This scientist watches meat rot to decipher the Neandertal diet

Nitrogen-15 levels in putrefying meat could explain high levels of the isotope in hominid fossils

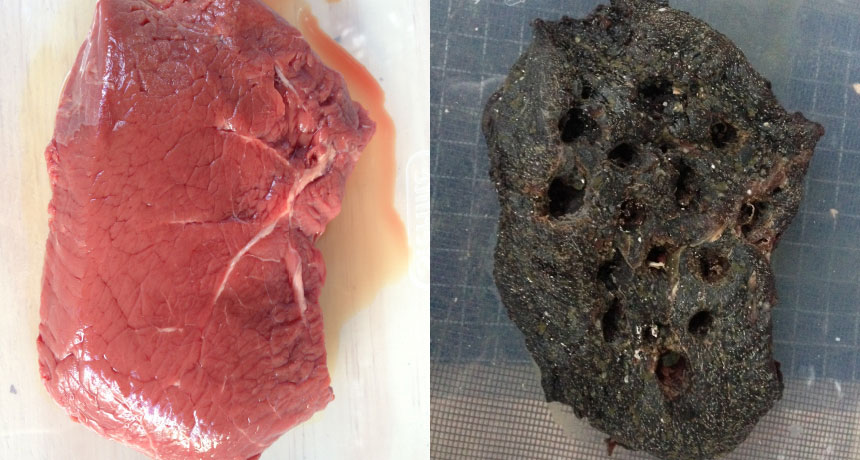

HIGH STEAKS Kimberly Foecke is measuring the biochemical changes of rotting meat, hoping to get a better understanding of Neandertal diets in the process. A fresh steak (left) has turned putrid and black by day 15 (right).

Kimberly Foecke