Phone apps are helping scientists track suicidal thoughts in real time

Studies aim to find out if such close monitoring could help prevent suicides

PRECIOUS TIME Investigations that equip volunteers with smartphones indicate that suicidal thoughts fluctuate in signature ways over just a few hours. Closer scrutiny of these thinking patterns may lead to advances in suicide prevention.

Blue Planet Studio/Shutterstock

Suicide research is undergoing a timing shift, and not a moment too soon. A new breed of studies that track daily — and even hourly — changes in suicidal thinking is providing intriguing, although still preliminary, insights into how to identify those on the verge of trying to kill themselves.

Monitoring ways in which suicidal thoughts wax and wane over brief time periods, it turns out, can potentially strengthen suicide prevention strategies.

Digital technology has made these investigations possible. Smartphone applications alert people to report on suicidal thoughts as they arise in real-world settings. Scientists have traditionally been limited to tracking suicidal thinking over intervals of weeks, months and years, often in research labs and hospitals.

But risk factors that do a decent job of predicting the emergence of suicidal thoughts and acts over the long haul, such as persistent feelings of hopelessness, provide little help in tagging those who will become suicidal in the coming hours and days. Depression, often cited as a main driver of suicide, displays a strong link to suicidal thoughts but not to attempting or completing suicide in the near future.

Despite increasing efforts to combat suicide, U.S. suicide rates steadily rose from 1999 to 2016 (SN Online: 6/7/18). After declining during the 1990s, U.S. suicide rates now roughly equal those of 100 years ago. In recent weeks, the surprising high-profile suicides of designer Kate Spade and chef and television star Anthony Bourdain have attracted more attention to this problem.

“The field of suicide research needs to move away from its obsession with long-term risk studies,” says psychologist David Klonsky of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. A better understanding of how particular suicidal thoughts play out in daily life will lead to the identification of the most telling warning signs of impending suicide attempts, Klonsky predicts. Current theories focus on a range of potential factors that transform suicidal thoughts into life-ending actions, including feeling like a burden to others and suffering from unrelenting pain and hopelessness (SN: 1/9/16, p. 22).

Researchers can’t yet pinpoint suicide alarms for specific groups of people. That makes it even more vital for people contemplating suicide to contact suicide hotlines, psychotherapists and friends for help, Klonsky says. (To reach the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, call 1-800-273-TALK (8255).)

The rise of real-time, digital monitoring holds promise for giving clinicians a heads-up as to who is in the most immediate danger of acting on suicidal thoughts. A handful of studies published since 2009 have found that thoughts of suicide often appear rapidly in individuals with past suicide attempts, and can vary dramatically from hour to hour.

A team led by psychologist Evan Kleiman of Harvard University has taken digital monitoring a step further. The researchers recruited 51 adults from online forums related to suicide and self-harm and 32 adults hospitalized at a Boston psychiatric facility for recent suicide attempts or severe suicidal thoughts. Volunteers carried smartphones that prompted them four times daily, between four and eight hours apart, to rate the intensity of their current desire to kill themselves, their intention to carry out the act and their ability to resist suicidal urges. Those in the online group provided responses for 28 consecutive days. Hospitalized participants provided responses until they were discharged, a period that typically lasted one to two weeks.

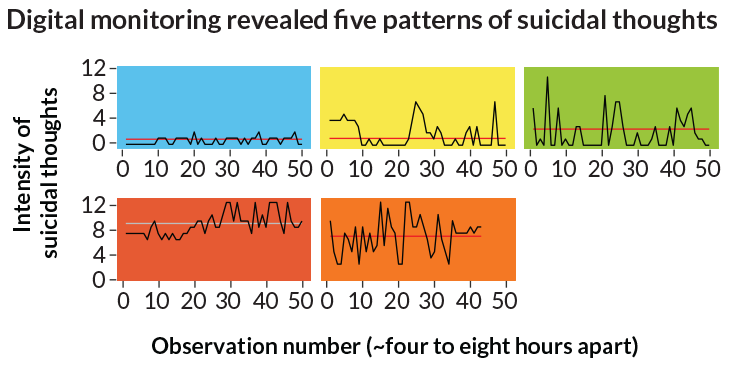

The same five patterns of suicidal thinking appeared in both groups, Kleiman’s team reports in a paper scheduled for publication later this year in Depression and Anxiety. One of those profiles may be associated with the greatest risk for trying to kill oneself in the future, the researchers say.

Ups and downs

Among people with past-year suicide attempts, smartphone-assisted ratings of the intensity of suicidal thoughts every four to eight hours displayed five patterns, a new study finds. Patterns consisted of low average intensity (red line) that was relatively stable (blue box), low average intensity that varied a lot (yellow), moderate average intensity that varied a lot (green), high average intensity that didn’t change much (red) and high average intensity that varied a lot (orange). Suicide tries in the month before the study clustered among those reporting severe suicidal thoughts with few fluctuations (red box).

Some individuals reported, on average, low levels of suicidal thoughts that either stayed constant, varied moderately or fluctuated greatly throughout the day. Others reported severe suicidal thoughts that varied either a little or a lot from one report to the next.

Among past-year attempters, suicide tries in the month before the study clustered among those reporting severe suicidal thoughts with few fluctuations. No such association appeared in the hospitalized group, probably because most of those with each profile had been admitted shortly after suicide attempts. Following these people for a longer period, after hospital discharge, might yield a link between a specific profile of suicidal thinking and previous or new suicide attempts.

Kleiman is now participating in a similar study, directed by Harvard psychologist Matthew Nock, of 300 adults and 300 adolescents with histories of suicide attempts who will be monitored for six months after discharge from psychiatric facilities. Participants will respond to smartphone questions and wear sensors that monitor sleep and activity cycles. “Some people have difficulty recognizing how distressed they are in the moment, so we need to capture distress with nonverbal measures,” Kleiman says. By identifying these individuals, clinicians could help them to recognize physical signs of distress in themselves and devise a plan to get help when such signs occur, Klonsky adds.

A related proposal holds that at least two forms of suicidal thinking, one related to spikes in distress, exist and demand closer study in smartphone studies. Psychiatrist Maria Oquendo of the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine and colleagues suspect that the first consists of sudden bursts of suicidal thoughts following stressful experiences, possibly rooted in stress sensitivity due to child abuse or other early traumas. The second is linked to a consistently depressed mood that likely leads to carefully planned suicide attempts. Oquendo and her colleagues have found evidence for these two types of suicidal thinking in surveys of more than 6,700 U.S. college students.

Stress, or the lack of it, might play a role in some or all of the patterns of suicidal thinking identified by Kleiman’s group. Sleep and activity data in the team’s upcoming study may provide an indirect look at how stress affects suicidal thoughts.

Another digital-monitoring study in the works is that of psychologist Catherine Glenn of the University of Rochester in New York. She is currently assembling a smartphone-and-sensor study that will track 50 teenagers hospitalized following suicide attempts for one month after discharge. “It’s still unclear how much suicidal thoughts fluctuate over short periods of time, especially in youth,” Glenn says.

Despite its promise, digital monitoring of people at risk for suicide only works if people respond to repeated surveys. Consider that U.S. Army soldiers who refused to answer a survey question about the duration of their suicidal thoughts were especially likely to try later to kill themselves. A team led by Harvard psychologist Matthew Nock reported that finding in the February Journal of Abnormal Psychology. Rochester’s Glenn adds that some teens recently released from psychiatric facilities go offline for a couple of days before being hospitalized again for a suicide attempt.

“Suicide is such a complicated area of study,” Glenn says.

Editor’s note: This story was updated June 18, 2018, to clarify Evan Kleiman’s role in an ongoing study.