Out-of-body experiments show kids’ budding sense of self

Children as young as age 6 have body awareness needed to identify with avatar of themselves

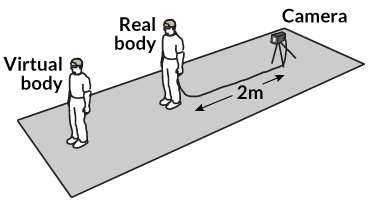

SEEING ME A sense of being a self in one’s own body develops in phases over many years, beginning by age 6, a new study finds. Researchers studied kids and adults who felt a touch on their actual backs as they saw a virtual version of themselves touched on the back with a stick. Here, a 5-year-old girl models a virtual reality device used in the study.

D. Cowie

Kids can have virtual out-of-body experiences as early as age 6. Oddly enough, the ability to inhabit a virtual avatar signals a budding sense that one’s self is located in one’s own body, researchers say.

Grade-schoolers were stroked on their backs with a stick while viewing virtual versions of themselves undergoing the same touch. Just after the session ended, the children often reported that they had felt like the virtual body was their actual body, says psychologist Dorothy Cowie of Durham University in England. This sense of being a self in a body, which can be virtually manipulated via sight and touch, gets stronger and more nuanced throughout childhood, the scientists report March 22 in Developmental Science.

By around age 10, individuals start to report feeling the touch of a stick stroking a virtual body, denoting a growing integration of sensations with the experience of body ownership, Cowie’s team finds. A year after that, youngsters still don’t display all the elements of identifying self with body observed in adults. During virtual reality trials, only adults perceived their actual bodies as physically moving through space toward virtual bodies receiving synchronized touches.

This first-of-its-kind study opens the way to studying how a sense of self develops from childhood on, says cognitive neuroscientist Olaf Blanke of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne. “The new data clearly show that kids at age 6 have brain mechanisms that generate an experience of being a self located inside one’s own body.” He suspects that a beginner’s version of “my body is me” emerges by age 4.

A limited form of self-identification is present even from birth, suggests cognitive neuroscientist Matthew Longo of Birkbeck, University of London. Longo and others have found that newborns track another baby’s videotaped face being stroked in time with touches to their own faces. Kids recognize their own bodies and images in mirrors by around age 2.

Strikingly, the new study shows that different components of identifying one’s self with an avatar appear at progressively older ages, Longo says. Kids probably can’t embody a virtual avatar without a solid sense of self-recognition in the first place, says psychologist Andreas Kalckert of the University of Reading Malaysia. Careful questioning of children is needed to ensure that they have grasped the nature of a virtual experience, he says.

Cowie’s group studied an effect called the full-body illusion. Participants stood in place while wearing a head-mounted virtual reality device. An experimenter stroked each volunteer’s back for two minutes, while the device played either a live feed of the session or a video of the volunteer being given out-of-sync strokes. The back of a participant’s virtual body being stroked appeared two meters in front of the participant.

On questionnaires administered after each virtual trial, the 31 adult participants reported a strong tendency to experience a virtual body as their own when strokes were delivered in synchrony, but not when strokes were mistimed. Adults typically reported feeling a stick’s touch on their virtual counterparts.

After an out-of-body experience, adults were asked to close their eyes and take small steps backward for 1.5 meters before returning to their starting point with regular strides. They typically stopped much closer to their virtual bodies’ location than to their initial location, an indication that they had identified more closely with their virtual bodies than their actual ones. That’s consistent with reports of virtual body swapping by adults (SN: 6/5/10, p. 10).

The researchers also studied 22 children, ages 6 and 7, and 25 more between ages 8 and 11. The youngest group reported nearly as great a sense of identifying with a virtual body as adults did. To Cowie’s surprise, 6- to 7-year-olds also reported a modest out-of-body tendency when shown non-synchronized touches. At that age, kids may have difficulty distinguishing between in-sync and out-of-sync touches to a virtual body, she suggests. In earlier studies, 6- to 7-year-olds, like adults (SN Online: 11/10/11), felt like a rubber hand was their own when a visible fake hand and their hidden hand were simultaneously stroked. Perception of the whole body may be more complex than perception of body parts, she says.

Older children identified slightly less with a virtual body than 6- to 7-year-olds did. Brain and body changes during middle childhood may temporarily intensify awareness of physical sensations, thus lowering susceptibility to the full-body illusion, Cowie suggests.

Cowie regards the new findings as a first step toward developing virtual reality learning programs geared to kids’ understanding of their own bodies. “Children may be able to learn biology by virtually traveling through a body or to play immersive chess games,” she says.