Visitors to Yellowstone National Park’s geothermal springs are struck as much by the stench as by the landscape. The sulfur compounds emanating from the springs bear a rotten-egg odor, and they have long been regarded as a major source of energy for the springs’ rich community of microorganisms. New research, however, suggests this positive spin on sulfur may be overblown. Most microorganisms in the springs seem to live off hydrogen, scientists report.

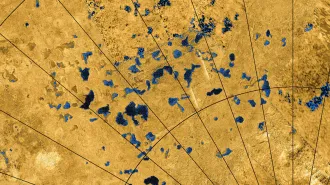

To find out what kinds of microbes inhabit these extreme environments, where water temperatures can surpass 70°C, researchers at the University of Colorado at Boulder collected bacteria-bearing sediment samples from Yellowstone’s geothermal system. Then, the team sequenced some of the microbes’ genes. Much to the researchers’ surprise, the sequences in most of the microbes closely resembled those of hydrogen-metabolizing bacteria that had been characterized elsewhere.

With extensive measurements, the researchers also determined that molecular hydrogen is abundant throughout the geothermal system. “These are the first systematic measurements of hydrogen in Yellowstone’s springs,” says lead investigator Norman Pace.

His computer model suggests why, even in the presence of sulfur, bacteria favor hydrogen. It’s because sulfur-metabolizing organisms require oxygen, which serves as the depot for electrons that the microbes strip from sulfur. At temperatures greater than 70° C, however, oxygen is poorly soluble. So, most of the microbes living in the geothermal springs turn to hydrogen instead.

Pace and his colleagues describe their results in an upcoming Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Although hydrogen-consuming bacteria have been found in other low-oxygen environments, such as rice paddies and cow rumens, the new study hints that such microbes may be surprisingly prevalent.

“This will popularize the importance of hydrogen metabolism in the environment. Most people don’t think about it very much,” says Pace. The finding also implies that many bacteria in deep-sea hydrothermal vents, for instance, may metabolize hydrogen instead of sulfur.

Although he finds the Colorado group’s findings surprising, Ken Nealson of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles says that they also make a lot of sense. “Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe,” he notes. “Any wise organism would choose hydrogen over sulfur.”

Nealson says that Pace’s results may not only cause researchers to take a closer look at the microbes on Earth but also stimulate new ideas for scientists searching for life on other planets. For instance, volcanic activity and other hydrogen-generating geochemical processes that have been observed in the solar system might host microbial life, says Nealson.