Tiny worms can live in solid rock up to 3.6 kilometers underground, researchers have found, far deeper than anyone has encountered complex organisms before. The discovery of nematode worms in three South African gold mines underscores that Earth’s biosphere reaches well into subterranean realms. It also suggests habitable environments may exist buried way down on other planets, such as Mars.

Worm specialist Gaetan Borgonie and his colleagues present their findings, which include a new nematode species named after Faust’s devil Mephistopheles, in the June 2 Nature. Nematodes are an incredibly diverse group encompassing numerous intestinal parasites and the widely studied laboratory roundworm C. elegans.

Over the past few decades, researchers have found plenty of bacteria and other single-celled creatures thriving deep underground. But “to actually go out and start looking for multicellular organisms is such a game changer. Nobody in their right mind would think they were down there,” says team member Tullis Onstott, a geomicrobiologist at Princeton University.

But Borgonie, of the University of Ghent in Belgium, thought there just might be enough food, water, oxygen and other nematode necessities to keep worms alive deep in Hades’ realm. So he traveled to South Africa to collect water and soil samples from six boreholes.

In the deepest, 3.6 kilometers down at the Tau Tona gold mine, Borgonie found traces of nematode DNA in water oozing from rock fractures. Much shallower, 900 meters down the Driefontein gold mine, he found actual nematodes of two known surface species. And in the middle depths, 1.3 kilometers down in the Beatrix gold mine, he uncovered an odd-looking female nematode.

Back in the laboratory, Borgonie laid the living worm under a microscope. “It was like an intensive care unit — I was looking at it every hour,” he says. “The only thing I wanted it to do was lay an egg.”

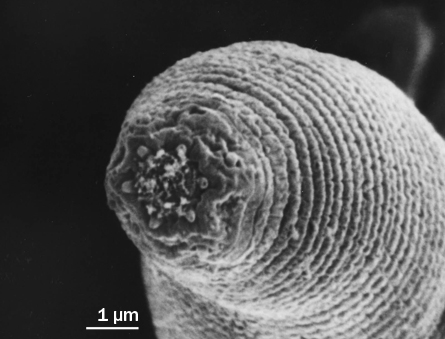

It did. Eight of them. Borgonie had the start of a worm dynasty. About half a millimeter long, the nematodes are different enough from other species to warrant their own name: Halicephalobus mephisto.

To make sure the worms weren’t accidentally brought down by mine workers, the researchers ran a painstaking series of tests. The studies showed that the water in which the nematodes live is at least several thousand years old.

Before that, Borgonie says, ancestors of the worms he found probably lived on the surface. Over generations they presumably slithered down, munching bacteria along the way. “If it can work its way through the fractures and keep on picking up goodies, it doesn’t really care about how deep it is,” says Onstott. “Given enough time, these organisms will get there.”

Nematodes can live with hardly any oxygen; the limiting factor to their survival in the deep is probably temperature, Borgonie says. In lab cultures H. mephisto survived up to 41° Celsius.

But R. John Parkes, a deep biosphere expert at Cardiff University in Wales, questions whether drilling boreholes for the mines altered the subsurface environment somehow, perhaps by introducing more oxygen or otherwise providing an artificial environment for nematodes to thrive.

In a few months Borgonie will return to South Africa to hunt for new nematodes in mine water he’s been collecting and filtering for two years — far longer than the 24-hour samples he reports on in the new study.

Karsten Pedersen, a microbiologist at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, says he’s convinced by the hard work the team did to rule out the possibility of surface contamination. Pedersen has found yeast up to 450 meters deep in Swedish granite, the previous record holder for complex subterranean life, but hasn’t yet looked for nematodes there. More research is needed, he says, to confirm whether the South African deep worms are a rarity or the rule.