In the Middle Ages, the early Catholic Church banned marriage between even distant relatives. A resulting transformation in family structure partly explains why Westerners today are more individualistic, a study suggests. This illustration shows Henry V, the King of England in the early 1400s, marrying Catherine of France in 1420.

duncan1890/Getty Images Plus

During the Middle Ages, decrees from the early Catholic Church triggered a massive transformation in family structure. That shift explains, at least in part, why Western societies today tend to be more individualistic, nonconformist and trusting of strangers compared with other societies, a new study suggests.

The roots of that Western mind-set go back roughly 1,500 years when a branch of Christianity that later evolved into the Roman Catholic Church swept across Europe and beyond, report human evolutionary biologist Joseph Henrich and colleagues in the Nov. 8 Science.

Leaders of that branch became obsessed with what they saw as incest, the researchers say, and launched a “marriage and family program” that eventually banned marriages between even distant cousins, step-relatives and in-laws. Church policies also encouraged marriage by choice instead of arranged marriages, and small, nuclear households, with couples living separately from extended family members.

Using historical, anthropological and psychological data, Henrich and his colleagues show that the Church’s policies helped unravel the tight, cohesive kin networks that had existed. In places under the Church’s influence, a Western-style mind-set has come to dominate, the team says.

“Human psychology and human brains are shaped by the institutions that we experience and the most fundamental of human institutions are our kinships [and] the organization of our families,” says Henrich, of Harvard University. “One particular strand of Christianity … got obsessed with this and altered the direction of European history.”

But behavioral economist David Huffman of the University of Pittsburgh urges caution in interpreting the new results. “I’m pretty convinced that they’re finding these correlations,” he says. “I’m just not fully convinced about the causal story from kinship ties to all these other [psychological] variables.”

Across the globe, much variation exists among different societies’ psychological beliefs and behaviors. But in general, individuals in European countries and other countries of British descent tend to be more individualistic and independent and less conforming and obedient. These societies are often described today as Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic, or WEIRD for short (SN: 11/18/15). (Henrich coined the acronym in a seminal 2010 study in Behavioral and Brain Sciences).

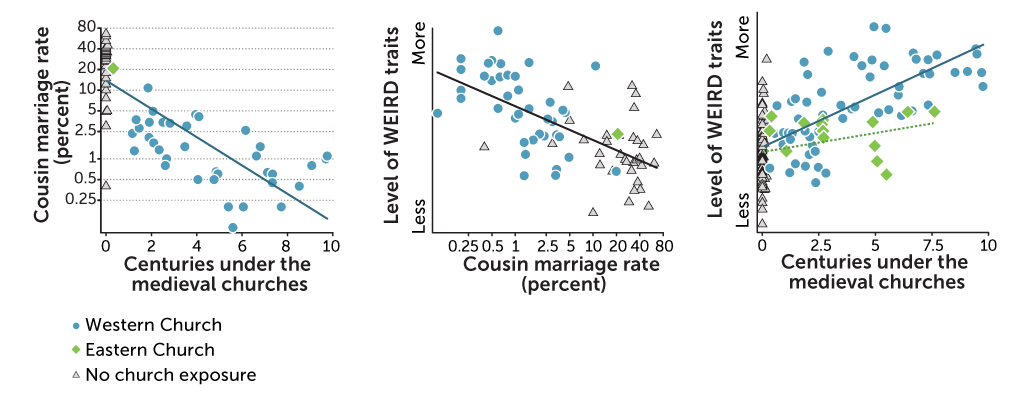

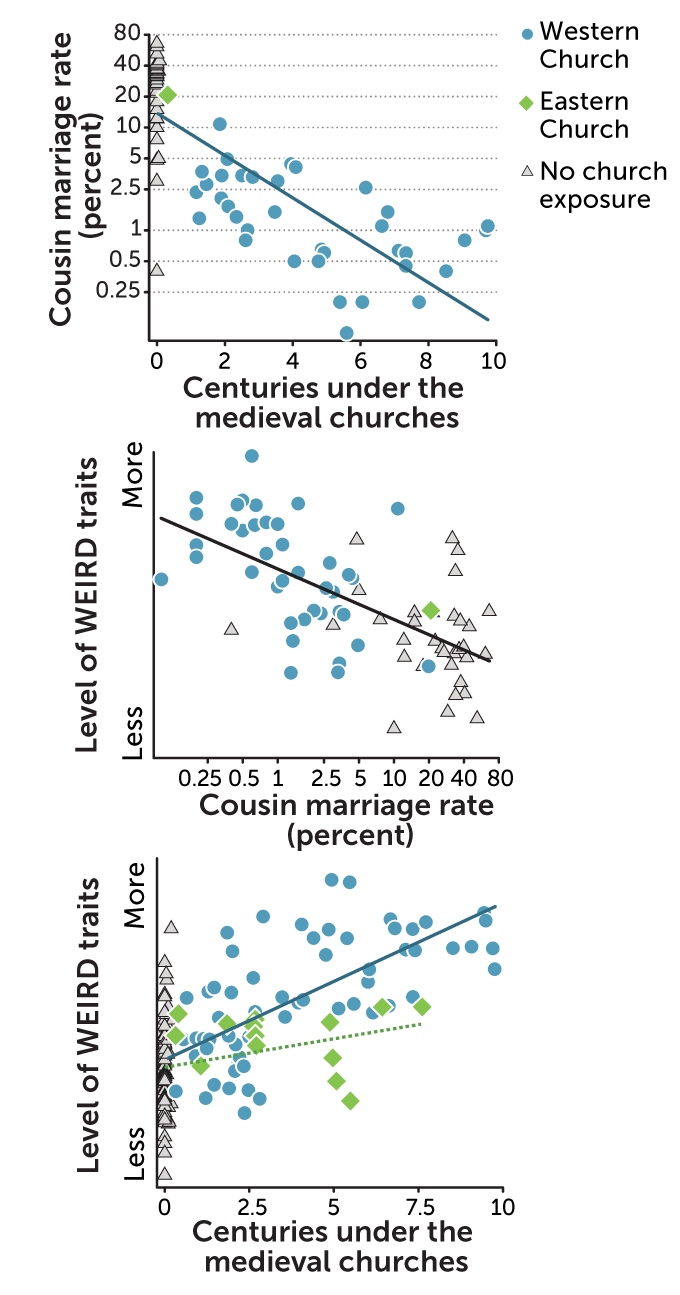

To understand how that Western mind-set might have emerged, Henrich’s team started by mapping the worldwide spread of that branch of Christianity, known as the Western Church, prior to the year 1500, when the marriage program reached its height. The team then zoomed in on the spread of bishoprics, or church administrative centers, across 440 regions in 36 European countries from 550 to 1500. That spread was mapped alongside exposure to the Eastern Church, which evolved into the Orthodox Church and did not adopt such strong taboos against “incest.”

Next, the researchers assessed how varying levels of exposure to the church and its family policies influenced the strength of community- and family-based institutions. For a qualitative approach, the authors used an existing anthropological and historical database of 1,291 populations observed before industrialization. By homing in on elements of family structure, such as marriages between cousins, habitation patterns and presence or absence of polygamy, the team showed that “kinship” — close ties with an extended clan beyond just immediate family — decreased in areas exposed to the church.

When the researchers zoomed in on rates of marriage between cousins, they found that for each 500 years a country spent under the influence of Western Church, this type of marriage dropped by 91 percent.

Lastly, the scientists evaluated that transformation in family structure alongside changes in psychological beliefs and behaviors. Drawing on existing data sources on 24 psychological metrics, such as individualism, creativity, conformity, honesty and trust, the researchers found that the longer a population was exposed to the Western Church, the higher its individualism, nonconformity and trust of strangers.

This interplay between history, family structure and psychology affects modern times, the authors say. In Italy, for example, the Western Church’s influence was limited to the northern and central portions of the country until well into the Middle Ages. Data based on Vatican records show that, consequently, marriages between first cousins were almost nonexistent in the north, but accounted for 3.5 to just over 5 percent, on average, of all unions in the far south from 1910 to 1964, the researchers found.

What’s more, the country’s average blood donation rate — a proxy for trust of strangers — equaled about 28 bags of blood for every 1,000 people, according to data from 1995. But the authors found, for instance, that a doubling of the rate of first cousin marriages in a given region was linked to a decline in blood donations by about 8 collection bags per 1,000 people, suggesting more distrust of strangers among people there. Similarly, Italians from areas with higher rates of cousin marriages were more likely than other Italians to distrust banking institutions, preferring instead to take loans from family and friends and keep money in cash.