Overdose deaths tied to antianxiety drugs like Xanax continue to rise

Many fatalities involving benzodiazepines also involve opioids

SERENITY PILL Benzodiazepines, such as Valium and Xanax, are widely prescribed to treat anxiety and insomnia. Also highly addictive, the drugs are involved in more and more overdose deaths.

Dean812/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

As public health officials tackle opioid addiction and overdoses, another class of prescription drugs has been contributing to a growing number of deaths across the United States.

Benzodiazepines, such as Valium and Xanax, are commonly prescribed for anxiety and insomnia. The drugs are also highly addictive and can be fatal, especially when combined with alcohol or opioids. In the latest sign of the drug’s impact, the number of overdose deaths involving “benzos” rose from 0.54 per 100,000 in 1999 to 5.02 per 100,000 in 2017 among women aged 30 to 64, researchers report January 11 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. That’s a spike of 830 percent, surpassed only by increases seen in overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids or heroin.

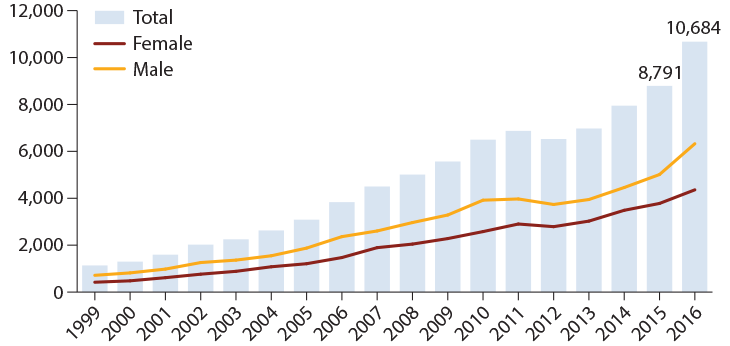

Overall, there were 10,684 overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines in the United States in 2016, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. In 1999, the total was 1,135.

Benzodiazepines have a sedating effect, and are particularly dangerous when used with other drugs that slow breathing, such as opioids and alcohol. In combination, the substances can “cause people to fall asleep and essentially never wake up again,” says Anna Lembke, an addiction psychiatrist at Stanford University School of Medicine. Benzos and opioids are often prescribed together, and opioids contribute to 75 percent of overdose deaths involving benzos.

The rising number of deaths involving benzos hasn’t stopped the flow of prescriptions. The number of U.S. adults who filled a prescription for benzos rose from 8.1 million in 1996 to 13.5 million in 2013, a jump of 67 percent, a study in the American Journal of Public Health in 2016 found. The quantity of benzos acquired more than tripled over the same time.

Increasing deaths

The number of overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines has gone up from 1999 to 2016, now reaching close to 11,000. Deaths among men and women are both on the rise.Number of U.S. overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines, 1999–2016

Benzodiazepines work by enhancing the activity of a chemical messenger in the brain that has a calming effect. The drugs help to distribute this neutrotransmitter, called gamma-aminobutyric acid, more widely in the brain. The drugs also work quickly, bringing fast relief.

Benzos are relatively safe for intermittent use over a few weeks. But with daily, long-term use the brain adapts to the drugs. As a result, they become less effective at relieving symptoms, and a person “needs more and more to get the same effect,” Lembke says. “It’s really easy to get people on these drugs, and hard to get them off again.”

Many of those who take the drugs aren’t using them properly, according to a study published online in Psychiatric Services in 2018. Of 30.6 million adults who reported using benzodiazepines, 5.3 million acknowledged misuse, such as taking benzos without a prescription or in a way not approved by a doctor.

National efforts to combat the opioid crisis should also target benzodiazepines, to reduce overprescribing and to educate doctors and patients about the drugs’ risks, Lembke and colleagues wrote in a February 2018 commentary in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Safer treatments for anxiety and insomnia are available, including antidepressants called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and therapies to change behaviors and learn coping strategies. Lembke says that benzodiazepines are more appropriate for short duration, low-dose treatment in severe circumstances, such as for seizures. That’s “how the evidence supports their use.”