Thank insects and microbes that we aren’t over our knees in feces

The large tunneling dor beetle can bury poop twice as fast as its smaller neighbors.

Riikka Kaartinen

Have you ever paused to wonder why we’re not all drowning in poop? Well, you should. After all, in the United States alone, cows produce 900 billion kilograms of poop per year. In Finland, 1 million cattle produce about 4 billion kilograms of dung per year, enough to make a cube 160 meter high and comfortably bury the Statue of Liberty. That’s just cows. It’s not counting the human waste. Take a moment to imagine how that might pile up.

On second thought, don’t do that.

But what takes care of all this poop? Why aren’t we over our knees in feces? How much do animals take care of, and how much is just drying out in the sun?

To find out, the authors of a new study published in the November Ecology harnessed the power of citizen scientists. And together they learned that we can thank beetles, microbes and dehydration to thank for eliminating our many eliminations.

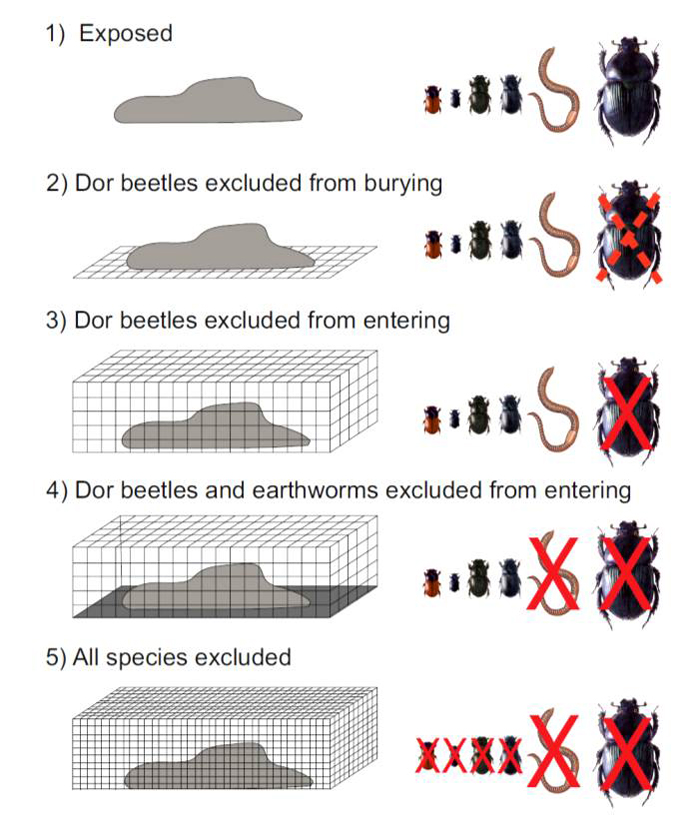

Tomas Roslin of the University of Helsinki and colleagues went to 4H clubs around Finland and got 79 student volunteers to collect 20 liters of cow pats from 73 farms all over the country. Each volunteer then measured the poop out into 15 standard cow pats of 1165 grams. Five of the pats served as “bait” pats, to measure what beetles and worms were doing in the area.

Let us all pause a moment to admire the dedication of volunteers who weighed out cow pats for science.

The scientists and citizen scientists ended up with a total of 733 cow pats in 73 farms, measured six times each. All the cow pats lost weight over time, the result of microbes and water evaporation. Between 61 and 77 percent of the cow pats’ weight loss could be accounted for with evaporation and bacteria, and 13 percent of the weight loss was the result of invertebrates.

And the biggest invertebrate poop eater in Finland was the large tunneling dung beetle (the dor beetle, in the genus Geotrupes). When the cow pats were protected from dor beetles, they ended up substantially larger. Dor beetles accounted for 61 percent of all the invertebrate decomposition. Other types of invertebrates, like worms and other beetles, also played a role.

Latitude also played a part. The further north a cow pat was, the slower it decomposed. And of course, a cow pat is a lot heavier when it’s wet. When it had been raining, the cow pats were nearly 100 grams heavier.

So when you think next about why aren’t drowning in poo, tip your hat to evaporation, microbes and insects like the dung beetle.