Childhood bullying leads to long-term mental health problems

Being picked on by peers worse threat than child abuse, study suggests

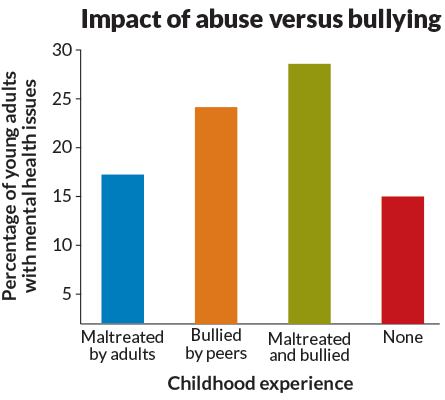

WITHOUT PEER U.S. and British evidence indicates that repeated bullying in childhood leads to at least as many or more mental health problems in young adulthood as maltreatment by adults does.

O Driscoll Imaging/Shutterstock

Bullying by peers scars children’s mental health over the long haul as much as — or more than — abuse by adults does, a new analysis of U.S. and British kids finds.

By young adulthood, many victims of repeated bullying experience anxiety, depression, self-harm and suicidal thinking and behavior. Their rates of these mental health issues are at least as high as those reported by victims of both child abuse and bullying, say psychologist Dieter Wolke of the University of Warwick in Coventry, England, and his colleagues.

Being maltreated by adults — but not picked on by peers — generally leads to fewer long-lasting mental health issues. Abused-but-not-bullied British children display rates of mental problems as young adults comparable to those of kids who were neither maltreated nor bullied, Wolke’s team reports online April 28 in Lancet Psychiatry. Abused U.S. children have a greater risk of later depression (but no other mental health problems) compared with kids who were not maltreated or bullied.

“Bullying is not a harmless rite of passage or an inevitable part of growing up,” Wolke says. “It has serious, long-lasting, detrimental effects on children’s lives.” About one in three children worldwide report having been bullied, he says.

Until now, researchers haven’t compared the long-term psychological effects of child maltreatment and bullying, Wolke says.

The new findings underscore the need for parents, schools, child protection services and other agencies to coordinate antibullying efforts, says Corinna Jenkins Tucker, associate professor of family studies at the University of New Hampshire in Durham. But the key question is not whether it’s worse to be bullied at school or battered at home, she holds. Children can get victimized in many ways and situations, making simple comparisons misleading, in her view.

In a comment published in the same Lancet Psychiatry, Tucker and University of New Hampshire sociologist David Finkelhor advise researchers to study how various forms of victimization add up over time to influence mental health. Cumulative effects of maltreatment by adults, exposure to family violence, having personal property stolen, bullying by a sibling, online bullying and dating violence — to name a few — have yet to be investigated, they say.

Wolke’s findings come from England’s Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children and the Great Smoky Mountains Study in North Carolina. In the British study, mothers of 3,904 children provided information on abuse and neglect at home from ages 8 weeks to 8.6 years. Children’s reports of being bullied were obtained at ages 8, 10 and 13. Mental health interviews were conducted at age 18.

In the U.S. study, 1,273 children annually reported past incidents of parental abuse and bullying from ages 9 to 16. A parent of each child also provided maltreatment and bullying information each year. Final psychiatric assessments occurred as late as age 26.

Mental health problems affected 15 percent of British participants who had not been bullied or maltreated. That figure reached 17 percent in cases of maltreatment only, 24 percent when only bullying had occurred and 28 percent for those who had been maltreated and bullied.

In the U.S. sample, young adults who had only been bullied displayed the highest percentage of mental health problems — 36 percent, followed by those who had been maltreated and bullied at 30 percent.

Regardless of bullying, certain types of child abuse were especially harmful to mental health, Wolke says. In both studies, rates of mental health problems were elevated for those who had experienced sexual and emotional abuse, but not physical abuse or harsh parental discipline.

Editor’s note: This article was updated on May 8, 2015, to clarify information about the final assessment in the U.S. study.