Your fear is written all over your face, in heat

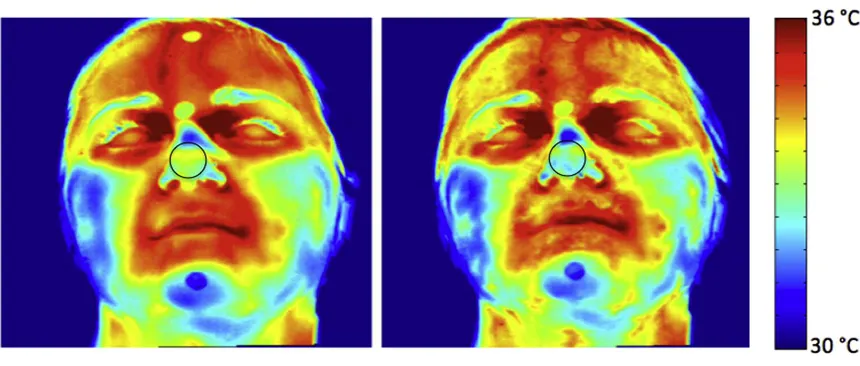

CHILLING EFFECT Face temperature plummets when a person is startled by a loud noise. In this before-and-after image, cooling shows up as more yellow on the forehead and mouth area after being startled (right) and more blue on the nose.

A. Di Giacinto et al/Neuroscience 2013

What gets us hot can be so revealing. For me, the slightest anxiety or excitement can trigger a warm spread across my face. I can feel the blood rushing up my neck and into the thousands of tiny capillaries across my cheeks. I’ve worn scarves or turtlenecks to job interviews, weather be damned, to keep my burning red neck from betraying my nerves.

And the opposite can be true. Have you ever seen someone truly blanch? Given a real fright, the blood can literally drain from a person’s face, leaving a white mask. This all happens thanks to the autonomic nervous system, the fight-or-flight control system. Faced with danger, it tells blood vessels to pinch off the flow to the face and extremities, sending more blood to the muscles and body core so you’ll be pumped up for either the flight or the fight.

Heat-sensing cameras can pick all this up, and in way more detail than my scarf could hide. Our nervous systems are constantly chugging away, largely out of our conscious control, tweaking our blood flow for every emotion. Just think of all the tiny wafts of heat flowing across your face as you negotiate with your boss, or talk to your lover. Feeling a bit anxious? Guilty? Stressed? Sexually aroused, perhaps? There’s a researcher out there with a thermal camera that can detect each of those.

Even post-traumatic stress disorder may show up in your face’s heat map. In a pilot study of bank tellers who have been robbed, a team of researchers in Italy reports in the April 25 Neuroscience that tellers with mild PTSD have amped-up fear responses that show up in their facial heat signature.

Recording thermal video of 20 bank tellers who had been robbed at gunpoint in the last 18 months, Arcangelo Merla and colleagues at the University of Chieti carried out a classic fear conditioning experiment. They showed the tellers a series of happy, neutral or angry faces, and on the fifth face: Blammo! A blast of loud white noise startled the tellers, and a video camera recorded their face’s heat as they learned to associate the face with the scary noise. The idea here is that people with PTSD have a heightened startle response in these kinds of situations.

Some of the blood drained out of everyone’s face when they were startled; that’s normal. Half the tellers had been clinically diagnosed with mild PTSD; the other half had no symptoms. Those with PTSD cooled off more, by up to 2 degrees Celsius, and took longer to recover than those without.

It’s the tip of the nose that really gives it away. “You have to consider that this is purely a fight or flight response,” Merla says. Blood is rushing away from the entire outer layer of the body, not just the face, to fuel the muscles. But the temperature of the tip of the nose, already kind of hanging out there barely keeping itself warm, is particularly sensitive to emotion and stress.

Here’s another thermal image from a paper of Merla’s showing a child’s nose tip cooling off when he feels guilty for breaking a toy. In a time sequence, the toy breaks at the third image, and the nose gets cooler (more purple in the thermal image). As he is soothed (far right), his nose warms back up and becomes more orange:

Merla’s thermal imaging of PTSD patients could eventually help to identify mild PTSD and to monitor how well treatments are working. But there are lots of other possible uses of thermal scans. The military, police or security guards could heat-map people’s faces to see whether they’re anxious, for example, which might mean they’ve got something to hide (think airport security). One of the main benefits is that you can scan people from a distance, reading their emotional state without attaching any electrodes — even without them knowing you’re doing it, which in the wrong hands could be pretty creepy.

It’s a great tool for studying emotions, though, and could even work its way into consumer technology. Merla says he has patented methods to use thermal facial imaging to control robotics and car devices according to the user’s psychological and physiological state.

“A variety of groups are now using thermal monitoring to study social interactions in humans and in other animals,” says David Perrett of the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, who studies the emotional cues hidden in human faces. Merla is trying his methods out on apes, and one of Perrett’s studies found that women’s faces heat up like a torch when touched by a man, even in a nonsexual situation. And similar to electrical lie detectors that rely on skin’s sweating response, thermal images can also reveal deception.

“Just like the lie detectors beloved of spy films, the new scanning technique is going to be subject to the same limitations,” Perrett says. You could “beat” a thermal system in the same ways people trick lie detectors: by practicing the questions or situation beforehand to train the body not to respond, or by purposely producing a “lie” reaction (or “spurious arousal”) to throw off the baseline.

That’s more effort than most people will go to. For the rest of us, just remember: Your lips can tell a lie, but your face will show.

Follow me on Twitter: @GoryErika