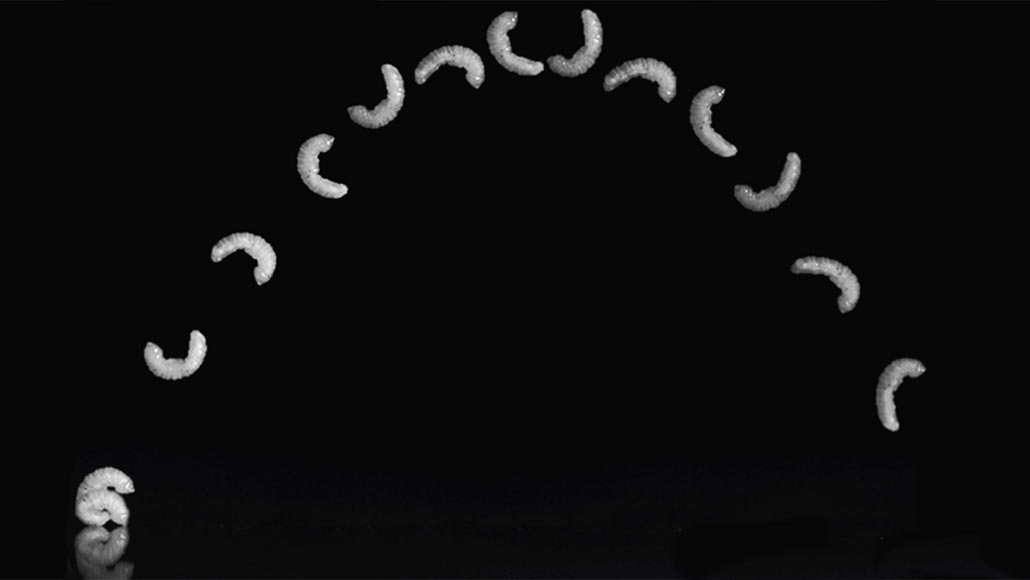

SPRING FLING Never mind about the absence of legs. A young gall midge, no bigger than a rice grain, can go airborne thanks to some clever latching.

G.M. FARLEY ET AL/JOURNAL OF EXPERIMENTAL BIOLOGY 2019

No legs? Not a problem. Some pudgy insect larvae can still jump up to 36 times their body length. Now high-speed video reveals how.

First, a legless, bright orange Asphondylia gall midge larva fastens its body into a fat, lopsided O by meshing together front and rear patches of microscopic fuzz. The rear part of the larva swells, and starts to straighten like a long, overinflating balloon. The fuzzy surfaces then pop apart. Then like a suddenly released spring, the larva flips up and away in an arc of somersaults, researchers report August 8 in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

In nature, something has to go wrong for this to happen, says evolutionary ecologist Michael Wise of Roanoke College in Salem, Va. These midges normally grow from egg to adult safely inside an abnormal growth, or gall, that they trick silverrod plants into forming. But as Wise was trying to coax out some still-immature larvae, he realized that the supposedly helpless young — extracted prematurely when they were no bigger than rice grains — could not only vault out of a lab dish but also could travel a fair distance across the lab floor.

To get a better look at the insects’ jumps, he contacted evolutionary biomechanist Sheila Patek at Duke University. “He sees small fast things and thinks of his buddy Sheila,” Patek says. Her lab specializes in resolving never-before-seen subtleties of animal motion, typically using high-speed video. “The truth is, we film for people all the time, and it’s almost never small and fast by our standards,” she says. “But this actually was.”

The larval jumps filmed were too great for a tiny larva’s muscles, Wise, Patek and colleagues concluded. Blobby little larvae were flipping themselves around with power equal to, or greater than, the oomph of high-power vertebrate flight muscles.

For small animals with constraints on muscles, “it actually works better to put energy into a spring,” Patek says. Small creatures can load energy into the spring gradually until whatever is latching the spring slips off. Then, the suddenly freed spring powers extreme motion.

Microscope images revealed hairlike structures on the larval surfaces that touched, suggesting that the tiny projections might stick together as type of latch. Such structures could inspire new types of adhesives, Patek says.

Patek had first recognized the latch-and-spring system in mantis shrimp, which throw punches so furiously they can smash aquarium walls, and then in a trap-jaw ant with killer jaws that spring shut in an instant. Those look not at all like the pliable little larvae, but Patek sees latches releasing springs. “My guess is they’re everywhere,” she says.

Still “latch systems are quite hard to study,” says coauthor Greg Sutton of the University of Lincoln in England, where he investigates the mechanics of insect moves. “We don’t know where the flea latch is,” for example, he says. The gall midge ends up with arguably the most clearly described system: the “smoking gun latch,” he calls it.

Details aside, tiny animals aren’t the only creatures using latches for fast moves, says Simon Poppinga of the Botanic Garden of the University of Freiburg in Germany, who wasn’t involved in the research. He studies the biomechanics of plants, which don’t grow muscles at all but have ways of moving fast. U.S. researchers have found that sphagnum moss fires “spore cannons,” capsules that deform as they dry and then suddenly crack open to launch spores at 16 meters per second that puff into miniature mushroom clouds (SN: 7/23/10, p. 8).

Poppinga and colleagues recently showed that Chinese witch hazel trees build up forces in the mature fruit that suddenly shoot out a seed rotating a bit like a bullet from a rifle. Unlike gall midge launches, though, these tree latches break when they let go. The leap of a legless seed is fast and dramatic, but it’s not repeatable.