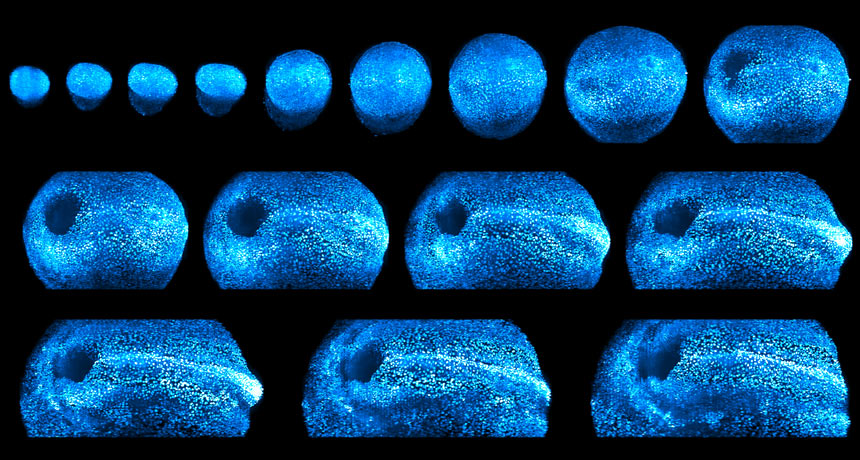

See these dazzling images of a growing mouse embryo

A new microscope lets scientists peek into the mysterious process of mammalian development

LIGHT THE WAY A new microscope uses laser light to image growing mammal embryos. Scientists used the instrument to track a mouse embryo (seen in false color) as it developed over two days.

K. McDole et al/Cell 2018