A COVID-19 vaccine may come soon. Will the blistering pace backfire?

In the rush to bring vaccines to market, any misstep could erode the public’s trust

Engineers at Sinovac Biotech’s facilities in Beijing work on an experimental vaccine against the coronavirus. The company’s vaccine candidate is one of 179 being tested in lab dishes, animals and people worldwide.

NICOLAS ASFOURI/AFP/Getty Images

In January, vaccine researchers lined up on the starting blocks, waiting to hear a pistol. That shot came on January 10, when scientists in China announced the complete genetic makeup of the novel coronavirus. With that information in hand, the headlong race toward a vaccine began.

As the virus, now known as SARS-CoV-2, began to spread like wildfire around the globe, researchers sprinted to catch up with treatments and vaccines. Now, six months later, there is still no cure and no preventative for the disease caused by the virus, COVID-19, though there are glimmers of hope. Studies show that two drugs can help treat the sick: The antiviral remdesivir shortens recovery times (SN: 4/29/20) and a steroid called dexamethasone reduces deaths among people hospitalized with COVID-19 who need help breathing (SN: 6/16/20).

But the finish line in this race remains a safe and effective vaccine. With nearly 180 vaccine candidates now being tested in lab dishes, animals and even already in humans, that end may be in sight. Some experts predict that a vaccine may be available for emergency use for the general public by the end of the year even before it receives expedited U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval.

Velocity might come at the expense of safety and efficacy, some experts worry. And that could stymie efforts to convince enough people to get the vaccine in order to build the herd immunity needed to end the pandemic.

“We’re calling for transparency of data,” says Esther Krofah, executive director of FasterCures, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit. “We want things to accelerate meaningfully in a way that does not compromise safety or the science, but we need to see the data,” she says.

Getting a head start

Traditionally, vaccines are made from weakened or killed viruses, or virus fragments. But producing large amounts of vaccine that way can take years, because such vaccines must be made in cells (SN: 7/7/20), which often aren’t easy to grow in large quantities.

Getting an early good look at the coronavirus’s genetic makeup created a shortcut. It let scientists quickly harness the virus’s genetic information to make copies of a crucial piece of SARS-CoV-2 that can be used as the basis for vaccines.

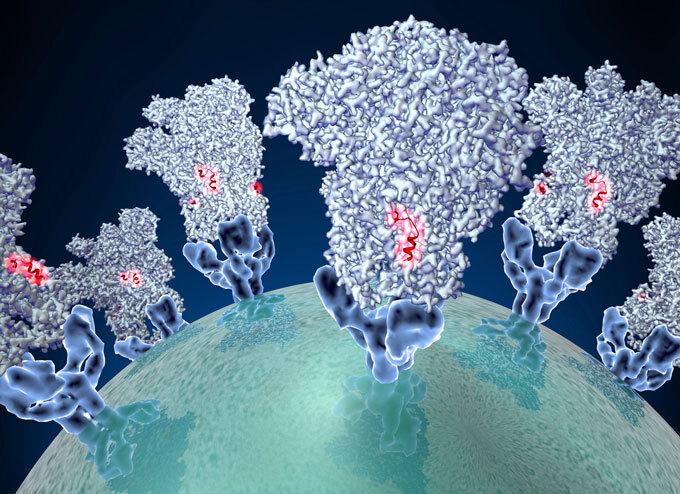

That piece is known as the spike protein. It studs the virus’s surface, forming its halo and allowing the virus to latch onto and enter human cells. Because the spike protein is on the outside of the virus, it’s also an easy target for antibodies to recognize.

Researchers have copied the SARS-CoV-2 version of instructions for making the spike protein into RNA or DNA, or synthesized the protein itself, in order to create vaccines of various types (see sidebar). Once the vaccine is delivered into the body, the immune system makes antibodies that recognize the virus and block it from getting into cells, either preventing infection or helping people avoid serious illness.

Using this approach, drugmakers have set speed records in devising vaccines and beginning clinical trials. FasterCures, which is part of the Milken Institute think tank, is tracking 179 vaccine candidates, most of which are still being tested in lab dishes and animals. But nearly 20 have already begun testing in people.

Going to trial

Some front-runners have emerged, leading the pack in a neck-and-neck race. Some have been propelled by an effort by the U.S. federal government, called Operation Warp Speed, which has picked a handful of vaccine candidates to fast-track.

First out of the starting gate was one developed by Moderna, a Cambridge, Mass.–based biotech company. It inoculated the first volunteer with its candidate vaccine on March 16, just 63 days after the virus’s genetic makeup was revealed. The company has since reported preliminary safety data, and some evidence that its vaccine stimulates the immune system to produce antibodies against the coronavirus (SN: 5/18/20).

That company and several others now have vaccines entering Phase III clinical trials. Moderna and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, in Bethesda, Md., will begin inoculating 30,000 volunteers with either the vaccine or a placebo in July to test the vaccine’s efficacy in large numbers of people.

Moderna’s vaccine requires two doses; a prime and a boost. That means “it will take 28 days to get any individual person vaccinated,” NIAID director Anthony Fauci said June 26 during a Milken Institute webinar. It will take “weeks and months” to give the full set of shots to all those people. Then it will take time to determine whether more people in the placebo group get COVID-19 than those in the vaccine group — a sign that the vaccine works. Those results could come in late fall or early winter.

NIAID launched a clinical trials network July 8 to recruit volunteers at sites across the United States for phase III testing of vaccines and antibodies to prevent COVID-19. Moderna’s vaccine will be the first in line for testing.

Some researchers propose accelerating clinical trials even further by trying controversial challenge trials, in which vaccinated volunteers are intentionally exposed to the coronavirus (SN: 5/27/20). None of those studies have gotten the green light yet.

Three other global drug and vaccine companies have announced plans to launch similarly sized trials this summer: Johnson & Johnson; AstraZeneca, working with the University of Oxford; and Pfizer Inc., which has teamed up with the German company BioNTech. Like Moderna, all are part of Operation Warp Speed, or will be joining it.

Eye on safety

Usually, Phase III trials are about determining efficacy. But the rush to get through earlier stages designed to make sure a drug doesn’t cause harm means that scientists also will be keeping a keen eye on safety, Fauci said. Researchers will be watching, in particular, for any suggestion that antibodies generated by the vaccine might enhance infection.

That can happen when antibodies stimulated by the vaccine don’t fully neutralize the virus and can aid it getting into cells and replicating, or because the vaccine alters immune cell responses in unhelpful ways. Vaccines against MERS and SARS coronaviruses made infections with the real virus worse in some animal studies.

Such enhanced infections are a worry for any unproven vaccine candidate, but some experimental vaccines in the works may be more concerning than others, says Peter Pitts, president of the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest, a nonprofit research and education organization headquartered in New York City.

For instance, China-based CanSino Biologics Inc. has developed a hybrid virus vaccine: It’s made by putting the coronavirus spike protein into a common cold virus called adenovirus 5. That virus can infect humans but has been altered so that it can no longer replicate.

In a small study, reported June 13 in the Lancet, CanSino’s vaccine triggered antibody production against the spike protein. But many volunteers already had preexisting antibodies to the adenovirus, raising concerns that that could weaken their response to the vaccine. A weakened response might make an infection worse when people encounter the real coronavirus, Pitts says.

That’s of particular concern because CanSino said in a June 29 statement to the Hong Kong stock exchange that its vaccine was approved by the Chinese government for temporary use by the Chinese military. That’s essentially turning soldiers into guinea pigs, Pitts says.

The type of antibodies stimulated by the vaccine will be important in determining whether the vaccine protects against disease or makes things worse, Yale University immunologists Akiko Iwasaki and Yexin Yang, warned April 21 in Nature Reviews Immunology. Some types of antibodies have been associated with more severe COVID-19.

And it will be important to monitor the ratio of neutralizing antibodies and non-neutralizing antibodies, as well as activity of other immune cells triggered by the vaccines, an international working group of scientists recommended in a conference report in the June 26 Vaccine.

Public health officials will also be tracking side effects closely. “As big as the vaccine trials may be, we can’t be sure that there aren’t rare side effects,” Anne Schuchat, principal deputy director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said June 29 during a question-and-answer session with the Journal of the American Medical Association. “That’s why even when we get enough to vaccinate large numbers, we’re going to need to be following it.”

In 1976 for instance, it turned out that Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare neurological condition in which the immune system attacks parts of the nervous system, was a rare side effect of the “swine flu” influenza vaccine. That didn’t become obvious until the vaccine had already been rolled out to 45 million people in the United States.

Measuring success

Early on, it was unclear whether scientists could devise a vaccine against the coronavirus at all. It’s now a question of when rather than if we’ll have a vaccine.

But some researchers have expressed concern that rushing clinical trials might lead federal regulators to approve a vaccine based on its ability to trigger antibody production alone. It’s still unclear how well antibodies protect against reinfection with the coronavirus and how long any such immunity may last (SN: 4/28/20). The measure of whether the vaccine works should be its ability to protect against illness, not antibody production, Fauci said.

“I really want to make sure that we don’t have a vaccine that’s distributed among the American people unless we know it’s safe and we know it is effective,” he said. “Not that we think it might be effective, but that we know it’s effective.”

So far though, companies are measuring success by the antibody. For instance, INOVIO, a biotechnology company based in Plymouth Meeting, Pa., announced June 30 that 94 percent of participants in a small safety trial made antibodies against the coronavirus. The data, delivered via news release like that from numerous other companies rushing to show progress, had not been peer-reviewed and other details about the company’s DNA-based vaccine were sparse.

Building trust

Despite still having much to prove, companies are gearing up manufacturing without knowing if their product will ever reach the market. By the end of the year, companies promise they can have hundreds of millions of doses. “We keep saying, ‘Are you sure?’ And they keep saying yes,” Fauci said. “That’s pretty impressive if they can do it.”

For instance, if everything goes right, a vaccine in testing now from Pfizer might be available as soon as October, Pfizer chairman and chief executive Albert Bourla said during the Milken Institute session. “If we are lucky, and the product works and we do not have significant bumps on our way to manufacturing,” he said, the company expects to be able to make 1 billion doses by early next year.

Pfizer released preliminary data on the safety of one of four vaccine candidates it is evaluating July 1 at medRxiv.org. In the small study of 45 people, no severe side effects were noted. Vaccination produced neutralizing antibodies at levels 1.8 to 2.8 times levels found in blood plasma from people who had recovered from COVID-19, researchers reported.

Novavax Inc., a Gaithersburg, Md.-based biotechnology company, announced July 7 that it was being award $1.6 billion from Operation Warp Speed to conduct phase III trials and to deliver 100 million doses of its vaccine as early as the end of the year.

If manufacturers can deliver a vaccine as promised, there could be another big hurdle: There’s no guarantee people will line up for shots. About a quarter of Americans said in recent polls that they would “definitely” or “probably not” get a coronavirus vaccine if one were available. “That’s a pending public health crisis,” Pitts says.

Krofah agrees. “We need to think about the post-pandemic world in the midst of all of this,” she says. “We need to … start building that public trust now.” Tackling issues of vaccine hesitancy shouldn’t be left until a vaccine is available, she says.

Whether with vaccines or treatments, “we need to expedite, but not rush,” Pitts says. “There’s a perception that therapeutics or vaccines will be approved willy-nilly because of politics, and that’s a dangerous misperception.” The FDA laid out guidelines, including an accelerated approval process, on June 30 that should ensure any approved vaccines work, he says.

There is good news for those who are eagerly awaiting vaccines, Krofah and Pitts say: There won’t be just one winner in the race. Instead, there may be multiple options to choose from. That’s not a luxury; it may be a necessity. Multiple vaccines may be needed to protect different segments of the population, Krofah says. For instance, elderly people may need a vaccine that prods the immune system harder to make antibodies, and children may need different vaccines than adults do.

What’s more, long-term investments in development will be needed so that vaccines can be altered if the virus mutates. “We need to stay the front and not declare victory once a vaccine has been approved for emergency use,” she says.

For now, vaccine makers are moving both as quickly and as carefully as possible, Bourla said. “I am aware that right now that billions of people, millions of businesses, hundreds of governments are investing their hope for a solution in a handful of pharma companies.”

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.