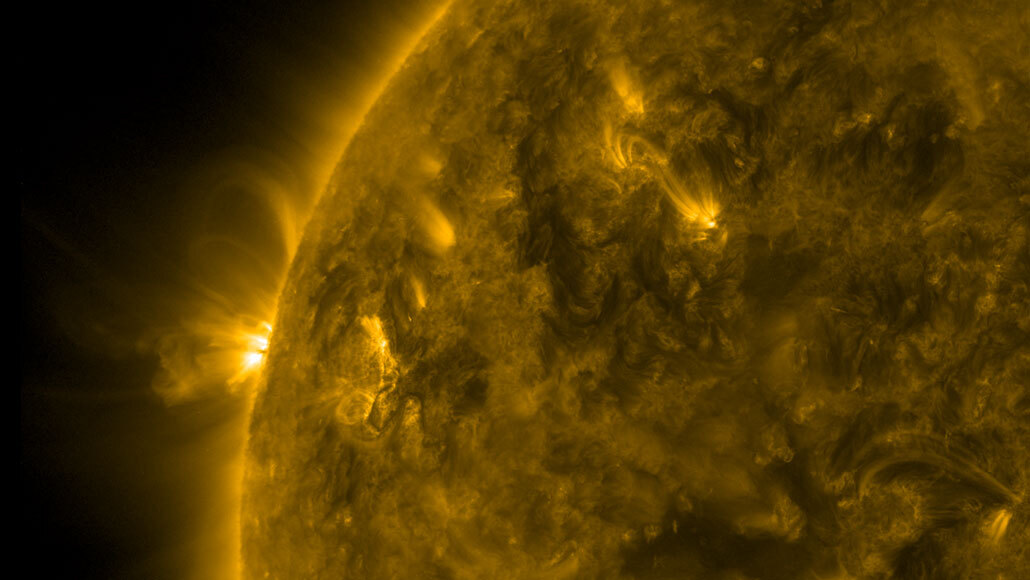

The sun’s magnetic field drives loops of plasma to fly off its surface, as shown in this image from NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory. Changes in a star’s magnetism can show up as changes in its brightness.

Solar Dynamics Observatory/GSFC/NASA

The sun might be a magnetic slacker.

A census of stars similar to the sun shows that our own star is less magnetically active than others of its kind, astrophysicists report in the May 1 Science. The result could support the idea that the sun is in a “midlife crisis,” transitioning into a quieter phase of life. Or, alternatively, it could mean that the sun has capacity for much more magnetic oomph than it’s shown in the past.

“Our sun could potentially become [as] active” as those other stars in the future, says astrophysicist Timo Reinhold of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Göttingen, Germany.

A star’s magnetism can drive dramatic outbursts like flares and coronal mass ejections, which can cause chaos on orbiting planets (SN: 3/5/18). When these large ejections from the sun hit Earth, they can knock out satellites, shut down power grids and trigger beautiful auroras. Understanding the sun’s magnetic field is thought to be the key to predicting such outbursts (SN: 6/30/19).

Magnetic fields also can create dark sunspots and bright spots called faculae on a star’s surface. These features change over time as magnetic activity changes, altering a star’s brightness.

Astronomers have been observing the sun’s magnetism through those surface features since Galileo turned a telescope toward the sun in 1610. While the sun’s magnetic activity waxes and wanes in an 11-year cycle, our star has remained fairly calm while humans have been watching. Inferences from certain radioactive elements found in tree rings and ice cores suggest that same overall cycle of magnetic activity has held steady for the last 9,000 years.

Because other stars are so far away, tiny changes in brightness that reveal magnetic changes were hard to detect until 2009, when the Kepler space telescope launched (SN: 9/18/19). The now-defunct telescope found exoplanets by picking up on slight dips in starlight as planets orbited in front of stars (SN: 10/30/18), but the spacecraft’s data include a wealth of information on other changes in stars’ brightness.

To see how the sun’s brightness compared with its stellar kin from 2009 to 2013, Reinhold and his colleagues studied stars whose age, surface gravity, chemical makeup and temperature are similar to the sun’s (SN: 8/3/18). The team also sought stars that rotate at nearly the same rate as the sun, roughly once every 24 days.

Not every star’s rotation period was measurable, so Reinhold’s team split the stars into two groups: 365 “solarlike” stars, with rotation periods between 20 and 30 days, and 2,898 “pseudo-solar” stars, whose period could not be detected.

Surprisingly, although the stars with no detectable rotation periods looked as magnetically calm as the sun, the stars with sunlike rotations were up to five times as active.

Either something is different about those stars, Reinhold says, or the sun may go through periods of greater variability in its brightness — and thus, magnetic activity — that scientists just haven’t seen. Perhaps “the sun did not reveal its full range of activity over the last 9,000 years,” he says. “The sun is 4.5 billion years old; 9,000 years is nothing.”

Still another explanation for the finding is related to the idea that stars might stop slowing their rotation because of a midlife change in their magnetic field (SN: 8/2/19), says astronomer Travis Metcalfe of the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo.

Many stellar physicists think that stars continually lose momentum and slow their spins as they get old. But in 2016, Metcalfe and colleagues reported that Kepler was seeing stars that rotate too fast for their advanced ages. The team suggested that stars might stop their slowdowns at middle age, and that the sun is currently going through this transition.

The new result “could be the best evidence yet that the sun is in the midst of a magnetic midlife crisis,” Metcalfe says. The hyperactive stars in Reinhold’s sample appear to be slightly younger than the sun, and so may not have gone through their magnetic transition yet. The sun and the other calmer stars could already be on the other side.

“It’s super interesting either way it turns out,” Metcalfe says.