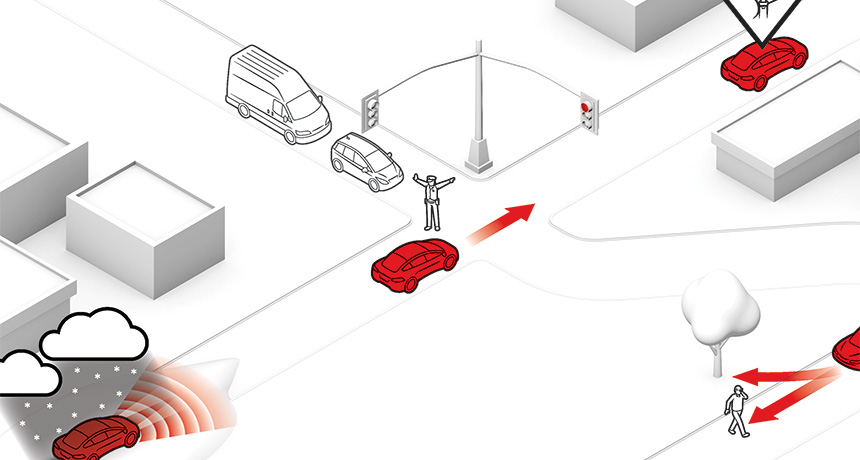

DRIVERLESS FUTURE Self-driving cars struggle when faced with variable environments or unpredictable situations. Cars that get maps, updates and other data from the cloud will also be vulnerable to hacking.

James Provost

Self-driving cars promise to transform roadways. There’d be fewer traffic accidents and jams, say proponents, and greater mobility for people who can’t operate a vehicle. The cars could fundamentally change the way we think about getting around.

The technology is already rolling onto American streets: Uber has introduced self-driving cabs in Pittsburgh and is experimenting with self-driving trucks for long-haul commercial deliveries. Google’s prototype vehicles are also roaming the roads. (In all these cases, though, human supervisors are along for the ride.) Automakers like Subaru, Toyota and Tesla are also including features such as automatic braking and guided steering on new cars.

“I don’t think the ‘self-driving car train’ can be stopped,” says Sebastian Thrun, who established and previously led Google’s self-driving car project.

But don’t sell your minivan just yet. Thrun estimates 15 years at least before self-driving cars outnumber conventional cars; others say longer. Technical and scientific experts have weighed in on what big roadblocks remain, and how research can overcome them.

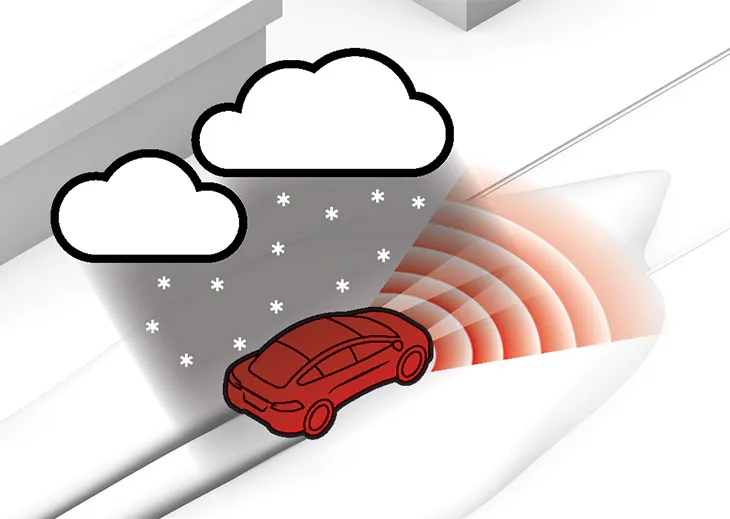

Sensing the surroundings

Sensors need to be reliable, compact and reasonably priced — and paired with detailed maps so a vehicle can make sense of what it sees.

Leonard is working with Toyota to help cars respond safely in variable environments, while others are using data from cars’ onboard cameras to create up-to-date maps. “Modern algorithms run on data,” he says. “It’s their fuel.”

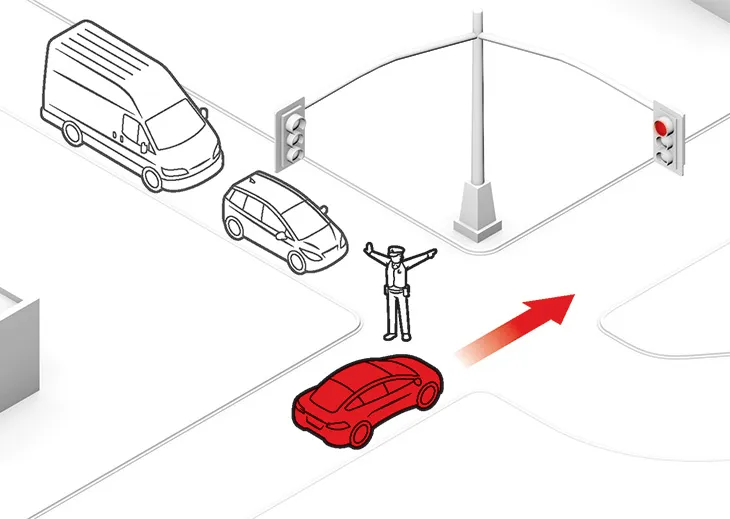

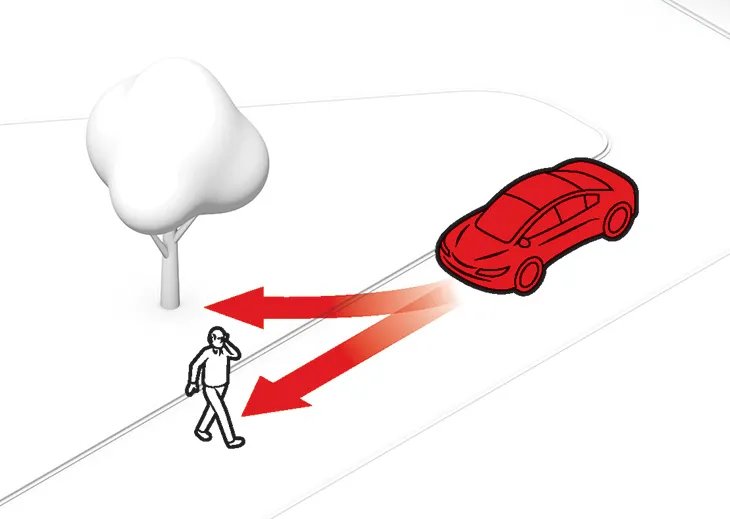

Unexpected encounters

Body language and other contextual clues help people navigate these situations, but it’s challenging for a computer to tell if, for example, a kid is about to dart into the road. The car “has to be able to abstract; that’s what artificial intelligence is all about,” Cummings says.

In a new approach, her team is investigating whether displays on the car can instead alert pedestrians to what the car is going to do. But results suggest walkers ignore the newfangled displays in favor of more old-fashioned cues — say, eyeballing the speed of the car.

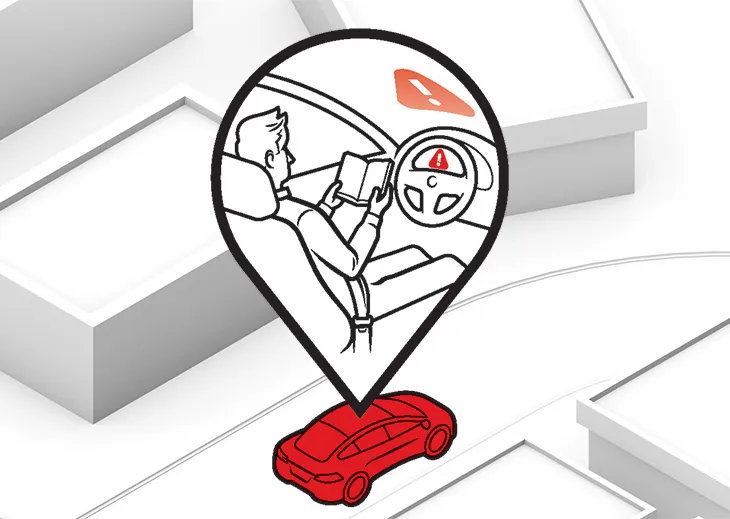

Human-robot interaction

“In a sense, you are still concentrating on some of the driving, but you are not really driving,” says Chris Janssen, a cognitive scientist at Utrecht University in the Netherlands.

His lab is studying how people direct their attention in these scenarios. One effort uses EEG machines to look at how people’s brains respond to an alert sound when the people are driving versus riding as a passive passenger (as they would in a self-driving car). Janssen is also interested in the best time to deliver instructions and how explicit the instructions should be.

Ethical dilemmas

In an online exercise called the Moral Machine, players choose whom to save in different scenarios. Does it matter if the pedestrian is an elderly woman? What if she is jaywalking? Society will need to decide what rules and regulations should govern self-driving cars. For the technology to catch on, decisions will have to incorporate moral judgments while still enticing consumers to embrace automation.

Cybersecurity

Self-driving cars, which would get updates and maps through the cloud, would be at even greater risk. “The more computing permeates into everyday objects, the harder it is going to be to keep track of the vulnerabilities,” says Sean Smith, a computer scientist at Dartmouth College.

And while terrorists might want to crash cars, Smith can imagine other nefarious acts: For instance, hackers could disable someone’s car and hold it for ransom until receiving a digital payment.