E-cigarettes proving to be a danger to teens

Vaping is more popular than smoking among young people

DANGERS OF VAPING E-cigarettes have surpassed cigarettes as the most commonly used tobacco product among teenagers. Medical researchers are sounding the alarm.

John Van Hasselt/Corbis

They’ve appeared on television and in magazines — Katy Perry, Johnny Depp and other celebrities vaping electronic cigarettes. The high-tech gadgets, marketed as a healthier alternative to traditional cigarettes, seem to be available everywhere, from Internet suppliers and specialty vaping shops to 24-hour convenience marts.

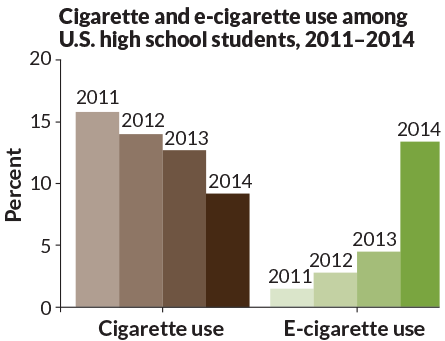

E-cigarettes have become the fashionable new electronic toy. With vape flavorings like bubble gum, Dr Pepper and cotton candy, teens have been taking the bait. In 2014, e-cigarettes surpassed cigarettes as the most commonly used tobacco product by middle school and high school students, according to an annual U.S. survey.

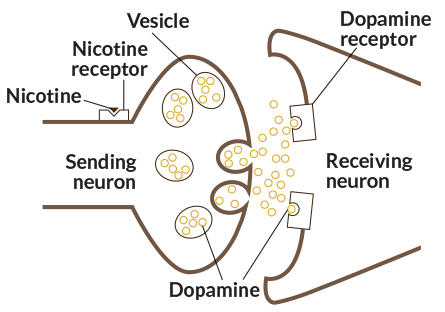

Teens’ fascination with this nicotine-dispensing smoking alternative worries physicians and toxicologists. Data from a growing number of studies indicate that electronic cigarettes are far from harmless. They also pose their own addiction risk.

Chemicals in e-cigarettes can damage lung tissue and reduce the lungs’ ability to keep germs and other harmful substances from entering the body, studies have found (SN: 12/27/14, p. 20). The flavored e-cig liquids can do their own damage. And the lungs — not to mention the young brain (see “Nico-teen brain,” below) — may be particularly vulnerable to nicotine’s effects.

“What I can say definitively is that nicotine is harmful to the developing teenage brain,” says Mitch Zeller, director of the Center for Tobacco Products at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in Silver Spring, Md. “No teenager, no young person, should be using any tobacco or nicotine-containing products.” E-cigarettes, he says, are among the products that should be kept firmly out of the hands — and mouths — of adolescents.

Soaring popularity

In the last year, e-cigarette use by U.S. teenagers tripled — from 4.5 to 13.4 percent among high school students and from 1.1 to 3.9 percent among middle schoolers, according to data from the annual National Youth Tobacco Surveys (sponsored by the FDA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Other surveys, some national, some state-level, offer even more troubling figures.

In some parts of the country, e-cigarette use by young people is especially high. In Hawaii, 29 percent of more than 1,900 ninth- and 10th-grade students in five schools had at some time used e-cigarettes, according to a survey published in Pediatrics in January.

And teen vaping is hardly restricted to Americans. A new survey of nearly 2,700 German seventh-graders finds that almost 5 percent have vaped. A May report in the Journal of Adolescent Health describes a near tripling in vaping among teens in New Zealand between 2012 and 2014. By 2014, one in five 14- to 15-year-olds there had given it a try. Reported use by high school teens in Poland is even higher: 23.5 percent.

Such trends, Zeller says, “should raise alarm bells for parents and educators.”

Smokeless nicotine

Unlike true cigarettes, electronic cigarettes don’t burn tobacco. They don’t burn anything. Instead, the battery-operated devices turn a flavored liquid into a vapor. Users inhale, or vape, the mist. The liquid usually contains nicotine, a natural stimulant in tobacco that is highly addictive. Also in the liquid are solvents, flavorings and who knows what else.

E-cigarettes first appeared in the U.S. market in 2007, designed to help tobacco addicts wean themselves from smoking. Recent research, however, indicates that vaping does not boost quit rates (SN Online: 3/24/14).

Irina Petrache of the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis studies the impact of nicotine in e-cigs. She and her colleagues recently exposed lung tissue in the lab to nicotine alone, to cigarette smoke or to e-cigarette vapors. Compared with tissues treated with a nicotine-free soluble extract, all three types of exposures caused lung cells to become more permeable. The cells were no longer an effective barrier to outside substances.

In follow-up tests, the researchers exposed lab animals to nicotine and e-cig liquids. These exposures caused increased oxidative stress and resulted in a buildup of inflammatory cells in the lungs of the mice. “We were surprised at how quickly we saw this inflammation,” she says. In fact, the affected lung surface cells “became activated” by the exposures, Petrache explains, “which means they became an active participant in the inflammation.”

Her team’s findings show that nicotine alone — independent of anything else in cigarette smoke or e-cig vapors — can harm lung tissue. While neither nicotine nor the vapors were quite as potent as the cigarette smoke, all three were triggers. “It took a somewhat larger amount of e-cigarette vapor or nicotine to cause the damage,” she explains. Her group reported its findings online May 15 in the American Journal of Physiology — Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology.

In an “unexpected and disturbing” result, Petrache’s team found that even an e-cigarette liquid with no nicotine can disrupt the barrier function of lung cells. Her group suspects this problem may have to do with soluble components, such as nicotine or the compound acrolein, in the flavored liquids that are inhaled through e-cigarettes. Despite a public perception to the contrary, vaping “does not seem to be harmless,” Petrache concludes.

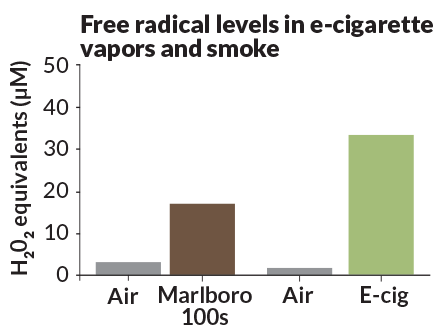

Irfan Rahman of the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York has a good idea of what was behind the inflammation witnessed by the Indiana team: free radicals spawned as the flavored e-cigarette liquids vaporized. Indeed, he was surprised to learn how potent a source of free radicals e-cigarettes can be. Free radicals, with one unpaired electron, can damage cells and derail the immune system (SN: 4/18/15, p. 9).

Rahman, a biochemist, and his team drew the vapors from e-cigarettes into sophisticated test equipment that his lab uses to measure free radicals. Some vaped puffs created from flavored e-liquids — with or without nicotine — produced high concentrations of free radicals. In fact, the nicotine-free vape liquid produced a substantially higher concentration of free radicals , Rahman’s team reported in February in PLOS ONE .In other experiments, Rahman’s team quantified the free radicals from vaping and smoking. Puffs from both contained free radicals aplenty; the quantity in each vaped puff exceeded those in a puff of cigarette smoke.

To further explore e-cigarette use, Rahman and students from his lab began frequenting vape shops and talking to the teens and young adults who had come to buy supplies. The vapers bragged about being able to use e-cigarettes indoors where smoking was banned, that e-cigs could cost far less than cigarettes and that their colors, potency and flavors could be personalized to deliver a truly “individual” experience.

Some vapers described how they customize the vaping experience by eliminating the cartridge of e-liquid, also known as “e-juice,” and using an eye dropper to drip a flavored solution directly onto the e-cigarette’s heating element. Then they breathe in the vapors that rise off the coils. This technique, called “dripping,” delivers a more potent hit of nicotine, users told Rahman. It also allows them to switch between flavors more easily — an advantage at parties and in groups where people share an e-cigarette.

Rahman and colleagues investigated how dripping might affect the vapor profile. They found that it upped production of free radicals dramatically.

Many teens and young adults told Rahman and colleagues that their throats became dry and scratchy with vaping. Some said that vaping made them cough or choke and that their mouths bled. Rahman says he decided, “We’ve got to start looking into these things and see what’s going on.”

So his team exposed human lung cells and mice to e-cigarette vapors. The vapors triggered intense inflammation in both. Preliminary data from Rahman’s team indicate that vaping can cause DNA damage in test tube–grown cells. More worrisome: In one of his team’s lung cancer cell lines, e-cigarette vapors triggered precancerous cells to act more like malignant cells. “They go from bad to worse,” Rahman says. Surprisingly, he says, cigarette smoke did not show this effect.

Studies by his group and others, Rahman says, suggest that vaping is not safer than smoking: “It’s equally bad.”

Weakened defenses

Last year in San Diego at a meeting of the American Thoracic Society, Laura Crotty Alexander reported that vaping can make it harder for the body to kill germs (SN: 6/28/14, p. 9). Crotty Alexander, a pulmonologist, works at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System.

In the lab, she exposed Staphylococcus aureus bacteria to e-cigarette vapors, hoping to create conditions that would somewhat mimic what the germs might encounter in the lungs of an e-cig user. The bacteria exposed to high levels of nicotine covered themselves with a thicker biofilm coating than normal, which bolstered their protection.

Crotty Alexander then allowed mice to breathe in air containing these vaping-exposed bacteria. By the next day, the mice had three times as many bacteria in their lungs as did mice exposed to normal Staph bacteria. Fighting off the germs exposed to e-cigarette vapors proved hard for the mice.

Inflamed lungs with an impaired barrier might help explain why more germs made it into the mice’s lungs. Thomas Sussan of the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health and colleagues found similar connections between vaping and immune dysfunction.

Sussan’s team tallied the free radicals from vaping, measuring 700 billion or so free radicals per puff (SN Online: 2/4/15). Then, as Rahman’s group had done, Sussan and collaborators pumped e-cig vapors into a shoebox-sized chamber. They placed mice in the box for 90 minutes, twice daily, over a two-week period to inhale those vapors.

Afterward, the animals’ lungs showed substantial signs of oxidative stress and inflammation. Compared with unexposed mice, the vaping mice had “a nearly 60 percent increase in inflammatory cells,” Sussan says. The influx of immune system macrophages in the airways was similar to what his group had seen in mice exposed to cigarette smoke.To test whether this lung damage affected immunity, Sussan’s team exposed some of the “vaped” animals to either flu virus or Streptococcus pneumonia bacteria. Normally, macrophages would gobble up and kill the pathogens. The vaped animals produced plenty of macrophages, but the scavenger cells didn’t do their job. The result: “defective bacterial clearance,” the researchers reported in February in PLOS ONE.

Similarly, mice that had breathed in e-cig vapors proved less able than nonvaping mice to fight off the flu virus. Some of the mice exposed to the e-cigarette vapors died. All nonvaping mice survived.

The emerging animal data show that “clearly, these e-cigarettes aren’t safe,” concludes Sussan, a toxicologist. In fact, he says, any vapers “who think they are not doing any harm are fooling themselves.”

The Wild West

A challenge to probing any risks associated with e-cigs is the lightning pace with which the vaping environment has been evolving. In January 2014, at least 466 brands of e-cigarettes were for sale, according to a recent Internet survey by researchers at the University of California, San Diego. Each brand had its own website. That same survey turned up 7,764 uniquely named flavored e-liquids, with hundreds of new flavors appearing each month.

Sussan calls the e-cig market “the Wild West.” Tests on one device or flavored liquid may not extrapolate to others being sold. Makers of e-liquids don’t have to list their ingredients and nicotine amounts. And when listed, they aren’t reliable, several studies have found. Few flavorings in the e-juices have been evaluated for risks to the lungs.

A few research teams are trying to get a handle on what’s out there. Researchers at Portland State University in Oregon recently purchased and analyzed 30 e-juices. “The levels of flavorings that we found in some of the fluids were high — sometimes as much as 4 percent of the material,” says chemist James Pankow. That was unexpected, he says. His team published its findings online April 15 in Tobacco Control.

Industrial safety guidelines recommend workplace inhalation limits for some of the chemicals his team found in vaping liquids. Examples include the aldehydes vanillin and benzaldehyde. Based on the quantities of some of these chemicals found in the e-juices, people who chronically vape could inhale amounts greater than those recommended for employees, Pankow notes.

In addition, he says, breathing something is very different from eating it. The gastrointestinal tract is better able than the lungs to tolerate incoming materials. Even the Flavor Extracts Manufacturers Association, he says, argues that it would be “false and misleading” to claim that food-grade flavorings are inherently safe to vape.

Certain other chemicals added to cigarettes to make them easier to smoke are found in e-cigs as well, a team at the Harvard School of Public Health reports. The researchers sifted through a mountain of tobacco company documents released to the public in the 1990s as part of a legal settlement.

“What we found,” says Hillel Alpert, “is that they added ingredients — particularly pyrazines — that appear to have contributed to the ‘smooth’ flavor, reducing the harshness of certain cigarettes.” Pyrazines are also being added to e-cigarette fluids, his team wrote online June 10 in Tobacco Control. Such chemicals may mask the body’s natural aversion to irritating aspects of vapors, making them easier to inhale. This might indirectly foster addiction, Alpert says. Simply put: Pyrazines can make it easier for teens to comfortably take in nicotine.

Arguing for regulations

Vaping products remain largely unregulated in the United States and elsewhere. The FDA announced in April 2014 that it plans to extend its regulation of tobacco products to include e-cigarettes. The agency has not yet acted on that proposal.

As of December 2014, in 10 states and the District of Columbia, children can legally buy e-cigs. And to buy them on the Internet, minors just have to claim they are adults.

On April 28, a broad consortium of 31 organizations — from the American Lung Association and American Academy of Pediatrics to the United Methodist Church — sent an open letter to President Obama asking him to light a fire under the FDA about regulation of e-cigarettes and other unregulated tobacco products. Without action, the groups charged, “there are no restrictions in place to protect public health against the risks these products pose, particularly to the health of our children.”

Editor’s note: This article appears in the July 11, 2015, Science News with the headline, “The Dangers of Vaping.”