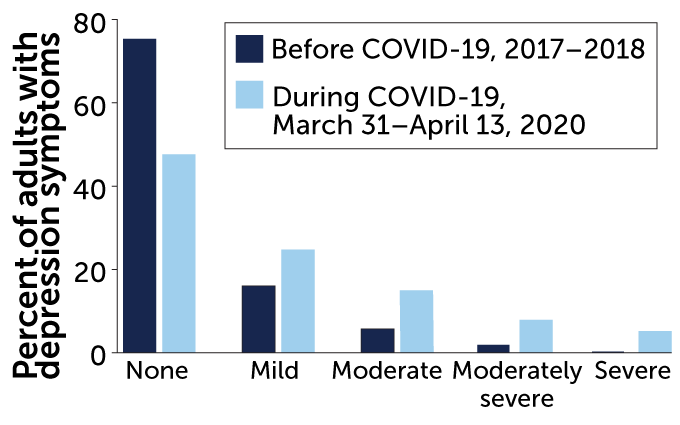

Another national survey conducted from March 31 through April 13 found that 27.8 percent of the U.S. adult population reported depression symptoms, compared with 8.5 percent of U.S. adults surveyed in 2017 and 2018. These survey results appear in the September JAMA Network Open.

Rates of depression symptoms in U.S. adults

Light-colored bars show a rise in mild to severe depression symptoms among U.S. adults as the coronavirus pandemic flared this year, relative to rates of depression symptoms before the pandemic (dark-colored bars).

Source: C.K. Ettman et al/JAMA Network Open 2020

But increased psychiatric symptoms during the pandemic don’t necessarily mean that more people are suffering from psychiatric disorders, Pies says. Self-reported anxiety and depression symptoms may not be long-lasting enough or impair daily functioning enough to be classed as mental disorders. And Copeland’s findings on despair suggest that it may be too simplistic to assume that the pandemic has led to a widespread outbreak of depression and other mental disorders, Pies says.

Instead, many emotional reactions to the pandemic detected in surveys may reflect understandable demoralization and grief at painful losses of jobs, social contacts and loved ones felled by the virus, Pies wrote August 24 in Psychiatric Times. Demoralization, he says, involves experiencing a loss of meaning and purpose in life, accompanied by frustration, anger and a feeling that one is fighting a losing battle. That definition partly overlaps with Copeland’s despair scale, Pies says. The extent to which demoralization and despair intersect is uncertain.

How despair, depression and the pandemic may overlap is still fuzzy. But what is clear is that deaths of despair can’t be blamed on mental disorders and can lead to real costs to society, Case and Deaton contend. And that won’t end with a vaccine. “Deaths of despair are a long-term phenomenon that will be with us after the COVID-19 crisis is over,” Case says.

Trustworthy journalism comes at a price.

Scientists and journalists share a core belief in questioning, observing and verifying to reach the truth. Science News reports on crucial research and discovery across science disciplines. We need your financial support to make it happen – every contribution makes a difference.