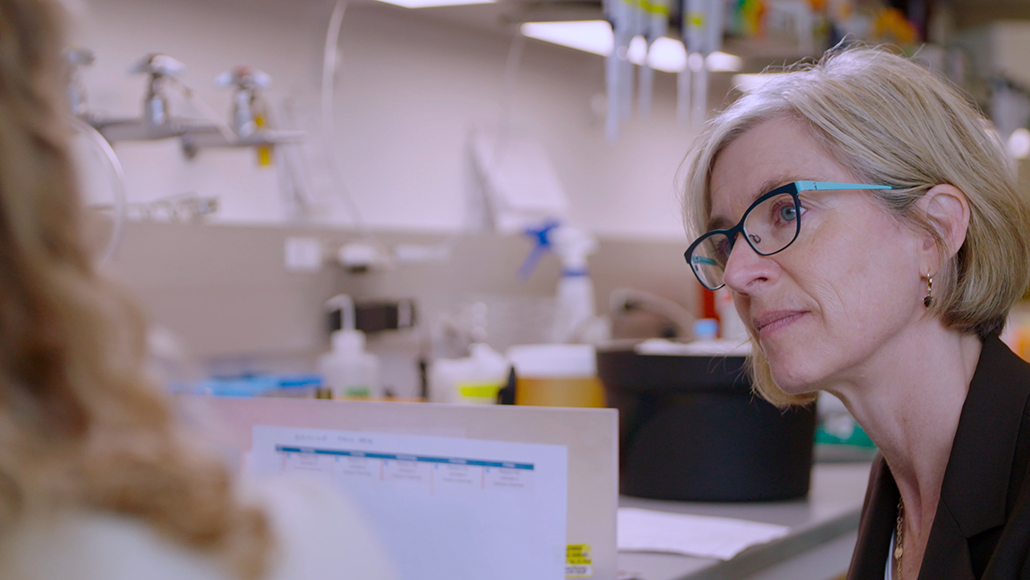

Jennifer Doudna, one of the first researchers to develop CRISPR as a gene-editing tool, is interviewed in Human Nature.

COURTESY OF GREENWICH ENTERTAINMENT

Humans have been tinkering with the genes of plants and animals through selective breeding for millennia. But the ability to change our own DNA is something very new.

The gene-editing tool CRISPR offers the promise of correcting genetic typos that cause a range of diseases. The documentary Human Nature — which opened in select U.S. cities on March 13, with more to follow — introduces viewers to the technology. Graphics, archival footage and beautiful imagery help explain how scientists took a DNA-cutting enzyme and its guide molecule, which form the basis of bacterial immune systems, and transformed them into CRISPR/Cas9, often just called CRISPR. Pioneers of the technology, including Jennifer Doudna, Feng Zhang, George Church and Emmanuelle Charpentier, recount serendipitous discoveries and hard-won insights in the tale of CRISPR’s development over several decades.

Human Nature

Opens in limited U.S. release on March 13

Wonder Collaborative

At the heart of the film is an ethical discussion of whether to allow scientists to use CRISPR to make changes in eggs, sperm or embryos that could be inherited by future generations. In one scene, Russian President Vladimir Putin tells a group of young people that using CRISPR to make designer people could be more dangerous than the nuclear bomb. In a counterpoint, bioethicist Alta Charo of the University of Wisconsin Law School in Madison says such fears may be overblown.

The film is wide-ranging, but with a few glaring omissions. Most notably, in 2018, Chinese researcher Jiankui He announced that human babies had been born from CRISPR-edited embryos (SN: 12/22/18 & 1/5/19, p. 20). That announcement touched off a firestorm of controversy and debates among scientists about whether a self-imposed moratorium on heritable editing should be enacted. In December 2019, He was sentenced to three years in prison for forging documents to make it look as if he had approval from an ethics review board to do the work. The film’s only reference to the event is a title card at the end that briefly lays out what happened and states, “It marked the first time in history that humans edited the genetic code of a future generation. This controversial experiment has intensified the global debate about where we, as a species, should draw the line.”

He’s announcement came as filming for Human Nature was wrapping up. It was too late “to add anything substantive” that would capture all the nuances of the case, says the film’s director, Adam Bolt. The Chinese researcher’s medical ethics violations might also have detracted from the film’s exploration of whether to allow heritable editing in general, Bolt says. “We really wanted to make this film about the larger debate of ‘should we do this.’ ”

Sign up for our newsletter

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.

The film also glosses over some potential environmental impacts. The idea of bringing back extinct animals (complete with a clip from Jurassic Park) is discussed. But the concept of gene drives, which has more immediate implications, is overlooked. Scientists envision using gene drives — a self-replicating, cut-and-paste version of CRISPR — to eliminate malaria-carrying mosquitoes or remove invasive species, for example. But by introducing harmful genes into wild organisms, gene drives have the potential to send entire species to extinction (SN: 10/27/18, p. 6). Granted, gene drives are hard to explain, but they deserve a mention.

Overall, Human Nature gets the science right, but its explanation of how CRISPR works is incomplete and may be misleading. The film shows an application of CRISPR that involves cutting out DNA containing a mutation and then pasting in a healthy copy of the gene. CRISPR theoretically could work that way, but in practice scientists have had trouble with this method. Instead, when CRISPR makes a cut, the ends of the cut DNA strands usually are haphazardly glued back together, making a mutation that can break a gene. That may not sound useful, but it is the basis for some possible treatments for genetic diseases (SN: 8/31/19, p. 6).

Human Nature is a good introduction for those wondering what the fuss over CRISPR is about. No film can capture the full breadth of the tool’s reach. But by avoiding CRISPR babies, gene drives or even some of the challenges of treating diseases, the film paints a rosier picture than is warranted. Those topics deserve a sequel.