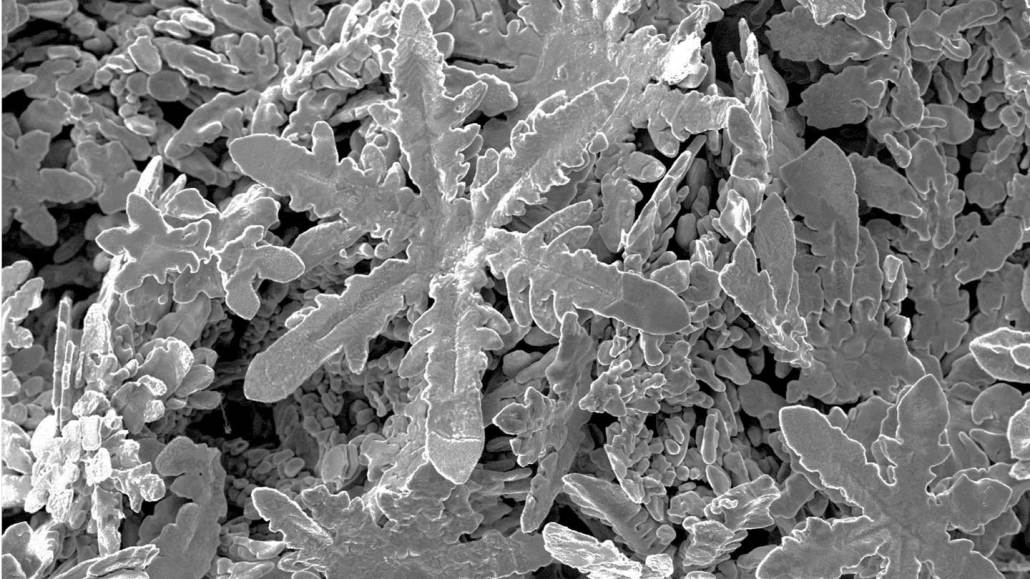

After heating a gallium-zinc alloy to 350° C and letting it cool for 10 days, a variety of zinc snowflake shapes crystallized in the liquid gallium.

S.A. Idrus-Saidi et al/Science 2022

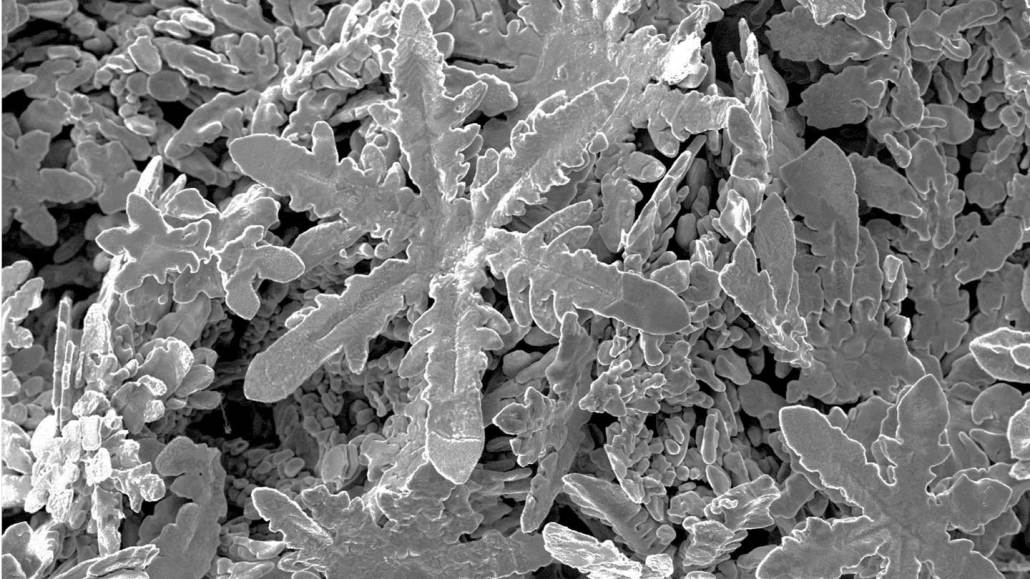

After heating a gallium-zinc alloy to 350° C and letting it cool for 10 days, a variety of zinc snowflake shapes crystallized in the liquid gallium.

S.A. Idrus-Saidi et al/Science 2022