Readers weigh in on human gene editing and more

Your letters and comments on the January 20, 2018 issue of Science News

- More than 2 years ago

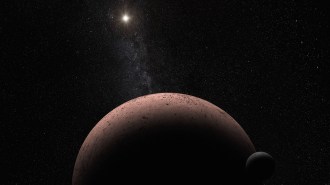

Mission: Mars

Mission: Mars

The possibility that human visitors could carry Earth-based microbes to the Red Planet has roiled the Mars research community, Lisa Grossman reported in “How to keep humans from ruining the search for life on Mars” (SN: 1/20/18, p. 22).

Reader Bruce Merchant speculated that Mars would need a protective global magnetic field to sustain a life-friendly environment. But the planet’s core cannot generate such a field, he wrote. Merchant suggested that the presence or absence of magnetic fields might be one way to tell whether a planet could support life. “Can we determine that for exoplanets?” he asked.

It’s unclear if a planet needs a core that produces a magnetic field to support any kind of life, Grossman says, “but that question is definitely something astrobiologists fret about.” We don’t have a way to determine from afar if an exoplanet has a core that would generate magnetic fields, she says. “But finding life on a planet with no magnetic field would be one way to test how necessary such fields are.”

Moral dilemma

If CRISPR and other gene-editing tools are approved for use in human embryos, some parents may feel morally obligated to use such a tool to give their children the best life possible, Tina Hesman Saey reported in “Parents may one day be morally obligated to edit their baby’s genes” (SN: 1/20/18, p. 4).

Several readers weighed in with their views on human gene editing.

Karla Garcia thought that using genetic editing to eliminate disease and improve life expectancy would be OK. But the technology shouldn’t be used for “human enhancement,” she wrote. “The fear of a class of genetically enhanced people is reason enough not to mess with the DNA.”

Readers on Twitter had similar sentiments. “It could go down the route of eugenics,” Annabel Ladomery wrote. Ashley Anand pointed out that a moral obligation is not the same as a legal requirement. But Andrew Patterson wondered if parents who choose to genetically alter their children could be held legally responsible for any unforeseen problems. “What if the child later objects to having been ‘designed?’ ” he asked.

The moral obligation, Tony Cusano wrote on Facebook, “will be to stay out of the way” until scientists better understand the complexity of human biology.

Keen eye

An AI program discovered that the star system Kepler 90 has an eighth world that had been overlooked in exoplanet searches, Maria Temming reported in “AI has found an 8-planet system like ours in Kepler data” (SN: 1/20/18, p. 12). Kepler 90 is now tied with our solar system for the known planetary family with the most members.

Online reader Jim Reed wondered about the likelihood of the Kepler space telescope spotting another solar system like ours.

Kepler wouldn’t detect an entire solar system identical to ours, but the telescope could find individual planets passing in front of their host star.

If Kepler looked at our solar system from a thousand light-years away, the telescope could probably detect only Venus or Earth, says Jeff Coughlin, an astronomer at the SETI Institute in Mountain View, Calif., and NASA’s Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, Calif. Mercury and Mars wouldn’t block enough sunlight for Kepler to spot them. And the outer giant planets take so long to orbit the sun that the telescope wouldn’t have stared long enough in its lifetime to catch one transiting, Coughlin says.

Corrections

In “Electric eels provide a zap of inspiration for a new kind of power source” (SN: 1/20/18, p. 13), voltage was incorrectly described as a measure of energy. Voltage is a measure of the difference in electric potential between two points.

Due to an editing error, “50 years ago, IUDs were deemed safe and effective” (SN: 2/3/18, p. 4), incorrectly stated that intrauterine devices block contraception. IUDs block conception.