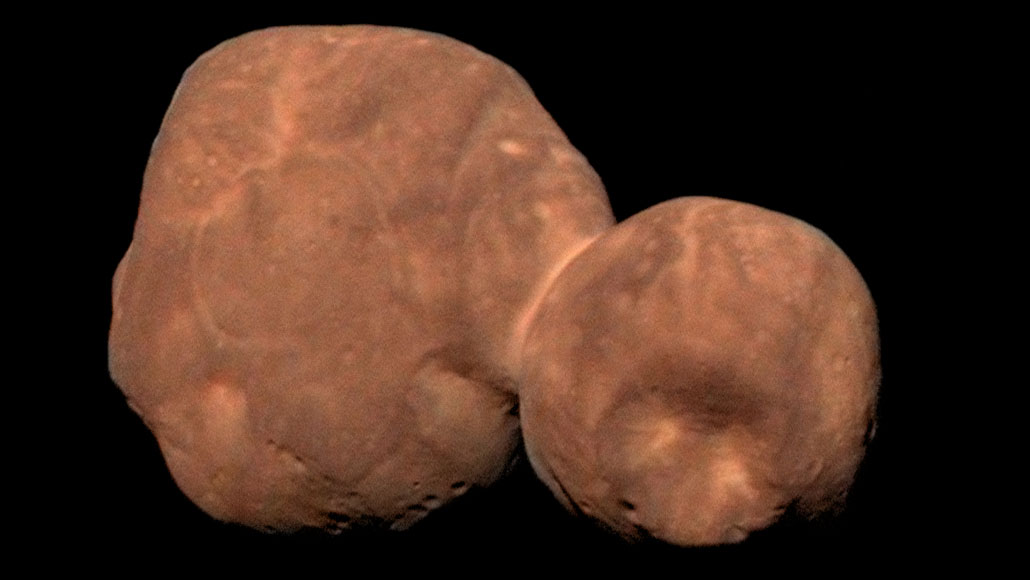

Arrokoth appears as a ruddy deformed snowman in this composite image acquired by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft as it sped past on January 1, 2019.

NASA, Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, Southwest Research Institute, Roman Tkachenko