Breast screening tool finds many missed cancers

It causes less discomfort than a mammogram and costs less than an MRI.

A relatively new imaging option outperforms all comers in scouting for hidden breast tumors. Indeed, argues radiologist Rachel Brem, her team’s new data indicate that that “almost 10 percent of women with breast cancer have another [tumor] that we wouldn’t know about without this technology.”

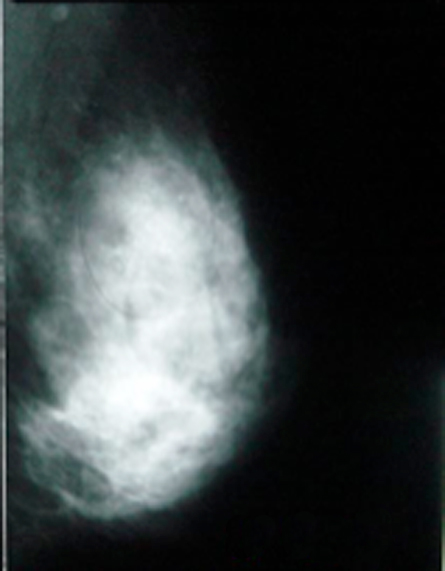

For all of its advantages, mammography misses some tumors and points out what appear to be cancers — but aren’t. That’s why physicians follow up suspicious mammograms using some adjunct technology. Usually magnetic resonance imaging, aka MRI scans. However, in recent years, a new technology — breast-specific gamma imaging, or BSGI — has been spreading in hospitals across the United States.

Doctors inject patients with a drug (methoxyisobutylisonitrile) that’s been tagged with the radioactive tracer technetium-99m, also known as Tc-99m. It’s the same combo used in cardiac stress tests and scans for parathyroid tumors. Known as Tc-99m sestamibi, this combo concentrates in breast tumors and emits gamma radiation that shows up on the equivalent of an x-ray.

It takes about 40 minutes for the BSGI scan, but women can sit in a chair and read or watch TV while it’s underway. And unlike mammograms, which can pinch breasts painfully, no one complains about discomfort from the nuclear-imaging procedure, Brem says.

BSGI has advantages over MRIs, not the least being cost and convenience for both hospitals and patients, Brem notes. It also can be used in many patients who can’t get an MRI, such as because they have heart pacemakers or other implants, are severely claustrophobic or are too big to fit inside the MRI magnet.

At George Washington University Medical Center in Washington, D.C., Brem’s team has been investigating whether BSGI is also as good as MRIs in giving physicians an expert second opinion on whether their patient has a tumor. In the June Academic Radiology, she and her colleagues now report that BSGI catches as many tumors as MRI — and offers fewer false positive readings (identification of apparent cancers that aren’t).

BSGI identified tumors among all 159 women who, owing to mammograms or breast self-exams, had a suspected cancer. In addition to the lumps that initially triggered this “second look,” BSGI also identified 56 additional apparent cancers. Although most of these proved benign, BSGI did pick up 23 true cancers that had been “occult” — not visible on mammography or self exams, often owing to their extremely small size.

Some bloggers have suggested BSGI could and should replace mammograms. Brem disagrees. The nuclear-imaging procedure costs more than mammograms, requires that patients be injected with a radioactive material and takes considerably longer to perform. That’s why she advocates its use only to confirm suspected tumors or scout for recurrent malignancy in women who had an earlier breast cancer.

More than most malignancies, breast cancer can be especially disfiguring — and in ways that a shirt may not hide. That’s why many women opt for taking out the cancerous lumps and leaving the rest of the breast intact. But this option is sound only when there’s a single tumor and it’s self-contained. Eagle-eye BSGI appears best suited to identifying which patients make good candidates for breast-conserving surgery, Brem says.

Currently, she notes, there are about 100 BSGI cameras in the United States and about four times that many elsewhere. Of course, there is the issue of the Tc-99m nuclear-contrast agent. For the past two years, it’s been in short supply owing to an international shortage in production of its parent isotope, the most widely used radioactive isotope used in diagnostic medicine.