Drugs Counter Mad Cow Agent in Cells

Fueled only by promising studies of cells, a California research team has invited controversy by beginning to give a little-used malaria drug to patients who have the human version of mad cow disease.

The drug, quinacrine, is one of two that the investigators report clear brain cells of abnormally shaped proteins called prions. These are the infectious agents responsible for the neurodegenerative illness, which is called Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). The second drug is chlorpromazine, commonly prescribed for schizophrenia and other mental illnesses.

The researchers include Stanley B. Prusiner, who won a Nobel prize for his pioneering work on prions (SN: 10/11/97, p. 229). They describe their new studies of cells in the Aug. 14 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). This week, the team also announced plans to quickly launch a trial of the drugs in people dying from CJD.

In fact, the scientists reveal that they are already using quinacrine to treat two patients. One continues to decline. The other, a 20-year-old Englishwoman, has improved and shed her wheelchair, according to accounts in London tabloids.

Science News has learned, however, that quinacrine hasn’t shown effectiveness in mice with a prion-based disease similar to CJD. Last year, Katsumi Doh-Ura of Kyushu University in Fukuoka, Japan, and his colleagues began testing the drug on animals after also finding that quinacrine, as well as related antimalarial drugs, inhibit prion buildup in infected cells.

They reported their cell studies in the May 2000 Journal of Virology and are preparing a paper on the new animal studies. A human trial of quinacrine “seems to be premature,” says Doh-Ura.

A leading prion scientist concurs.

“Although I agree with moving rapidly to human trials with compounds with proven preclinical efficacy, I am worried [that] a proliferation of many not-well-controlled trials of drugs not properly studied will lead to unclear results,” says Claudio A. Soto of the Serono Pharmaceutical Research Institute in Geneva, Switzerland.

It’s a tough choice, notes another prion expert. “From a scientific standpoint, going from a cell-culture system, which is very artificial, to humans is not done. On the other hand, you’re talking about drugs that have been widely used in humans . . . and it’s an invariably fatal disease,” says

Richard T. Johnson of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

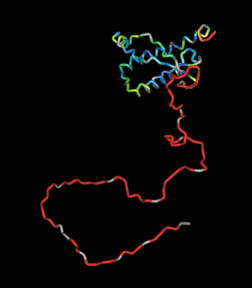

Brains infected with prions become riddled with holes when the proteins convert their normal counterparts into more prions. Traditional CJD strikes only 1 person in a million. However, a new form, which arises in people who have eaten beef from cattle with mad cow disease, has killed about 100 people over the past decade. The unconfirmed fear that such beef has infected thousands of people has created near-hysteria in much of Europe.

The prion-fighting capability of chlorpromazine or quinacrine emerged when Carsten Korth of the University of California, San Francisco tested a wide range of compounds that can pass from the body into the brain, a feat that few drugs can perform. When Korth, Prusiner, and their colleagues applied the drugs to infected mouse brain cells in lab dishes, prions gradually disappeared.

Why remains unclear. “We have no idea how these drugs work,” says Korth, noting that even after treatment stopped, prions didn’t reappear.

According to the cell studies, quinacrine is the more potent of the two drugs. But Korth speculates that chlorpromazine may be more effective in people since its normal site of action is the brain.

Two other new studies suggest that antibodies that prevent prions from converting normal proteins to deadly forms can also clear infected cells of prions. In the Aug. 16 Nature, R. Anthony Williamson of the Scripps Research

Institute in La Jolla, Calif., describes several such antibodies. A group headed by Charles Weissmann of the Medical Research Council Prion Unit in London reports a single prion-clearing antibody in the July 31 PNAS.

In cell studies, says Williamson, antibodies are even more potent than quinacrine and chlorpromazine at clearing prions. Antibodies, however, are relatively large molecules and therefore have difficulty crossing into the brain from the blood, he notes.