People are bad at spotting fake news. Can computer programs do better?

There’s just too much misinformation online for human fact-checkers to catch it all

DECEPTION MONITORS Researchers are building online algorithms to check the veracity of online news.

Alex Nabaum

Scrolling through a news feed often feels like playing Two Truths and a Lie.

Some falsehoods are easy to spot. Like reports that First Lady Melania Trump wanted an exorcist to cleanse the White House of Obama-era demons, or that an Ohio school principal was arrested for defecating in front of a student assembly. In other cases, fiction blends a little too well with fact. Was CNN really raided by the Federal Communications Commission? Did cops actually uncover a meth lab inside an Alabama Walmart? No and no. But anyone scrolling through a slew of stories could easily be fooled.

We live in a golden age of misinformation. On Twitter, falsehoods spread further and faster than the truth (SN: 3/31/18, p. 14). In the run-up to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, the most popular bogus articles got more Facebook shares, reactions and comments than the top real news, according to a BuzzFeed News analysis.

Before the internet, “you could not have a person sitting in an attic and generating conspiracy theories at a mass scale,” says Luca de Alfaro, a computer scientist at the University of California, Santa Cruz. But with today’s social media, peddling lies is all too easy — whether those lies come from outfits like Disinfomedia, a company that has owned several false news websites, or a scrum of teenagers in Macedonia who raked in the cash by writing popular fake news during the 2016 election.

Most internet users probably aren’t intentionally broadcasting bunk. Information overload and the average Web surfer’s limited attention span aren’t exactly conducive to fact-checking vigilance. Confirmation bias feeds in as well. “When you’re dealing with unfiltered information, it’s likely that people will choose something that conforms to their own thinking, even if that information is false,” says Fabiana Zollo, a computer scientist at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice in Italy who studies how information circulates on social networks.

Intentional or not, sharing misinformation can have serious consequences. Fake news doesn’t just threaten the integrity of elections and erode public trust in real news. It threatens lives. False rumors that spread on WhatsApp, a smartphone messaging system, for instance, incited lynchings in India this year that left more than a dozen people dead.

To help sort fake news from truth, programmers are building automated systems that judge the veracity of online stories. A computer program might consider certain characteristics of an article or the reception an article gets on social media. Computers that recognize certain warning signs could alert human fact-checkers, who would do the final verification.

Automatic lie-finding tools are “still in their infancy,” says computer scientist Giovanni Luca Ciampaglia of Indiana University Bloomington. Researchers are exploring which factors most reliably peg fake news. Unfortunately, they have no agreed-upon set of true and false stories to use for testing their tactics. Some programmers rely on established media outlets or state press agencies to determine which stories are true or not, while others draw from lists of reported fake news on social media. So research in this area is something of a free-for-all.

But teams around the world are forging ahead because the internet is a fire hose of information, and asking human fact-checkers to keep up is like aiming that hose at a Brita filter. “It’s sort of mind-numbing,” says Alex Kasprak, a science writer at Snopes, the oldest and largest online fact-checking site, “just the volume of really shoddy stuff that’s out there.”

Reader referrals

Visitors to real news websites mainly reach those sites directly or from search engine results. Fake news sites attract a much higher share of their incoming web traffic through links on social media.

Substance and style

When it comes to inspecting news content directly, there are two major ways to tell if a story fits the bill for fraudulence: what the author is saying and how the author is saying it.

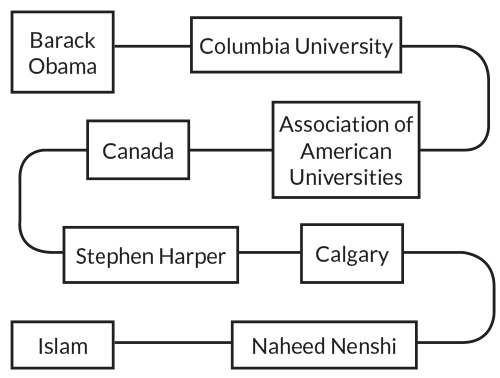

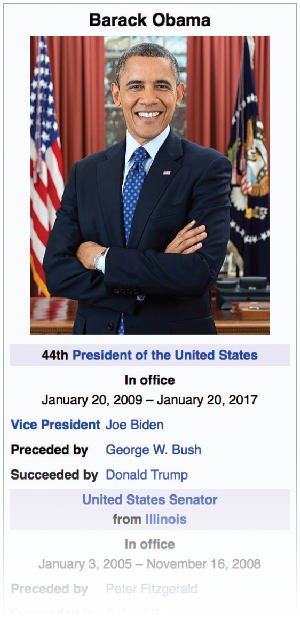

Ciampaglia and colleagues automated this tedious task with a program that checks how closely related a statement’s subject and object are. To do this, the program uses a vast network of nouns built from facts found in the infobox on the right side of every Wikipedia page — although similar networks have been built from other reservoirs of knowledge, like research databases.

Roundabout route

| An automated fact-checker judges the assertion “Barack Obama is a Muslim” by studying degrees of separation between the words “Obama” and “Islam” in a noun network built from Wikipedia info. The very loose connection between these two nouns suggests the statement is false. |

Source: G.L. Ciampaglia et al/PLOS One 2015

In the Ciampaglia group’s noun network, two nouns are connected if one noun appeared in the infobox of another. The fewer degrees of separation between a statement’s subject and object in this network, and the more specific the intermediate words connecting subject and object, the more likely the computer program is to label a statement as true.

Take the false assertion “Barack Obama is a Muslim.” There are seven degrees of separation between “Obama” and “Islam” in the noun network, including very general nouns, such as “Canada,” that connect to many other words. Given this long, meandering route, the automated fact-checker, described in 2015 in PLOS ONE, deemed Obama unlikely to be Muslim.

But estimating the veracity of statements based on this kind of subject-object separation has limits. For instance, the system deemed it likely that former President George W. Bush is married to Laura Bush. Great. It also decided George W. Bush is probably married to Barbara Bush, his mother. Less great. Ciampaglia and colleagues have been working to give their program a more nuanced view of the relationships between nouns in the network.

Verifying every statement in an article isn’t the only way to see if a story passes the smell test. Writing style may be another giveaway. Benjamin Horne and Sibel Adali, computer scientists at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y., analyzed 75 true articles from media outlets deemed most trustworthy by Business Insider, as well as 75 false stories from sites on a blacklist of misleading websites. Compared with real news, false articles tended to be shorter and more repetitive with more adverbs. Fake stories also had fewer quotes, technical words and nouns.

Based on these results, the researchers created a computer program that used the four strongest distinguishing factors of fake news — number of nouns and number of quotes, redundancy and word counts — to judge article veracity. The program, presented at last year’s International Conference on Web and Social Media in Montreal, correctly sorted fake news from true 71 percent of the time (a program that sorted fake news from true at random would show about 50 percent accuracy). Horne and Adali are looking for additional features to boost accuracy.

Verónica Pérez-Rosas, a computer scientist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and colleagues compared 240 genuine and 240 made-up articles. Like Horne and Adali, Pérez-Rosas’ team found more adverbs in fake news articles than in real ones. The fake news in this analysis, reported at arXiv.org on August 23, 2017, also tended to use more positive language and express more certainty.

Truth and lies

A study of hundreds of articles revealed stylistic differences between genuine and made-up news. Real stories contained more language conveying differentiation, whereas faux stories expressed more certainty.

| Frequently used words in legitimate news | Frequently used words in fake news | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| “think” “know” “consider” |

Words that express insight | Words that express certainty | “always” “never” “proven” |

| “work” “class” “boss” |

Work-related words | Social words | “talk” “us” “friend” |

| “not” “without” “don’t” |

Negations | Words that express positive emotions | “happy” “pretty” “good” |

| “but” “instead” “against” |

Words that express differentiation | Words related to cognitive processes | “cause” “know” “ought” |

| “percent” “majority” “part” |

Words that quantify | Words that focus on the future | “will” “gonna” “soon” |

Computers don’t necessarily need humans to tell them which aspects of fake articles give these stories away. Computer scientist and engineer Vagelis Papalexakis of the University of California, Riverside and colleagues built a fake news detector that started by sorting a cache of articles into groups based on how similar the stories were. The researchers didn’t provide explicit instructions on how to assess similarity. Once the program bunched articles according to likeness, the researchers labeled 5 percent of all the articles as factual or false. From this information, the algorithm, described April 24 at arXiv.org, predicted labels for the rest of the unmarked articles. Papalexakis’ team tested this system on almost 32,000 real and 32,000 fake articles shared on Twitter. Fed that little kernel of truth, the program correctly predicted labels for about 69 percent of the other stories.

Adult supervision

Getting it right about 70 percent of the time isn’t nearly accurate enough to trust news-vetting programs on their own. But fake news detectors could offer a proceed-with-caution alert when a user opens a suspicious story in a Web browser, similar to the alert that appears when you’re about to visit a site with no security certificate.

In a similar kind of first step, social media platforms could use misinformation watchdogs to prowl news feeds for questionable stories to then send to human fact-checkers. Today, Facebook considers feedback from users — like those who post disbelieving comments or report that an article is false — when choosing which stories to fact-check. The company then sends these stories to the professional skeptics at FactCheck.org, PolitiFact or Snopes for verification. But Facebook is open to using other signals to find hoaxes more efficiently, says Facebook spokesperson Lauren Svensson.

No matter how good computers get at finding fake news, these systems shouldn’t totally replace human fact-checkers, Horne says. The final call on whether a story is false may require a more nuanced understanding than a computer can provide.

“There’s a huge gray scale” of misinformation, says Julio Amador Diaz Lopez, a computer scientist and economist at Imperial College London. That spectrum — which includes truth taken out of context, propaganda and statements that are virtually impossible to verify, such as religious convictions — may be tough for computers to navigate.

Snopes science writer Kasprak imagines that the future of fact-checking will be like computer-assisted audio transcription. First, the automated system hammers out a rough draft of the transcription. But a human still has to review that text for overlooked details like spelling and punctuation errors, or words that the program just got wrong. Similarly, computers could compile lists of suspect articles for people to check, Kasprak says, emphasizing that humans should still get the final say on what’s labeled as true.

Eyes on the audience

Even as algorithms get more astute at flagging bogus articles, there’s no guarantee that fake news creators won’t step up their game to elude detection. If computer programs are designed to be skeptical of stories that are overly positive or express lots of certainty, then con authors could refine their writing styles accordingly.

“Fake news, like a virus, can evolve and update itself,” says Daqing Li, a network scientist at Beihang University in Beijing who has studied fake news on Twitter. Fortunately, online news stories can be judged on more than the content of their narratives. And other telltale signs of false news might be much harder to manipulate — namely, the kinds of audience engagement these stories attract on social media.

Sheeples

The majority of Twitter users who discussed false rumors about two disasters posted tweets that simply spread these rumors. Only a small fraction posted seeking verification or expressing doubt about the stories.

Juan Cao, a computer scientist at the Institute of Computing Technology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, found that on China’s version of Twitter, Sina Weibo, the specific tweets about a certain piece of news are good indicators for whether a particular story is true. Cao’s team built a system that could round up the tweets discussing a particular news event, then sort those posts into two groups: those that expressed support for the story and those that opposed it. The system considered several factors to gauge the credibility of those posts. If, for example, the story centered on a local event that a user was geographically close to, the user’s input was seen as more credible than the input of a user farther away. If a user had been dormant for a long time and started posting about a single story, that abnormal behavior counted against the user’s credibility. By weighing the ethos of the supporting and the skeptical tweets, the program decided whether a particular story was likely to be fake.

Cao’s group tested this technique on 73 real and 73 fake stories, labeled as such by organizations like China’s state-run Xinhua News Agency. The algorithm examined about 50,000 tweets about these stories on Sina Weibo, and recognized fake news correctly about 84 percent of the time. Cao’s team described the findings in 2016 in Phoenix at an Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence conference. UC Santa Cruz’s de Alfaro and colleagues similarly reported in Macedonia at last year’s European Conference on Machine Learning and Principles and Practices of Knowledge Discovery in Databases that hoaxes can be distinguished from real news circulating on Facebook based on which users like these stories.

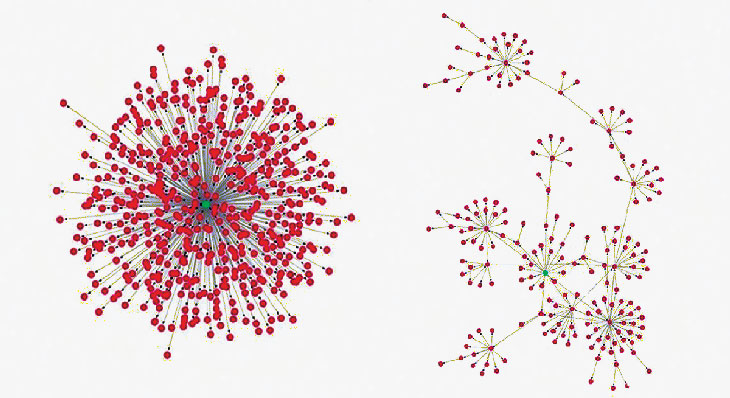

Rather than looking at who’s reacting to an article, a computer could look at how the story is getting passed around on social media. Li and colleagues studied the shapes of repost networks that branched out from news stories on social media. The researchers analyzed repost networks of about 1,700 fake and 500 true news stories on Weibo, as well as about 30 fake and 30 true news networks on Twitter. On both social media sites, Li’s team found, most people tended to repost real news straight from a single source, whereas fake news tended to spread more through people reposting from other reposters.

A typical network of real news reposts “looks much more like a star, but the fake news spreads more like a tree,” Li says. This held true even when Li’s team ignored news originally posted by well-known, official sources, like news outlets themselves. Reported March 9 at arXiv.org, these findings suggest that computers could use social media engagement as a litmus test for truthfulness, even without putting individual posts under the microscope.

Branching out

On Twitter, most people reposting (red dots) real news get it from a single, central source (green dot). Fake news spreads more through people reposting from other reposters.

Truth to the people

When misinformation is caught circulating on social networks, how best to deal with it is still an open question. Simply scrubbing bogus articles from news feeds is probably not the way to go. Social media platforms exerting that level of control over what visitors can see “would be like a totalitarian state,” says Murphy Choy, a data analyst at SSON Analytics in Singapore. “It’s going to become very uncomfortable for all parties involved.”

Platforms could put warning signs on misinformation. But labeling stories that have been verified as false may have an unfortunate “implied truth effect.” People might put more trust in any stories that aren’t explicitly flagged as false, whether they’ve been checked or not, according to research posted last September on the Social Science Research Network by human behavior researchers Gordon Pennycook, of the University of Regina in Canada, and David Rand at Yale University.

Rather than remove stories, Facebook shows debunked stories lower in users’ news feeds, which can cut a false article’s future views by 80 percent, company spokesperson Svensson says. Facebook also displays articles that debunk false stories whenever users encounter the related stories — though that technique may backfire. In a study of Facebook users who like and share conspiracy news, Zollo and colleague Walter Quattrociocchi found that after conspiracists interacted with debunking articles, these users actually increased their activity on Facebook conspiracy pages. The researchers reported this finding in June in Complex Spreading Phenomena in Social Systems.

There’s still a lot of work to be done in teaching computers — and people — to recognize fake news. As the old saying goes: A lie can get halfway around the world before the truth has put on its shoes. But keen-eyed computer algorithms may at least slow down fake stories with some new ankle weights.