Some of the first creatures to leave the ocean and venture onto land may have done so by carrying a bit of the sea with them: Fossil trackways left on ancient tidal flats 500 million years ago hint that some ocean-dwelling arthropods, like today’s hermit crabs, hauled out onto land wearing shells. Those shells would have protected the creatures’ delicate gills from drying out and may also have held small reservoirs of seawater.

Much scientific attention has focused on the water-to-land transition that vertebrates made between 385 million and 376 million years ago (SN: 6/17/06, p. 379; 1/31/09, p. 30). But by that era, another group of creatures — arthropods, the group that today includes crustaceans, scorpions and insects — had been strolling around on land for more than 115 million years, notes James W. Hagadorn, a paleontologist at Amherst College in Massachusetts.

Ocean-dwelling arthropods would have been well equipped to survive on land, says Hagadorn. Their tough yet flexible exoskeleton would have kept the creatures from drying out quickly and provided gravity-defying strength to their legs. Despite these advantages, the creatures would have had to keep their gills moist during occasional forays on land, possibly for food, he adds. Now, he and Yale University paleontologist Adolf Seilacher suggest in the April Geology that some early arthropods sported shells to survive a lengthy excursion onshore.

“This is a pretty neat study,” says Anthony Martin, a vertebrate paleontologist at Emory University in Atlanta. “That Cambrian arthropods had some sort of behavioral adaptation for coping with times out of water is not so surprising, but for them to be using shells like hermit crabs nearly 500 million years ago is amazing,” he notes.

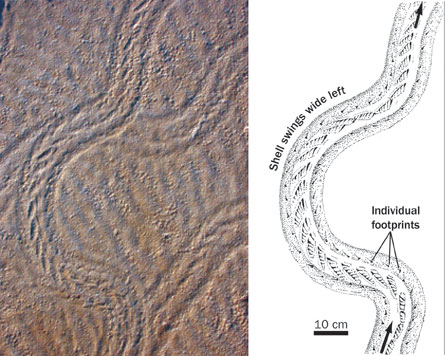

The team’s evidence includes arthropod trackways found in ancient sandstone in central Wisconsin. Some of the trackways include impressions scraped into the sand on either side of the creature’s footprints. If a trailing appendage like a tail had made those impressions, the scrapings would be similar to the tire tracks made by a truck-drawn trailer: The impressions would extend farther to the right as the creature turned left, and more to the left as the creature turned right, Hagadorn says.

But in the Wisconsin trackways, the scrapings swung farther to the left of the footprints regardless of which direction the creature was turning. Hagadorn and Seilacher speculate that the asymmetric impressions were made by a shell that the creature carried on its back like modern-day hermit crabs do. That shell would have provided a humid chamber that would allow the creatures to extend their time on land while foraging.

The trackways are asymmetrical, the researchers suggest, because the shell that the arthropod carried was coiled — probably in a right-handed spiral.

“This is an exciting find,” says Sally E. Walker, an invertebrate paleobiologist at the University of Georgia in Athens. “This opens up a whole new area of forensics” in which researchers can look for scratch marks on the outer surface of shells that indicate that they were dragged along the sand. Other scratches inside the shells might hint that they were occupied after the original shell-maker died, she notes.