Why COVID-19 is both startlingly unique and painfully familiar

The coronavirus has a lot of tricks up its sleeve, but not all of them are new

On April 25, Janice Brown was released from a Victorville, Calif., hospital after recovering from COVID-19. It was her second hospitalization due to the illness, which can grip some patients for weeks on end.

Irfan Khan/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

For Abby Knowles, a headache and fatigue was just the start.

She soon felt like she had a tight band across her chest, making it difficult to breathe. She developed pain in her upper body, which led doctors to check if she was having a heart attack (she wasn’t). Her blood pressure began to oscillate — too low, too high — leaving her lightheaded and nauseous. Her mind became so foggy she couldn’t read a book.

A symptom might taper off, only to return. “You’ll think, ‘Oh I’m done with that bit, brilliant,’” Knowles says, “and then three days later it will be back.” After more than three months of illness, Knowles — who is 38 and lives in Reading, England — has been referred for an evaluation for long-term complications from COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus SARS-CoV-2. Meanwhile, her husband Dan, who also became sick toward the end of March, had a high fever and more typical COVID-19 symptoms for a few days but soon recovered.

The experiences of the Knowles and many COVID-19 patients point to the ways that the coronavirus can be maddeningly unpredictable. Some people have debilitating illness, while others barely feel sick, if at all. For some, it’s mostly a respiratory illness, while others have neurological symptoms (SN: 6/12/20), such as loss of smell (SN: 5/11/20). Severely ill patients may develop life-threatening blood clots (SN: 6/23/20), adding vascular symptoms to the list. Some patients are struggling to get back to normal long after being sick.

COVID-19:

The first six months

This story is one in a series looking at the first six months of the pandemic.

And the way the disease plays out by age can be baffling. Severe cases of COVID-19 have been rare among children, but some have suffered a dangerous inflammatory syndrome that can appear weeks after an infection (SN: 6/3/20). Older people remain at highest risk for hospitalizations and death from COVID-19, but young adults are getting seriously ill, too (SN: 3/19/20). That group generally tends to fare better than the very young and very old with viral infections (one glaring exception: the 1918 flu pandemic, which killed healthy, young adults at a high rate).

In the six months since China reported a pneumonia of unknown cause, doctors have described a burgeoning catalog of health harms from what’s now called COVID-19. In some ways, the disease stands apart: The range of COVID-19’s effects and the difficulty in predicting how severely it will hit any one person is out of the ordinary. But some of the symptoms and patterns associated with COVID-19 are painfully familiar.

Combating COVID-19 — there are now over 10.5 million confirmed cases worldwide, and more than half a million have died of the disease — will take a better understanding of how it operates at every level, from the microscopic on up. Moving from the viewpoint of a cell to a person to society, here’s a look at how COVID-19 compares to other viral infections and the harms they inflict.

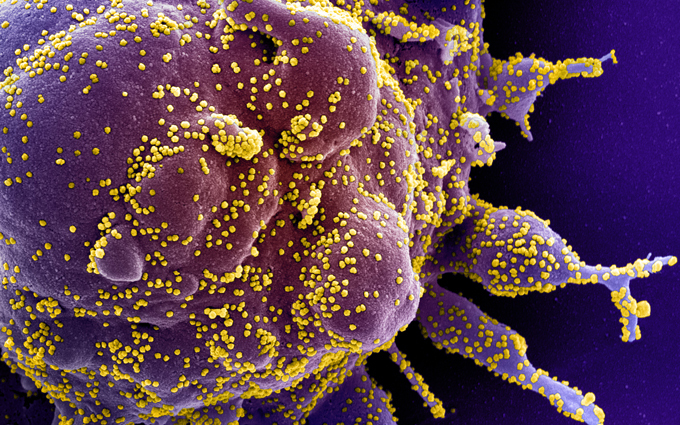

Peering at the cell

Studying how SARS-CoV-2 interacts with the immune system has revealed some surprises along with one explanation for why COVID-19 can be a severe illness.

During a viral infection, the infected cells put out a call to arms and a call for reinforcements, says virologist Benjamin tenOever of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. The cells release interferons, proteins that “signal to all of the neighboring cells that there’s a virus present,” he says. The cells also send out proteins called chemokines, which attract immune cells to the site of infection.

Viruses endeavor to overcome both calls. Influenza, for example, dampens each enough to replicate and move to another host, but not so much that a person can’t eventually clear the infection. SARS-CoV-2 does something different: It slams the brakes on the call to arms but puts the gas on the call for reinforcements, tenOever says.

In experiments with cells, animals and blood and tissue samples from COVID-19 patients, tenOever and his colleagues found low levels of interferons, which sound the call to arms. But levels of chemokines, which bring in the cavalry of immune cells, were high, the researchers report May 28 in Cell.

“It makes no sense,” tenOever says, as the juiced up call for reinforcements “doesn’t even necessarily benefit the virus.” But it can cause big problems for patients. The excessive show of immune cell force spurs inflammation and cell death, which can stoke yet more inflammation and cell death. This severe immune reaction can damage the lungs and other organs.

The way that SARS-CoV-2 tangles with the immune system largely sets it apart from other viruses, although SARS-CoV — the coronavirus behind the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome outbreak in 2003 — also showed the same mismatched approach to the call to arms and call for reinforcements, tenOever says. And the Ebola virus does something a little similar, although for a different reason, he says. That virus is good at blocking the call to arms, but it damages so many cells quickly during an infection that it ends up triggering a lot of inflammation, even though it isn’t revving up the call for reinforcements.

From person to person

Many of the symptoms and complications associated with COVID-19 are seen with other viral infections. For example, loss of smell, called anosmia, can occur during infections with common cold-causing coronaviruses and other viruses that target the upper respiratory tract. Fatigue is common with such viral illnesses as mononucleosis, which is usually caused by the Epstein-Barr virus. Blood clotting problems can occur in patients severely ill with certain viral infections.

But the sheer breadth of symptoms and complications associated with this illness is unusual. With COVID-19, “we are seeing such a devastatingly wide range of effects,” says infectious disease physician Anna Person of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville.

Person knows COVID-19 both as a doctor and a patient. The Sunday in late April that the avid runner became ill started like any other and included a seven-mile run. But that evening, “I just had a wave of feeling horrible,” Person says, with chills and signs of a fever. “It hit me like a sledgehammer.”

During Person’s bout of COVID-19, she temporarily couldn’t smell or taste — coffee tasted like water, she says — and she experienced confusion and memory problems. Two months on, she’s slowly starting to feel like herself, but it’s taken longer than she expected. She has begun running again, but still battles heavy fatigue. Yet her case is considered mild because she didn’t need to be hospitalized.

The risk of severe illness and death from COVID-19 increases with age and with certain underlying conditions, but younger, healthy people are also ending up on ventilators or having strokes. What’s so unpredictable, Person says, is that “while we have studies that have told us certain risk factors for more severe disease, we’re seeing so many exceptions to that.”

Severe illness is no stranger to other viral infections, from dengue to West Nile to measles to chickenpox and shingles (SN: 2/26/19). And with respiratory viruses such as the flu, “there’s always a subset of people who present with very severe infection,” says infectious disease specialist Preeti Malani of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Those patients can end up with acute respiratory distress syndrome, or ARDS, a deadly condition that deprives the organs of oxygen. But with COVID-19, she says, “clearly it’s a very different scale.”

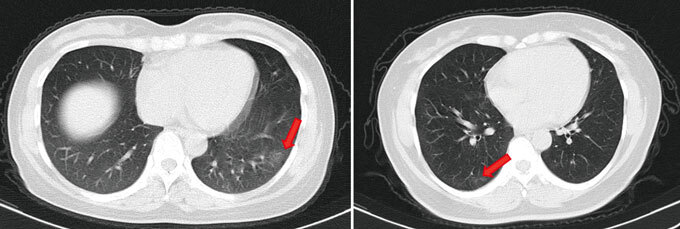

Even those who seem to pass through a SARS-CoV-2 infection without a sniffle may not come out unscathed. Researchers assessed 37 people who tested positive for the coronavirus but didn’t have symptoms in the two weeks before their test or during their isolation in the Wanzhou People’s Hospital in China. Twenty-one had abnormal features in their lungs that have been seen in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, the researchers report online June 18 in Nature Medicine.

That leaves open the possibility that asymptomatic people, not just those with symptoms, may end up with long-term consequences. “One of the concerns is, are these people going to be left with lungs that don’t function normally?” Malani says.

Social scenarios

There is still much to learn about why an individual person might be more or less at risk of developing complications or long-term damage from COVID-19. But there’s little question anymore that certain scenarios put a person at higher risk of getting an infection in the first place. The virus mainly spreads by respiratory droplets, generated by coughing, sneezing or talking, when people are in close contact (SN: 6/18/20).

“Who are the people who are more likely to be in constant close contact with others, who are not able to isolate from respiratory droplets, who are not able to work from home?” says Jasmine Marcelin, an infectious disease physician at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha. Those “often times are minority communities.”

The racial and ethnic disparities in terms of who has access to health care, owns a home and has a job that can be done remotely have produced stark differences in who gets sick and dies from COVID-19 (SN: 4/10/20). An analysis at the U.S. county level shows that greater social vulnerability — a measure which takes into account socioeconomic status, minority status, access to housing and transportation and other factors — is associated with a higher risk of being diagnosed with COVID-19 and a higher risk of death from the illness, researchers report online June 23 in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

Most patients hospitalized at Vanderbilt University Medical Center with COVID-19 are from communities of color, says Person. “It’s systemic racism at work.”

This isn’t the first pandemic to disproportionately burden Black, Latino and Native American communities. For example, the H1N1 flu pandemic in 2009 was riskier for these Americans. And there is evidence that, even though fewer were infected, Black Americans were more likely to die from the 1918 pandemic flu than white Americans, researchers report online June 5 in Annals of Internal Medicine. “These problems have existed for centuries,” says Marcelin. Inequities “permeate every aspect of society, including health care and the way we respond to health care crises.”

All told, COVID-19 leaves us both with déjà vu and the sense we’re blazing new territory. Certainly some of what’s so transformative about the experience is that many of us are living through a pandemic of this scale for the first time, as we face a virus our bodies have never seen before. Because the coronavirus is new, “we’re learning on the job,” Marcelin says. “That makes it a lot more scary to think about.”

Trustworthy journalism comes at a price.

Scientists and journalists share a core belief in questioning, observing and verifying to reach the truth. Science News reports on crucial research and discovery across science disciplines. We need your financial support to make it happen – every contribution makes a difference.