Gastric bypass controls diabetes long term better than other methods

Bariatric surgery checks the disease more so than other weight-loss measures

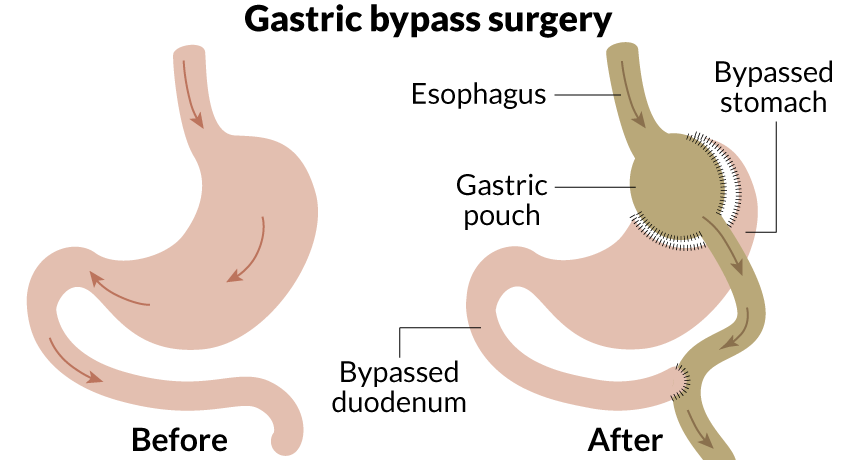

STOMACH SURGERY Gastric bypass surgery reduces the size of the stomach and shortens the digestive path for food. While performed for weight loss, the procedure may also bring long-term remission of diabetes.

E. Otwell

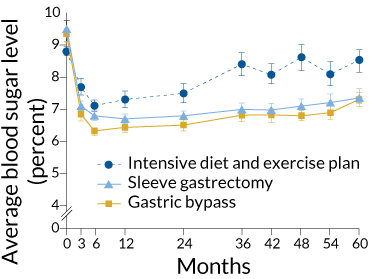

People who undergo gastric bypass surgery are more likely to experience a remission of their diabetes than patients who receive a gastric sleeve or intensive management of diet and exercise, according to a new study. Bypass surgery had already shown better results for diabetes than other weight-loss methods in the short term, but the new research followed patients for five years.

“We knew that surgery had a powerful effect on diabetes,” says Philip Schauer of the Bariatric & Metabolic Institute at the Cleveland Clinic. “What this study says is that the effect of surgery is durable.” The results were published online February 15 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study followed 134 people with type 2 diabetes for five years in a head-to-head comparison of weight-loss methods. At the end of that time, two of 38 patients who only followed intensive diet and exercise plans were no longer in need of insulin to manage blood sugar levels. For comparison, 11 of 47 patients who had a gastric sleeve, which reduces the size of the stomach, and 14 of 49 who underwent gastric bypass, a procedure that both makes the stomach smaller and shortens digestion time, did not need the insulin anymore. In general, patients who had been diabetic for fewer than eight years were more likely to be cured, Schauer says.

Even those surgical patients who still needed to take insulin had greater weight loss and lower median glucose levels than others in the study. This study was also one of the few to show that bariatric surgery could help those with only mild obesity, defined as a body mass index between 27 and 34. How bariatric surgery might improve diabetes is still unknown, but scientists have pointed to effects on the body’s metabolism (SN: 8/24/13, p. 14) and gut microbes (SN: 9/5/15, p. 16).

The same research team had published similar results at one and three years after surgery, but few studies looked further, says Kristoffel Dumon, a bariatric surgeon with the University of Pennsylvania Health System in Philadelphia. “The criticism of bariatric research has been that there are no good long-term results. With weight-loss surgery, you often see rapid initial results, but you want to see that to a five-year time point.”

Dumon also notes that the patients who received only intensive medical therapy did not report an improvement in their quality of life, and their emotional well-being worsened. People in the surgical group reported improvements in quality of life, but not in emotional well-being, a finding that Schauer says has more to do with stress management and other characteristics that wouldn’t necessarily be affected by surgery.

Schauer hopes to have even longer-term data in the future. His team will combine their results with those from similar research at three other U.S. sites with the goal of following patients for up to 10 years.