A once-scrapped Alzheimer’s drug may work after all, new analyses suggest

At the highest doses, aducanumab slowed mental decline, the drug developer claims

By targeting sticky globs of amyloid (red) in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s, a new drug may offer a way to slow the disease’s spread.

Martin M. Rotker/Science Source

Call it a comeback — maybe. After being shelved earlier this year for lackluster preliminary results, a drug designed to slow Alzheimer’s progression is showing new signs of life. A more in-depth look at the data from two clinical trials suggests that patients on the biggest doses of the drug, called aducanumab, may indeed benefit, the company reported December 5.

People who took the highest amounts of the drug declined about 30 percent less, as measured by a commonly used Alzheimer’s scale, than people who took a placebo, Samantha Haeberlein of the biotechnology company Biogen reported at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease meeting in San Diego. With these encouraging results in hand, Biogen, based in Cambridge, Mass., plans to seek drug approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in early 2020.

The results are “exhilarating, not just to the scientific community but our patients as well,” Sharon Cohen, a behavioral neurologist at the Toronto Memory Program, said during a panel discussion at the meeting. Cohen participated in the clinical trials and has received funding from Biogen.

The presentation marks “an important moment for the Alzheimer’s field,” says Rebecca Edelmayer, director of scientific engagement for the Alzheimer’s Association in Chicago. Alzheimer’s disease slowly kills cells in the brain, gradually erasing people’s abilities to remember, navigate and think clearly. Current Alzheimer’s medicines can hold off symptoms temporarily, but don’t fight the underlying brain destruction. A treatment that could actually slow or even stop the damage would have a “huge impact for patients and their caregivers,” she says.

If confirmed, the results also bolster the idea that the build-up of amyloid, a sticky protein that accumulates in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s, is a key early step of the disease, as opposed to a red herring, as some have argued (SN: 2/25/11).

Aducanumab is an antibody designed to target both small clusters and larger clumps of amyloid, called fibrils, for removal. But the drug has had a roller coaster history. Early on, the drug was shown to clear amyloid from the brain (SN: 8/31/16). Researchers launched two phase III trials, designed to prove a drug’s worth by pitting it against standard treatments or a placebo,that enrolled people around age 70 who showed early signs of Alzheimer’s. Preliminary data from those two trials showed that the drug was unlikely to hit its goals of slowing symptoms along with the underlying brain signs of the disease more than a placebo treatment.

Those lackluster findings led Biogen to stop the trials in March before they were finished.

But then in October, after rolling in three more months of data that became available after the initial analyses, Biogen decided that the drug showed promise after all, particularly among people who received the highest dose, which was 10 milligrams of the drug per kilogram of body weight. The company had decided midway through the trial to increase the doses of some people who had previously been assigned to lower doses for fear of side effects.

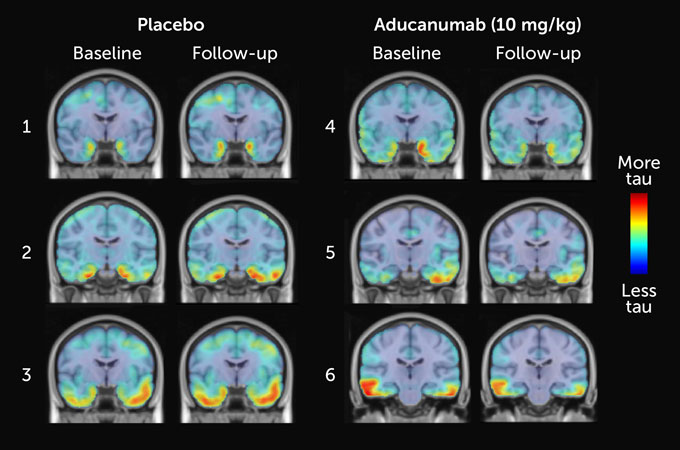

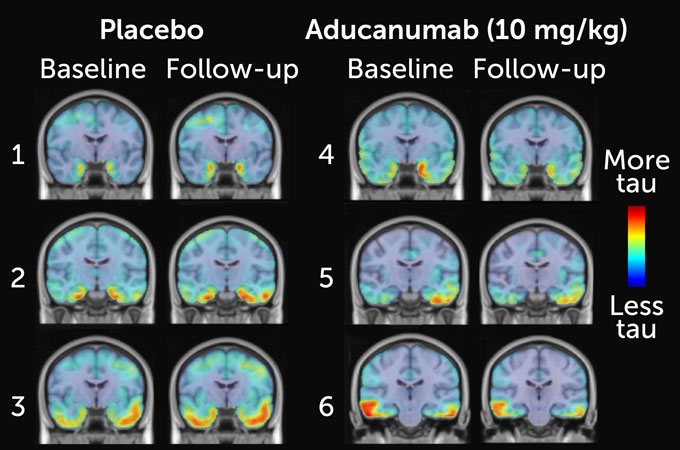

Updated results included a total of 3,285 people who had early signs of cognitive slipping. Surveys measured participants’ abilities on six aspects of life, including memory, orientation, personal care and problem solving. Analyses on a subset of 288 people in one trial who received the highest dose showed that, while they still lost some mental abilities over the year and a half of the study, they declined 30 percent less than those who received the placebo. A similar subset of 282 people in the other trial declined 27 percent less than those who took a placebo. Brain scans showed that, compared with people on the placebo, the brains of people taking aducanumab had less amyloid — and less tau, another protein associated with Alzheimer’s. Both the tau and amyloid results indicate that the drug was in fact slowing the disease.

Tangles thwarted

People who received placebo had more tangles of a protein called tau (red) in certain parts of their brain than people who received the drug aducanumab, a small analysis finds. Shown are three representative brain scans of people who received placebo (left) and people who received the highest dose of aducanumab (right).

Progression of tau tangles in individual patients’ brains, by treatment

The treatment did cause some side effects. Around 40 percent of the people who received the highest dose of aducanumab showed signs of brain swelling or bleeding, brain scans revealed. Most didn’t exhibit any symptoms of those problems, though.

The extent of improvement seen in these results, particularly on measurements of day-to-day abilities, is “a big deal,” Cohen says. “Those of us who know this disease well know what it means to lose yourself slice by slice. Anything you can hang onto, and do well, is a triumph.”

Two major changes to the trials — the change in dosing midway through and the trials’ early ends — complicate the analyses. Those complexities, and the whiplash they have caused, has left some researchers wary of the newest results.

Neurologist Samuel Gandy, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, is withholding judgement until more data is available. Biogen ought to share its data with other scientists for independent analyses, which is what happened with a different Alzheimer’s drug called solanezumab, he says. “This complete open sharing is now the gold standard, and is especially important for aducanumab, where there now exists such controversy,” he says.