‘Great Adaptations’ unravels mysteries of amazing animal abilities

Tales of unusual animals — and unusual science — make for an entertaining read

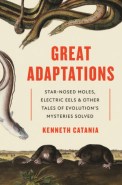

The pointy snout of the star-nosed mole helps the animal sense its environment while underground, as Kenneth Catania explains in Great Adaptations.

blickwinkel/Alamy Stock Photo

Great Adaptations

Kenneth Catania

Princeton Univ., $27.95

Neurobiologist Kenneth Catania’s passion for scrutinizing odd animal adaptations all started with a creature with a 22-point star on its face.

Catania first saw a star-nosed mole (Condylura cristata) in a children’s book. Later as a 10-year-old, he found a dead one near a stream close to his home in Columbia, Md. From then on, he kept his eyes peeled for more. He had to wait until he was in college, when he landed a research position that required him to trap star-nosed moles in Pennsylvania’s wetlands. At the time, no one knew what that unique nose was good for, and he wanted to figure it out.

In Great Adaptations, Catania describes his pursuit of the mystery behind the mole’s wiggly star-shaped appendage (it helps the subterranean animal sense prey without using sight) as well as a slew of other animal tricks. The account of his adventures as a biological sleuth provides a detailed look at curiosities such as how “hangry” water shrews execute the fastest documented predatory attack by a mammal and how cockroaches resist becoming zombies during parasitoid wasp attacks (SN: 10/31/18).

“It’s part of human nature to be intrigued by mysteries, but the mystery only gets us to the door,” he writes. “You never know what you might find on the other side.”

In search of answers, Catania has set up some odd, but amusing, experiments. To film wasps attacking cockroaches, he built a set fit for a horror flick, by filling a tiny kitchen with warning signs and a plastic human skull for the wasp to store its zombified victim in. Keeping with the horror theme, he also stripped the paint off decorative severed zombie arms and offered the plastic limbs to electric eels (Electrophorus electricus) to show that the animals leap out of the water as an attack strategy (SN: 6/9/16).

Sign up for our newsletter

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.

Each chapter follows a logical flow as Catania describes his discoveries, from what first piqued his interest in an animal to his ultimate findings. Science, however, is rarely as straightforward as he makes it seem. Catania’s scientific detective work didn’t always go off without a hitch, but, he notes, including all the failures would have meant a much longer book. Even so, the book alludes to some ideas that didn’t pan out. “The animals are always able to do something unexpected and more interesting than I’d imagined,” he writes.

For instance, the notion that a tentacled snake (Erpeton tentaculatum) might use the short appendages close to its mouth to lure in nearby fish, just like snapping turtles do with their tongues, turned out to be wrong. Instead, the tentacles help a snake sense a fish’s position in the water and know when to attack. What’s more, the snakes have hacked their prey’s natural escape reflexes. In a fatal mistake, fish flee in the wrong direction — straight toward a snake’s mouth — when duped by a twitch of the snake’s neck right before the predator strikes.

Catania’s lighthearted yet informative narrative presents science in a way that’s easy for anyone with a basic knowledge of biology to understand. But even the most seasoned expert will likely learn new details, the type that never make it into a scientific paper. For a particularly daring experiment, in which Catania offered his own arm for an electric eel’s shock to measure the shock’s electricity, Catania admits that he certainly couldn’t subject another animal or a student volunteer to the unpleasant jolt (SN: 9/14/17). His own arm was the “obvious solution.”

In page after page, Catania’s enthusiasm and awe for the animals shine through. When he discovered tentacled snakes are born knowing how to strike at prey rather than learning through failure, Catania recalls that he couldn’t “find enough superlatives to sum up these results.” He also describes a fight between a parasitoid wasp and a cockroach as an “insect rodeo.” The wasp attacks a cockroach’s head in an attempt to lay an egg, but in defense the roach “bucks, jumps, and flails with all its might.”

Some of that enthusiasm will likely rub off on readers and spark a sense of wonder. Great Adaptations packs in plenty of astounding details about some remarkable creatures. As Catania puts it: “I’ve stopped assuming I know the limits of animal abilities.”

Buy Great Adaptations from Amazon.com. Science News is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program. Please see our FAQ for more details.