A science-themed escape room gives the brain a workout

A quantum physicist discusses what he learned from starting LabEscape

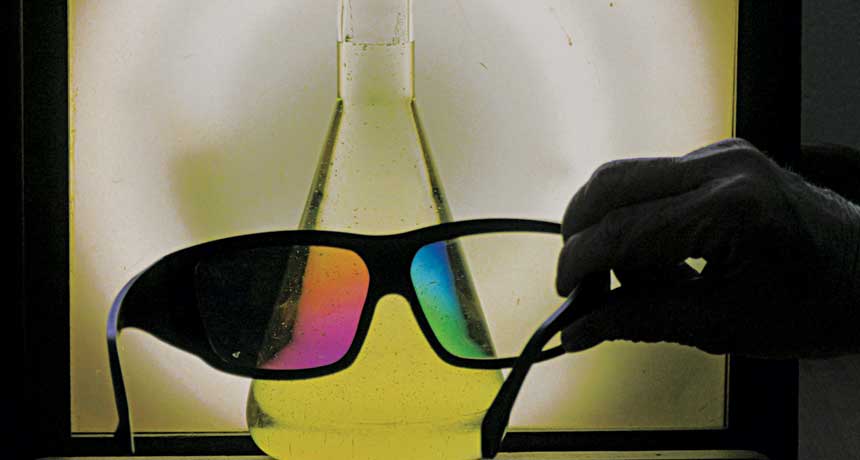

SWEET SURPRISE To unlock hidden messages in LabEscape, players must discover tricks of light. In this example, sugar molecules in the flask rotate light’s polarization, or the orientation of its electromagnetic waves, revealing colors that are visible through polarized glasses.

P. Kwiat/LabEscape