Human fossils tell a fish tale

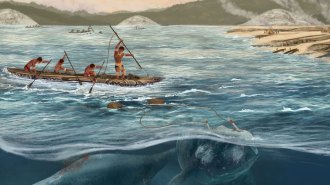

As Europe’s Stone Age began to wind down 30,000 years ago, Homo sapiens developed a taste for fish and waterfowl that Neandertals apparently couldn’t fathom. The move to such nouveau cuisine helped seal the evolutionary fates of these two groups, according to a report in the May 22 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

An analysis of fossil bones shows that early humans, who at that time were making rapid cultural advances, ate aquatic as well as land animals. In contrast, Neandertals, who died out in that period, were largely red-meat eaters.

The researchers, led by anthropologist Michael P. Richards of the University of Bradford in England, measured the concentrations of certain forms of carbon and nitrogen in fossils. The team studied nine H. sapiens individuals who lived in Europe between 28,000 and 20,000 years ago and five European Neandertals ranging in age from more than 100,000 years to 28,000 years. The chemical data reflect the amount of protein an individual consumed from distinct habitats, such as freshwater wetlands and dry, inland areas.

Related evidence indicates that Stone Age humans, unlike Neandertals, pursued small game that maintained their numbers in the face of intensive hunting (SN: 2/5/00, p. 85).

A varied diet gave H. sapiens an evolutionary advantage over Neandertals, especially as European populations expanded in the late Stone Age, the scientists conclude.