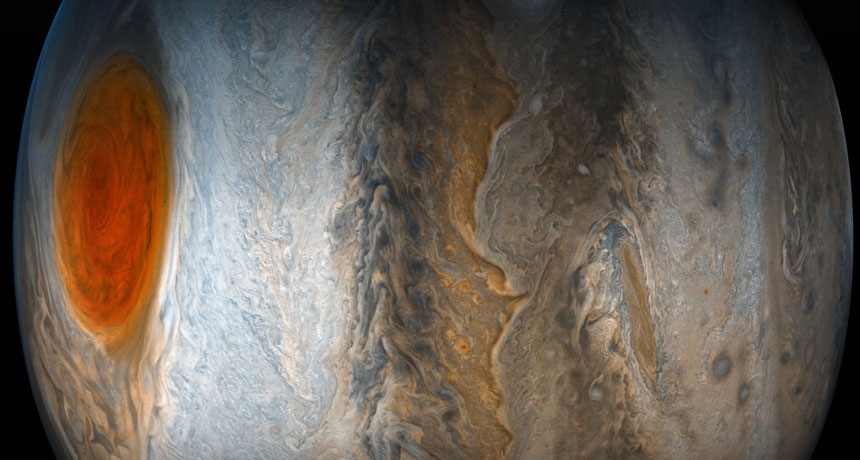

Jupiter’s massive Great Red Spot is at least 350 kilometers deep

NASA’s Juno spacecraft has measured the storm’s depth for the first time

HIDDEN DEPTHS Jupiter’s Great Red Spot (left in this image from NASA’s Juno spacecraft) extends down into the planet’s atmosphere at least 350 kilometers, as far as Juno can see.

Seán Doran, Gerald Eichstädt, MSSS, SwRI, JPL-Caltech/NASA