How COVID-19 created a perfect storm for a deadly fungal infection in India

More than 31,000 cases of mucormycosis have been reported as of June 11

Doctors in Allahabad, India, perform surgery on a mucormycosis patient on June 5. The lethal fungal infection, which typically affects the sinuses and facial tissues, can also invade the brain.

Ritesh Shukla/Getty Images

As India reels from a devastating second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, a new horror is plaguing people there. Some COVID-19 patients “go home only to come back to the hospital with a damaged nose, swollen cheeks and so on,” says SP Kalantri, a physician at the Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences in Sevagram, a small town in the state of Maharashtra.

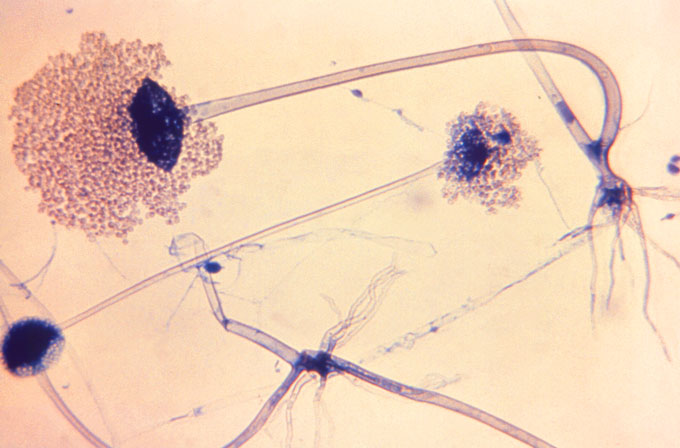

The cases aren’t unique to Kalantri’s hospital. Medical facilities across the country are seeing a surge in people who have recovered from COVID-19 and are now being preyed upon by a rare fungal infection called mucormycosis. The fungus can invade the nasal cavity and the sinuses and, in some cases, even reach the brain, turning the affected areas black. Colloquially dubbed black fungus, an infection can maim patients, and kills up to half of those who contract it, researchers reported June 4 in Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Since April, mucormycosis infections have skyrocketed across India; more than 28,000 cases had been officially reported as of June 7. Of those, 86 percent were COVID-19 patients. Local media reports in India now estimate that as of June 11, cases had reached more than 31,000. At St. John’s Medical College Hospital in Bangalore, “in the pre-COVID period, we had approximately 30 patients per year” with the infection, says Sanjiv Lewin, chief of medical services. But in a recent two-week period, “we had a sudden surge of 63 patients.”

People with COVID-19, especially those that end up in an intensive care unit, already are vulnerable to secondary infections. Other countries have reported a smattering of post–COVID-19 fungal infections, including Oman, which on June 15 reported its first mucormycosis infections in COVID-19 patients. “There have been some cases reported in the United States, but they have been very few,” says Stuart Levitz, an attending physician at the University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center in Worcester. However, no country matches the sheer number of black fungus cases being reported in India right now.

Here’s how a perfect storm of conditions came together to create the country’s rash of black fungus infections.

Fungus among us

Mucorales, the group of fungi that includes molds responsible for mucormycosis, is ubiquitous in hot and humid climates like India. So even before the pandemic, the estimated rate of these fungal infections was much higher in India than any place else in the world.

“The environment has such amount of spore, that when you give it a fertile ground, it becomes a problem,” says Arunaloke Chakrabarti, a medical mycologist at the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research in Chandigarh, India.

India typically has 140 cases of mucormycosis per million people, he and a colleague estimated in a March 2019 study in the Journal of Fungi. “That’s 70 times that of the Western world,” Chakrabarti says. In comparison, there are about 3 cases per million people in the United States, the researchers estimated.

Despite the ubiquity of these fungal spores in India, infections among healthy individuals are quite rare. But here’s where other factors of this perfect storm come into play.

Fertile ground

People with uncontrolled diabetes are at a high risk of contracting the fungal infection, studies have shown. That’s because as blood sugar levels spike, the pH of blood turns acidic, creating a favorable environment for the fungus to thrive. Diabetes “overshadows all the other risk factors,” Chakrabarti says.

Given India’s reputation as the diabetes capital of the world — with an estimated 77 million diabetics — that’s bad news. “Every eighth person admitted to the hospital either [has] diabetes or developed high blood glucose during the hospital stay,” Kalantri says.

So India already was a fertile ground for mucormycosis infections. Then the pandemic hit. Desperate for treatments, doctors and families have scrambled to get patients one of the few treatments for COVID-19: steroids. Studies have shown drugs such as dexamethasone can reduce the risk of death for severely ill COVID-19 patients (SN: 9/2/20).

“The recommendation is very clear and crisp: eight milligrams of dexamethasone only for 10 days and only in hypoxic patients,” Kalantri says. When administered at the correct time and in the right dosage, steroids can save lives by dampening the overreacting immune system and preventing inflammation in the lungs.

But given too early in an infection, when the body is trying to fight off the coronavirus by itself, steroids can be counterproductive and can hamper the body’s ability to rein in infections, leaving it vulnerable to other secondary infections. Desperation during India’s second surge of the pandemic has led to excessive and indiscriminate use of the drugs, which can be bought over the counter (SN: 5/9/21). “The message that went through the media to the lay public as well as to the regular doctor is probably that steroids are the only thing which helps, so as soon as they made a diagnosis of COVID, they gave steroids,” Lewin says.

And that exacerbated the risk for fungal infections. “Gross and irrational abuse of steroids and high glucose levels created a perfect milieu for the fungus to grow, thrive and destroy the tissues,” Kalantri says.

A July 2021 study in the Indian Journal of Ophthalmology that looked at 2,826 mucormycosis patients in India supports that conclusion. The research found diabetes and the use of steroids to be the “most important predisposing factors” for developing post–COVID-19 black fungus infections. Still, Kalantri says, “this isn’t the entire story.”

For instance, the novel coronavirus has been implicated in affecting insulin production, researchers reported February 3 in Nature Metabolism. “COVID virus itself damages the beta cell of the pancreas, which then hinders insulin production … so the blood sugar goes further high,” Chakrabarti says.

What’s more, several experts have also pointed that the rampant use of antibiotics in general could have helped the fungus gain entry. “By getting rid of bacterial flora in the sinuses and the nasal cavity, if the fungi that cause mucormycosis gets into the sinuses, you don’t have competition from the bacteria and so it may help the fungus gain a foothold,” Levitz says.

For now, it is difficult to pinpoint all of the factors responsible for India’s rising fungal infections. But the ongoing crisis provides an opportunity for epidemiological investigations to find answers and hopefully help in preventing future outbreaks. In the meantime, doctors are scrambling to do whatever they can to help people suffering now.

Treatment troubles

The good news is that, while a black fungus infection can be deadly, treatments do exist.

Liposomal amphotericin B, the primary drug used for treatment, can stop the fungus from growing and spreading to other tissues, and surgery can remove the affected tissue. But getting this treatment underway hinges on a timely diagnosis, which can be difficult to make in a resource-starved setting.

What’s more, because of the infection’s ability to affect numerous types of tissue, “you need multi-specialty teams of ophthalmologists, [ear, nose and throat] surgeons, physicians, with a neurosurgeon on standby,” Lewin says. In an already overwhelmed health care system, a team like that can be difficult to assemble. And the antifungal drug is now also hard to come by as demand has swiftly outpaced supply. Even if the drug is available in the open market, it is extremely cost-prohibitive for most Indians.

“You have to spend 30,000 rupees [the equivalent of $400] a day on the drug alone, and it doesn’t include the cost of hospitalization, CT scans, surgery, monitoring, etcetera…. Ninety-nine percent of Indians won’t be able to afford that,” Kalantri says. Even in sophisticated, tertiary-care hospitals, the situation is bleak. “I have six ampules of amphotericin B presently with me. Six! And I’ve got presently 36 patients in my ward,” Lewin says. “Without amphotericin, I am in deep trouble because the infection will continue to spread, blind my patients, even kill my patients.”

While new cases of COVID-19 in India have dropped from their peak in May to about 60,000 a day now, fungal infections continue to add up. But there is some hope. For one, the Indian government has stepped in to ramp up domestic production of liposomal amphotericin B and to facilitate importation of the drug. One doctor tweeted, “Last couple of days, few of our patients getting their full dose. So something seems to be working for now.” The long-term hope, however, hinges on ending the COVID-19 pandemic, in whose shadow the fungus has thrived.

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.