College biology textbooks still portray a world of white scientists

Recent shifts to include more women and people of color still lag behind students’ diversity

College biology students are getting more diverse. That diversity isn’t mirrored in the textbooks they study from.

Wavebreakmedia/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Charles Darwin. Carolus Linnaeus. Gregor Mendel. They’re all men. They’re all white. And their names appear in every biology book included in a new analysis of college textbooks. According to the survey, mentions of white men still dominate biology textbooks despite growing recognition in other media of the scientific contributions of women and people of color.

The good news, the researchers say: Scientists in textbooks are getting more diverse. The bad news: If diversification continues at its current pace, it will take another 500 years for mentions of Black/African American scientists to accurately reflect the number of Black college biology students.

“Biology is still a very white discipline, so the results were not incredibly surprising,” says Cissy Ballen, an education researcher at Auburn University in Alabama. By identifying scientist names and determining when their research was published, Ballen and her colleagues looked at trends in seven of the most commonly used college biology textbooks. They published their results June 24 in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

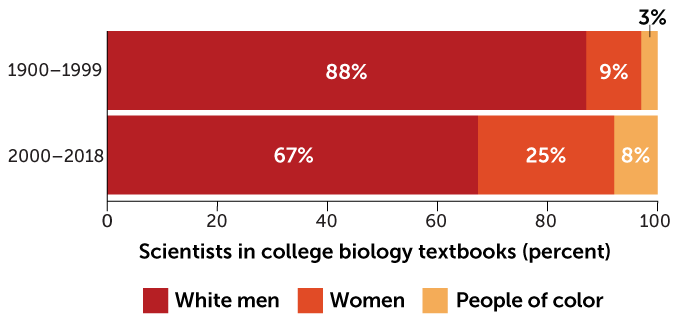

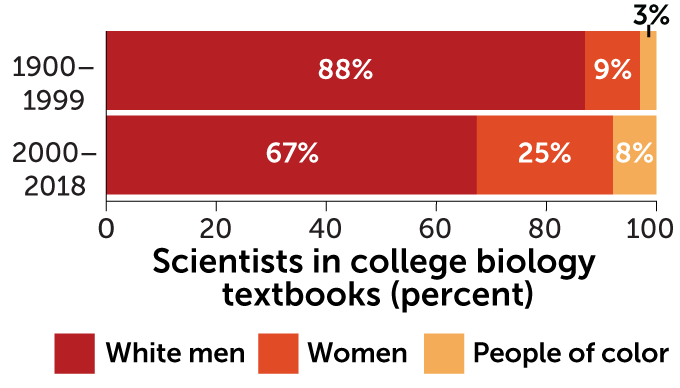

The team found that for research published between 1900 and 1999, only about 9 percent (or 55 out of 627) of scientists mentioned were women, and 3 percent (19) were people of color. But for research published between 2000 and 2018, women got 25 percent (87 out of 349) of the mentions, and people of color 8 percent (27). Some of this was representative; the number of women mentioned was proportional to the number of tenured women in the academic biology workforce over time, based on the National Science Foundation’s Science and Engineering Indicators. Information about the number of tenured people of color was not available.

But the numbers were not representative of the much more diverse biology student body. Based on the change seen from the 1900s to the 2000s, Ballen and her colleagues extrapolate that it will take decades — or even centuries — for textbook mentions of scientists to reflect the gender and racial diversity of who’s in the classroom. Speficically, it will take 28 years to catch up when it comes to highlighting women scientists, 50 years for Asian scientists, 30 years for Hispanic/Latinx scientists and 500 years for Black/African American scientists. Scientists in some groups — such as Black/African American women — were never mentioned in the books at all.

By the book

Auburn University education researcher Cissy Ballen and her colleagues ran an analysis by gender and race of scientists mentioned in seven major textbooks used in introductory college classes. Before 2000, 88 percent of scientists highlighted in textbooks were white men. Between 2000 and 2018 that number dropped to 67 percent, as textbook authors referenced more women and people of color.

Change in race and gender of scientists in college biology textbooks, 1900s vs. 2000s

The issue of who’s highlighted is only one aspect of the diversity problem, says Mark Lee, a biochemist at Spelman College in Atlanta, Ga. Textbooks are also written from a very white perspective, he notes. As an example, take a perm. Yes, the hair treatment. It comes up in biochemistry textbooks, Lee explains. “The chemistry part is just resetting disulfide bonds.” But textbooks define a perm as making straight hair curly. In fact, the same process can make naturally curly hair straight. Teaching at the all-women, 97 percent African-American Spelman, Lee says, that’s not a matter of semantics. “It’s about lived experience, and about how your lived experience is different from mine.”

When it comes to increasing diverse perspectives in science, Lee says, “I don’t think textbooks are the solution.” But they can certainly be better. “Publishers could make sure they have representation that is diverse on the writing team,” he notes.

One driving factor is that most biology textbooks are presented as a history of science, Ballen says. No women from the 1600s through 1900 were mentioned in the books surveyed. “That’s 300 years of just white men in textbooks,” she says. Instead, biology textbooks could be written with more emphasis on illustrating concepts with contemporary examples, instead of historical ones. “When you look at contemporary examples, you get more diversity; both women and scientists of color have greater access to biology, they are more accessible for textbook authors and publishers to find, and more prominent in their field.”

Trustworthy journalism comes at a price.

Scientists and journalists share a core belief in questioning, observing and verifying to reach the truth. Science News reports on crucial research and discovery across science disciplines. We need your financial support to make it happen – every contribution makes a difference.

Because scientist is based on historical findings, though, some history is necessary. “Textbooks have to be a blend of historical and modern,” says Peter Minorsky, a plant physiologist at Mercy College in Dobbs Ferry, N.Y. “If it’s all historical, then it’s not up to date. If it’s all cutting-edge, there’s no context.” Minorsky is one of the authors of Campbell Biology, a textbook included in the survey, and notes that the authors are making substantial efforts to include diverse scientists. There is a note at the end of the first chapter noting how under-representation of diverse views hampers the progress of science. And each section is accompanied by an interview with a modern scientist — none of whom are white men.

Lee certainly isn’t waiting for a more diverse textbook. Instead, he emphasizes examples from his own published science and the research being done at Spelman. “Professors have to be versed in the conventional presentation and then bring in extra content,” he says. Then, students will “see science being done by individuals like them,” instead of feeling that they are making isolated forays into the field.

Mentoring is also crucial. “Diversity isn’t ethnicity and numbers of people; it’s about your attitude,” he says. “We can’t wait until the industry is diverse. I’m asking [professors] to take on the burden of being diverse by supporting a diverse population.”