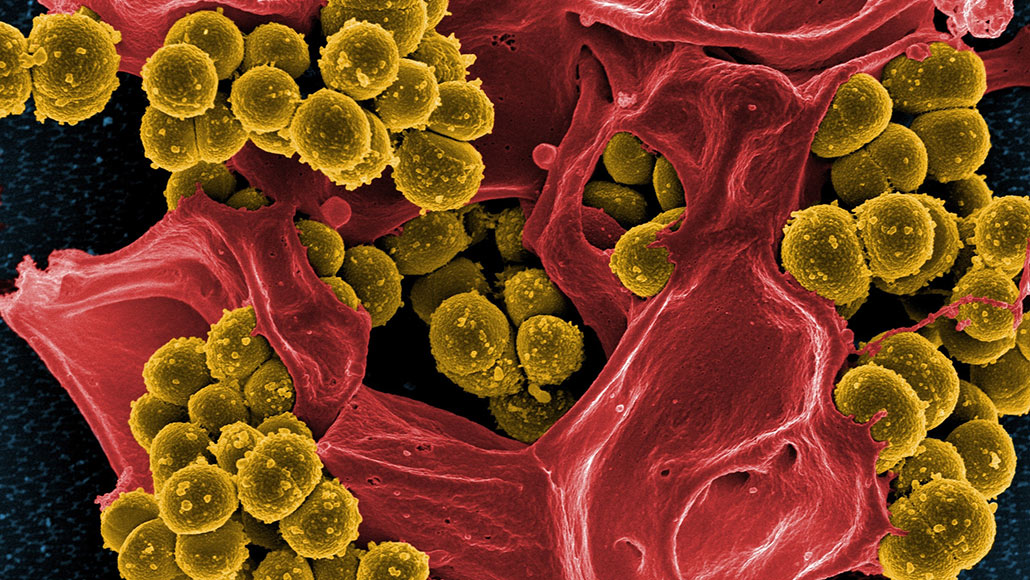

Being tolerant to at least one type of antibiotic helps deadly methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA, bacteria (yellow in this scanning electron micrograph) more easily develop resistance to another antibiotic.

NIAID

Infectious bacteria that are down but not quite dead yet may be more dangerous than previously thought. Even as one antibiotic causes the bacteria to go dormant, the microbes may more easily develop resistance to another drug, according to new research.

Deadly Staphylococcus aureus bacteria that could tolerate one type of antibiotic developed resistance to a second antibiotic nearly three times faster than fully susceptible bacteria did, researchers report in the Jan. 10 Science. The findings could suggest why drug cocktails used to knock out infections quickly sometimes fail, and may eventually lead to changes in the way antibiotics are prescribed in certain situations.

“Tolerance is not as well-known or as well-publicized [as resistance], but [this] work shows it is extremely important,” says Allison Lopatkin, a computational biologist at Barnard College in New York City, who was not involved in the study. “It is very much happening, and we need to pay closer attention to it.”

Antibiotic-tolerant bacteria stop growing in the presence of antibiotics, entering a sort of dormant state that helps the microbes weather the drugs’ assault for longer than usual. “They’re just putting their heads down,” says Nathalie Balaban, a biophysicist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Tolerant microbes aren’t capable of overcoming or counteracting antibiotics in the way that resistant organisms do. The microbes eventually die if exposure to the antibiotic continues at a killing dose, and if resistance doesn’t pop up.

Such tolerant bacteria may be the source of lingering or recurring infections and especially affect people with weakened immune systems or those with medical implants, such as joint replacements. Doctors may try giving drug cocktails to turn the tide of this sort of infection, particularly for hard-to-kill tuberculosis (SN: 8/16/19).

In previous lab experiments, Balaban and colleagues found that tolerant bacteria were more likely to develop antibiotic resistance. This happens in patients, too, the new study finds.

Doctors used the powerful antibiotic vancomycin to treat two patients who were admitted between May 2017 and May 2018 to Shaare Zedek Hospital in Jerusalem with methicillin-resistant S. aureus, or MRSA, infections in their bloodstreams. Within days, the patients’ bacteria became tolerant to the drug.

One patient, a 63-year-old woman with a recently implanted heart defibrillator, was switched to the antibiotic daptomycin. It turns out that her bacteria were also tolerant to that drug. So rifampicin was added to the mix. That antibiotic is often held in reserve, because, while potent, it has side effects and microbes often develop resistance to it quickly, says Andrew Berti, a pharmacist at Wayne State University in Detroit, who cowrote a commentary on the study in the same issue of Science.

The patient’s bacteria quickly became resistant to rifampicin. In lab experiments, it took just seven cycles of treatment with rifampicin for the woman’s daptomycin- and vancomycin-tolerant bacteria to develop rifampicin resistance. In comparison, it took 20 cycles for nontolerant bacteria to develop resistance. Similarly, the other patient’s infection developed tolerance before resistance.

Researchers got similar results in lab experiments with E. coli bacteria treated with several different drug combinations. That probably indicates that tolerance can lead to resistance in a wide variety of bacteria, says Jan Michiels, a microbiologist at VIB-KU Leuven Center for Microbiology in Belgium. “It’s quite a generic effect both in terms of species of bacteria and for classes of antibiotics,” he says.

Balaban thinks it might be useful to start patients on multidrug cocktails immediately to head off both tolerance and resistance. She and colleagues are working with doctors at hospitals to develop guidelines for giving antibiotics that take both tolerance and a patient’s immune system into account.

But severe side effects, drug costs and other factors make it unlikely that antibiotic cocktails will become doctors’ first go-to, Berti says. Clinical labs also currently don’t have good ways to identify tolerant bacteria, or know how to combat them when they arise, says his commentary coauthor Elizabeth Hirsch, an infectious disease pharmacist at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

Bacteria can develop tolerance in many ways (SN: 5/28/19), and scientists don’t yet know about all of them. “This highlights the importance of tolerance research,” says Etthel Windels, a microbiologist in Michiels’ lab. The more researchers know about the genes and mechanisms involved in tolerance, the better they can design tests for tolerant bacteria and ways to wake the organisms up and kill them.