New fossils are redefining what makes a dinosaur

Defining what’s unique about these ‘fearfully great lizards’ gets harder with new finds

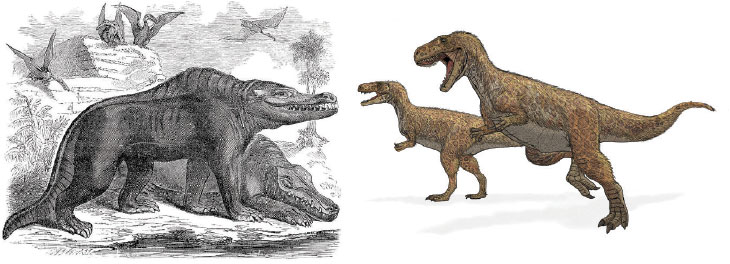

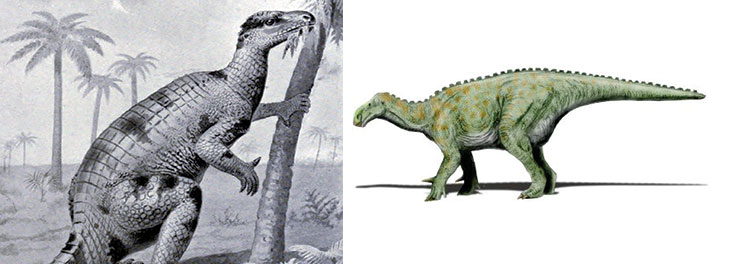

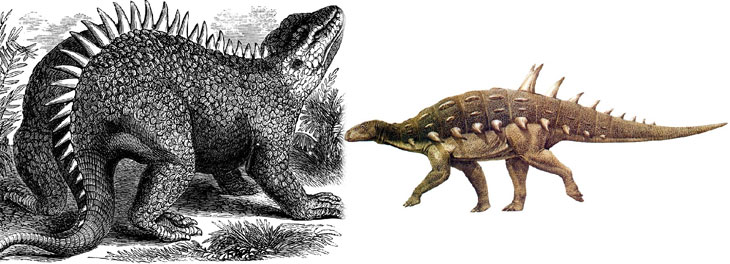

BEASTLY BREAKOUT Fossil finds have pushed aside old views of dinos, like the 1853 beasts in London's Crystal Palace Park (background).

Nicolle Rager Fuller

![]() “There’s a very faint dimple here,” Sterling Nesbitt says, holding up a palm-sized fossil to the light. The fossil, a pelvic bone, belonged to a creature called Teleocrater rhadinus. The slender, 2-meter-long reptile ran on all fours and lived 245 million years ago, about 10 million to 15 million years before scientists think dinosaurs first appeared.

“There’s a very faint dimple here,” Sterling Nesbitt says, holding up a palm-sized fossil to the light. The fossil, a pelvic bone, belonged to a creature called Teleocrater rhadinus. The slender, 2-meter-long reptile ran on all fours and lived 245 million years ago, about 10 million to 15 million years before scientists think dinosaurs first appeared.

Nesbitt, a paleontologist at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, tilts the bone toward the overhead light, illuminating a small depression in the fossil. The dent, about the size of a thumbprint, marks the place where the leg bone fit into the pelvis. In a true dinosaur, there would be a complete hole there in the hip socket, not just a depression. The dimple is like a waving red flag: Nope, not a dinosaur.

The hole in the hip socket probably helped dinosaurs position their legs underneath their bodies, rather than splayed to the sides like a crocodile’s legs. Until recently, that hole was among a handful of telltale features paleontologists used to identify whether they had their hands on an actual dinosaur specimen.

Another no-fail sign was a particular depression at the top of the skull. Until Teleocrater mucked things up. The creature predated the dinosaurs, yet it had the dinosaur skull depression.

The once-lengthy list of “definitely a dinosaur” features had already been dwindling over the past few decades thanks to new discoveries of close dino relatives such as Teleocrater. With an April 2017 report of Teleocrater’s skull depression (SN Online: 4/17/17), yet another feature was knocked off the list.

Today, just one feature is unique to Dinosauria, the great and diverse group of animals that inhabited Earth for about 165 million years, until some combination of cataclysmic asteroid and volcanic eruptions wiped out all dinosaurs except the birds.

“I often get asked ‘what defines a dinosaur,’ ” says Randall Irmis, a paleontologist at the Natural History Museum of Utah in Salt Lake City. Ten to 15 years ago, scientists would list perhaps half a dozen features, he says. “The only one to still talk about is having a complete hole in the hip socket.”

The abundance of recent discoveries of dinosauromorphs, a group that includes the

dinosaur-like creatures that lived right before and alongside early dinosaurs, does more than call diagnostic features into question. It is shaking up long-standing ideas about the dinosaur family tree.

To Nesbitt, all this upheaval has placed an even more sacred cow on the chopping block: the uniqueness of the dinosaur.

“What is a dinosaur?” Nesbitt says. “It’s essentially arbitrary.”

Yesterday’s diagnostics

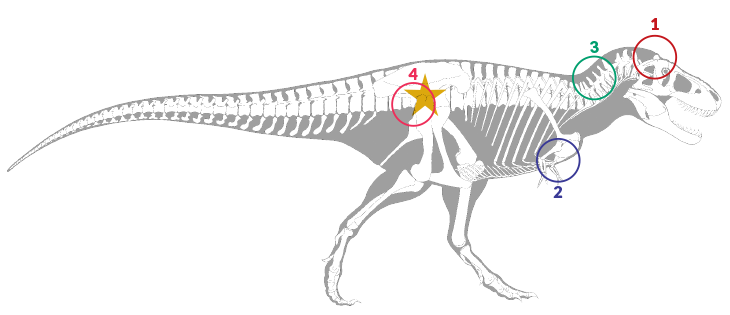

![]() Today, only one fossil feature can be attributed solely to members of Dinosauria: a complete hole in the hip socket.

Today, only one fossil feature can be attributed solely to members of Dinosauria: a complete hole in the hip socket.

Several others, including the four below, are no longer surefire dinosaur signs:

1. Until Teleocrater came along, only dinosaurs were known to have a deep depression at the top of the skull, an attachment site for some jaw muscles probably related to bite strength.

2. Dinosaurs and some other dinosauromorphs such as Silesaurus opolensis have an enlarged crest on the upper arm bone where muscles attached.

3. Along with dinosaurs, dinosauromorphs S. opolensis and Asilisaurus kongwe may have had epipophyses, bony projections at the back of the neck vertebrae.

4. An extra (fourth) muscle attachment site, called a trochanter, at the point on the femur that meets the hip is also found in dinosauromorph Marasuchus lilloensis.

Sources: S.J. Nesbitt et al/Nature 2017; S.L. Brusatte et al/Earth-Science Reviews 2010

Shared traits

Shared traits

In 1841, British paleontologist Sir Richard Owen coined the term “dinosaur.” Owen was contemplating the fossil remains of three giant creatures — a carnivore named Megalosaurus, the plant-eating Iguanodon and the heavily armored Hylaeosaurus. These animals shared several important features with one another but not other animals, he determined. (In particular, he noted, the creatures’ giant legs were upright and tucked beneath their bodies, and each of the animals had five vertebrae fused together and welded to the pelvis.)

Owen decided the animals should be biologically classified together as their own group, or taxon. He named the group “Dinosauria” for “fearfully great lizards.”

In Owen’s day, it was a bit easier to spot similarities between fossils, says paleontologist Stephen Brusatte of the University of Edinburgh. “Back then, there were so few dinosaurs. But the more fossils you find, the patterns become more complicated,” he says. “With every new discovery, you get a different view of what features define a dinosaur. It’s nowhere near as clear-cut as it used to be.”

Dino survivors

Dino survivors

The largest extinction of species on Earth, the “Great Dying,” happened about 252 million years ago at the end of the Permian Period (SN: 9/19/15, p. 10). About 96 percent of marine species and 70 percent of land species succumbed.

In the period that followed, the Triassic, spanning 252 million to 201 million years ago, new reptilian species arose and flourished. This was the time of the dinosauromorphs, crocodylians (the ancestors of crocodiles) and, of course, the dinosaurs themselves. No one knows exactly when dinosaurs arose, although it was probably around 230 million years ago.

For tens of millions of years, the dinosaurs lived alongside numerous other reptile lineages. But at the end of the Triassic, dramatic climate change played a role in another mass extinction. Dinosaurs somehow survived and went on to dominate the planet during the Jurassic Period.

Paleontologists once assumed the dinosaurs were somehow superior, with physical features that helped them outcompete the other reptiles. “But that’s not borne out by new dinosaur relatives,” Nesbitt says. Dinosaurs and dinosauromorphs, researchers found, were very similar. The new bonanza of dinosauromorph fossils reveals a repeating pattern of parallel evolution, such as lengthening legs or having legs oriented directly under the body. In short, Nesbitt says, dinosaurs “are not doing anything different than their closest relatives.”

On the heels of those discoveries, many paleontologists suspect that the reason for dinosaurs’ rapid expansion in the Jurassic is simply that the creatures took advantage of the sudden availability of ecological niches left behind by their long-dead cousins from the Triassic.

But that doesn’t explain why dinosaurs survived the extinction at the end of the Triassic, while their dinosauromorph cousins (and most of the crocodylians) died out. That’s a question no one yet has answered.

Maybe dinosaurs had some anatomical characteristics that helped them survive, suggests Max Langer, a paleontologist at the University of São Paulo. “But we don’t know what those features were.”

Uprooting the family tree

Uprooting the family tree

To identify the animal that left behind a fossil, paleontologists pore over the bone, noting each bump, groove and hole, measuring the length of a tibia bone or counting the digits on a forelimb. Before powerful computers were available, scientists constructed evolutionary trees by noting which species share different bumps and grooves, and assessing whether those features (also called characters) were inherited from a common ancestor, or passed along to descendants.

Langer calls that approach to phylogenetic analyses “old-fashioned.” Today, scientists use computer algorithms to help construct elaborate phylogenetic, or evolutionary, trees. But the fossil characters are still the raw data required to create those trees, and the analyses are only as good as those data. Different researchers may choose different features to consider, and may interpret the fossils differently, too. Those concerns hit home among dinosaur researchers last year, when a team proposed a fundamental reorganization of the dinosaur evolutionary tree.

For about 130 years, the basic structure of the dinosaur family tree was considered relatively stable. Dinosaurs were split into two main lines based on the shape of the hips. Both lines had the hole in the hip socket, still considered unique to all dinosaurs. One line known as the ornithischians, also had a pubis bone that pointed down toward the tail. That group includes giant herbivores such as the three-horned Triceratops and plate-armored Stegosaurus. The other line’s pubis bone pointed down toward the front, a hip shape shared by long-necked sauropods such as Brachiosaurus and by carnivorous theropods such as Tyrannosaurus rex. With those hip similarities, sauropods and theropods have long been considered closer “sister” groups, while ornithischians were seen as more distant relations.

But in March 2017, Ph.D. student Matthew Baron and vertebrate paleontologist David Norman of the University of Cambridge, along with paleobiologist Paul Barrett of the Natural History Museum in London, proposed upending that long-standing arrangement.

At the heart of their paper, published in Nature, was the observation that ornithischians have been somewhat overlooked in previous phylogenetic analyses. The herbivorous ornithischians were a really diverse bunch, with a spectacular array of frills and armors and horns and crests.

So the researchers decided to see how different the family tree would look if an analysis included many more ornithischian species. The team incorporated some 457 different fossil characters from 74 species of all kinds of dinosaurs and dinosaur relatives (SN: 4/15/17, p. 7).

The newly constructed tree might as well have been from a whole different forest. It shuffled the three big groups around, putting ornithischians and theropods together into a new group and suggesting that sauropods had split off earlier.

Baron and his coauthors found that the ornithischians had more than 20 features in common with predatory theropods.

The paper made a splash, but many paleontologists were skeptical. The bar to revise a tree that had stood decades of previous phylogenetic analyses ought to be pretty high, Brusatte says.

Indeed, one point arising from the study was just how subjective phylogenetic analyses can be, Irmis says. Which species a study includes clearly affects how the tree turns out, he says. Plus, he adds, “a slight difference in how one person interprets the anatomy of a fossil or a particular character can make a cumulatively huge difference.”

Langer, Brusatte and several paleontologist colleagues decided to tackle the character interpretation part of the problem head on. “When the paper came out, there was this flurry of excitement,” Brusatte says. “But a lot of us noticed right away that there wasn’t a huge amount of description about the characters.” The concern was that, if the fossils weren’t carefully examined and the characters properly assessed, those errors could dramatically skew the results.

So the researchers divvied up the task of traveling around the world to visit the fossils included in the original paper and to reassess all 457 characters described — in person. “It was essentially a replication study,” Brusatte says.

The team went in expecting to cast doubt on the tree created by Baron, Norman and Barrett — or possibly to completely debunk it. But that didn’t exactly happen.

Langer, Brusatte and their coauthors reported last November in Nature that their analyses showed that the original, 130-year-old evolutionary tree was still the best fit to the dinosaur dataset used by Baron’s team.

But, they found, the original tree wasn’t that much more likely to be correct than the newly described tree. “This is the thing that really blew us away: It wasn’t actually a statistically significant result,” Brusatte says. In fact, the often-accepted tree wasn’t even that much more likely than an older, third arrangement of the tree that grouped ornithischians closer to the other herbivores in the family, the long-necked sauropods, and left the fierce theropods as the outliers.

“There is currently great uncertainty about early dinosaur relationships and the basic

structure of the dinosaur family tree,” the researchers concluded. “It seems that the flood of new

discoveries over the past decades has revealed unexpected complexity.”

Brusatte adds: “We shouldn’t rewrite the textbooks just yet. But we’ve taken what we thought was a certainty and turned it into a mystery — and a big mystery, at that.”

Twisting tree

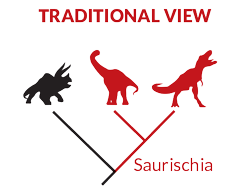

The dinosaur family tree has three main branches: herbivorous ornithischians, long-necked sauropods and fierce theropods. Their relationships may be shifting.

Source: M.C. Langer et al/Nature 2017

Based on hip shape, sauropods and theropods were thought to be more closely related to each other than to ornithischians.

A March 2017 analysis of a longer list of ornithischian species concluded that ornithischians and theropods are closely related.

A November 2017 analysis upheld the traditional view but found that other arrangements are almost equally likely —including a view that clusters herbivorous ornithischians and sauropods together.

Catch-22

Catch-22

How the different dinosaur groups are related to one another may seem like insider baseball, Nesbitt says. But the evolutionary tree is the common ground, the framework within which researchers can discuss dinosaur evolution, dinosaur origins and what binds all dinosaurs together. “It makes it difficult to ask questions about how features are evolving if we can’t have some agreed-upon taxonomy,” he adds.

Similarly, without an agreed-upon evolutionary tree, it’s hard to know which anatomical features to follow through the tree — such as any that might have helped dinosaurs survive the end-Triassic extinction. Each arrangement of the evolutionary tree seems to highlight different features as being particularly important, Langer says. “If you don’t know how the tree is arranged, you can’t say which feature characterizes [dinosaurs].”

The thorny problem revolves around which to tackle first: How to define a dinosaur or how to redraw the dinosaur family tree?

But Langer suggests the answer, as always, is to return to the fossils. In the paper by Langer and his coauthors, they make a plea for researchers to do the mundane work. “We proposed that we need more … anatomical descriptions and definition of characters,” Langer says. “It’s boring to do, but people have to do more of this.”

Finding Teleocrater

Finding Teleocrater

As Nesbitt cradles the Teleocrater pelvic bone, he turns to a tall cabinet of wide, shallow drawers. He slides open a drawer filled with dozens of carefully labeled boxes, each holding one or more bones from Teleocrater, collected during a 2015 expedition to Tanzania’s Ruhuhu Basin.

The first known fossils of Teleocrater rhadinus, to date the only species of the genus Teleocrater, were actually discovered in the 1930s. But those fossils — a few bits of vertebrae, pelvis and limb — languished unidentified in London’s Natural History Museum for several decades.

The Ruhuhu Basin, an area dating to between 247 million and 242 million years ago, was a popular place in the Triassic. The site contains abundant fossils, diverse assemblages of Triassic animals including relatives of crocodylians, giant-headed amphibians and ancient relatives of modern mammals called cynodonts.

In 2010, Nesbitt described a species of dinosauromorph from the Ruhuhu Basin dubbed Asilisaurus kongwe. But on his 2015 expedition, he was hoping to find more evidence that would help identify the mysterious Teleocrater — perhaps even a skull.

He hit pay dirt: His team found a bone bed containing at least three Teleocrater individuals, including a braincase and jawbone. The skull was a particularly exciting find, because it showed the team that Teleocrater, clearly a nondinosaur from other features, had the skull depression, just like a true dinosaur.

Paleontologists tend to say that finding more fossils from early dinosaurs and their close relatives is the surest way to fill in the gaps on how the creatures evolved and to tidy up the family tree.

Nesbitt laughs. “Now we have way more fossils,” he says, “and it’s way messier.”

This article appears in the March 3, 2018 issue of Science News with the headline, “What makes a dinosaur? Defining what’s unique about these ‘fearfully great lizards’ gets harder with new fossils.”